I would like to do something that Dominicans typically don’t do: exhort. I’d like to exhort you to read Pope Benedict’s new book, Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives. This is the third of the Pope’s books on the life of Christ to be released since 2007. In the first volume, he described the preaching and public ministry of Christ. In the second, he meditated on the events of Holy Week and the Paschal Mystery. In the most recent volume, he takes us back to the beginning of the Gospels, treating the birth and early life of Christ.

The Pope does not refer to his latest book as a “third volume”, but rather as an “antechamber” to the first two volumes. Thus, if you have not yet read either of these, this latest release is a particularly attractive way to begin tapping into Pope Benedict’s profound insights and enjoying the fruit of his own “personal search for the face of Jesus.” The third book is also apropos of the present liturgical season, when the Church focuses her contemplative gaze on the narratives of Christ’s early life. Finally, you need not be a theologian or a scholar to read these books with ease and to profit from them.

So, if you’ve wanted to read Jesus of Nazareth: The Infancy Narratives but, for whatever reason, haven’t done so, this post is here to give you a friendly nudge. Consider yourself exhorted.

Now that I’m done exhorting, I can move on to the more typically Dominican task of explaining. I must confess, I’ve only read the Pope’s new book once, and therefore I cannot come close to offering an adequate evaluation. I’m also no theologian or specialist in New Testament Studies or Christology. But, as C.S. Lewis once observed, schoolboys often teach each other things faster than any instructor could, because they explain simply what is necessary. In this way, from one casual reader of Pope Benedict to another, I hope to offer you some helpful remarks on the Pope’s new book.

To me, its most distinctive trait is that, in it, Benedict offers principles but no conclusion. He leads you to the waters of divine wisdom, which flow from the pages of Scripture, but it’s up to you to drink. In each chapter, he situates the scriptural narratives within their proper historical context, and he offers a range of scholarly opinions, as well as a history of interpretation. Then, after all of what appears to be preparation for a lengthy spiritual excursus, he concludes with only a few sentences (or at most a paragraph) of reflection.

For example, after discussing King Herod’s fear of the kingship of Christ, he leaves us with this: “God disturbs our comfortable day-to-day existence. Jesus’ kingship goes hand in hand with his Passion.” You could meditate on this for a whole retreat! The Pope could easily continue and draw out all of the story’s deep spiritual meaning, but instead he stops and goes on to consider the next item. This style punctuates the entire work.

In one way, this style can be a little frustrating. The Pope leads us through the more scholarly material only to leave us with a tiny spiritual teaser at the end. In reality, however, there is a great deal of merit in this method. Pope Benedict does the heavy lifting for us and then leaves us free to walk, unencumbered, into the mystery of Christ’s early life. Not only does he refrain from forcing our soul’s horses to drink; he even allows us to go beyond the visible water. The brief spiritual reflections that punctuate the work are not annoying teasers, leaving the reader empty. Rather, they function as a sort of on-ramp to meditation and contemplation.

If Benedict were to offer an extended spiritual reflection in every section, not only would the book be much longer, but the reader might also more easily miss the point. By pointing us to the mysteries, rather than forcing them upon us, the Pope allows them to shine with their own true brilliance and splendor. Furthermore, because there is no attempt to offer an exhaustive treatment, the events of Christ’s early life are more easily perceived precisely as mysteries.

In the Christmas season, the Church gazes upon the principle of salvation: Jesus Christ, God made man for the salvation of the world. While it is true that the Church considers Christ’s birth in light of his passion, death, and resurrection, the Christmas season is more directly concerned with the infant Savior. True, his manger will be traded for a Cross, but for now we allow our gaze to rest in Bethlehem. We know the conclusion, but for a while we rest in the presence of the principle—the human beginnings of the One who was in principio.

This applies to us personally as well. We are not sure how the grace of Christ will shape our lives. The Word has been made flesh, but my salvation and yours have yet to be—pardon the pun—completely fleshed out. The virgin Mother of God is our model for the task at hand: to gaze in faith on the face of the Christ child. Even now, in the darkness of the “not yet,” we rest in the peace of salvation.

✠

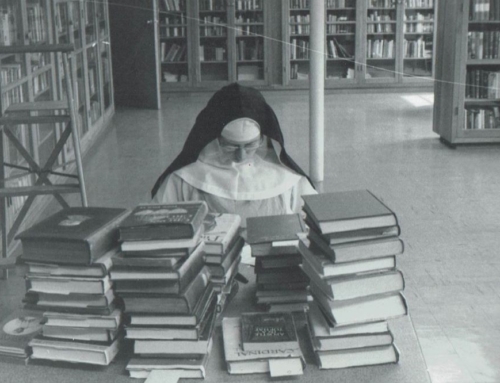

Image: Codex of Predis (1476)