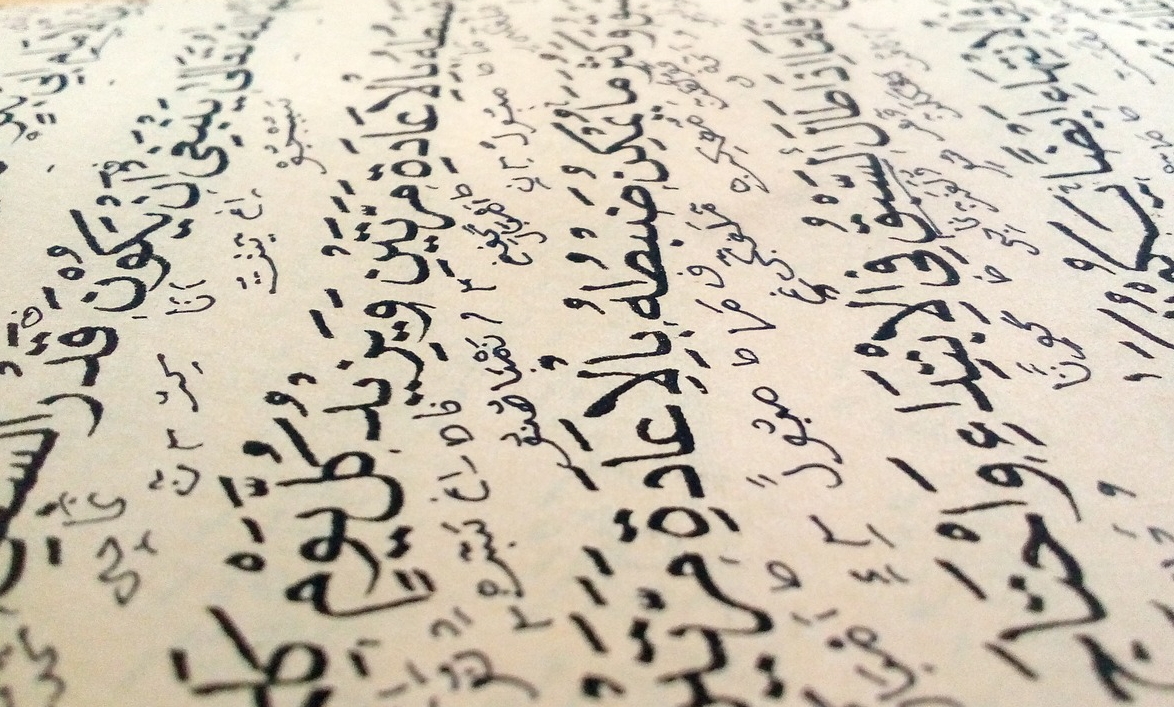

Christians may be surprised to learn that the Islamic holy book—the Qur’an, written in the seventh century A.D.—portrays Jesus as a major prophet. In fact, the name “Jesus” appears in the Qur’an about thirty-five times. But the reverence for Jesus in the Qur’an does not amount to the worship that Christians render. Given the importance of the disagreement, it’s worth examining some of the Qur’anic texts that mention Jesus.

The Qur’an affirms the virgin birth (19.16–22) and claims that Mary was rebuked when she brought Jesus home to her people. In defense, Mary appealed to her baby, but the people replied, “How can we talk to one who is a child in the cradle?” (19.29) Then, the babe himself opened his mouth:

I am indeed a servant of Allah: he hath given me Revelation and made me a prophet: . . . He hath made me kind to my mother, and not overbearing or unblest; So Peace is on me the day I was born, the day that I die, and the day that I shall be raised up to life again! (19.30–33)

That last exclamation notwithstanding, the Qur’an is traditionally interpreted to deny both the crucifixion of Jesus and his personal resurrection (19.15; 4.157). The infant prophet says nothing about the manner of his death, and his resurrection is read as merely one among many at the end of time. On the contrary is St. Peter’s sermon after Pentecost: “this Jesus . . . you crucified and killed . . . But God raised him up” (Acts 2:23–24).

The Qur’anic oration of the baby Jesus has an analogue in the non-canonical Arabic Infancy Gospel, written in the fifth or sixth century A.D. There the infant speaks not to defend his mother but simply to inform her: “I am Jesus, the Son of God, the Word, whom thou hast brought forth . . . and my Father has sent me for the salvation of the world.” Of course, the first-century canonical Gospels (of Matthew, Mark, Luke, and John) say nothing about the baby Jesus giving a speech.

As for the works of Jesus, the Qur’an employs this concise triptych:

I [Jesus] have come to you, with a sign from your Lord, in that I make for you out of clay, as it were, the figure of a bird, and breathe into it, and it becomes a bird by Allah’s leave; and I heal those born blind, and the lepers, and I bring the dead into life by Allah’s leave . . . [and I have come] to attest to the Torah which was before me, and to make lawful to you part of what was forbidden to you. (3.49–50)

Wonders, healing, and teaching. This threefold description approaches the account of the canonical Gospels, except for that bit about the bird—which story, however, is not without precedent. The non-canonical Infancy Gospel of Thomas has the boy Jesus enliven not only one clay bird but twelve. And the Arabic Infancy Gospel depicts Jesus outdoing his playmates by sculpting a veritable zoo of figurines before bringing them to life. We read that the other boys’ parents were not amused: “My sons, . . . he is a wizard . . . do not play with him again.” The four canonical Gospels are more sober. St. Luke tells us that at the age of twelve Jesus amazed his audience at the Temple, but the evangelist says nothing about the seven-year-old Jesus bidding his toys take flight.

Historians speculate that Christians used such stories to argue for Jesus’ divinity. Notice, however, the Qur’anic caveat: “by Allah’s leave.” Not by his own power did Jesus give sight to the blind, but “by Allah’s leave.” It was “by Allah’s leave” that he cured lepers and raised the dead. The denial of Jesus’ divinity is clearest in surah (chapter) four:

The Messiah, Jesus the son of Mary, was a Messenger of Allah and His Word, which He bestowed on Mary and a spirit created by Him; so believe in Allah and His Messengers. Say not: ‘Three.’ Cease! It is better for you. For Allah is one God; Glorified is He above having a son. (4.171)

Such texts are crafted to counter the fundamental Christian confession: “Jesus Christ is Lord” (Phil 2:11). In Christian doctrine, the Incarnation is closely related to knowledge of the Trinity. Unless God became man in Christ, there is little reason to wonder about personal distinctions in God.

People sometimes seem to think that Islam takes nothing away from Christianity. Since the Qur’an speaks of Jesus and succeeds Christianity by centuries, it is assumed that Islam can only add to our knowledge of God. In fact, we stand to lose a great deal—nothing less than the historical Jesus, whom Christians believe is literally divine. Nothing less than the inner life of God—Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.