There have been two basic impulses in the history of Christianity: to go into the wilderness, fleeing the city to prepare the way of the Lord, and to go into the city, letting the light of Christ shine in the midst of the difficulties and delights of everyday life. Jesus, of course, did both—he went into the desert after his baptism by John, and on countless occasions retired from the crowds to pray—and yet he continually returned to the Holy City, even when this meant risking his life.

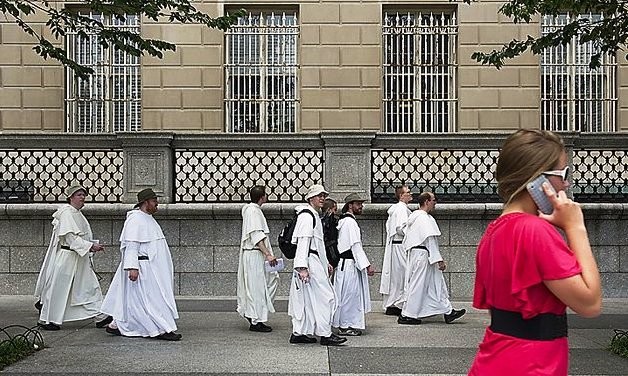

Throughout the centuries, some Christians have received the grace to imitate Christ in one or the other of these two locations. The great Benedictine tradition has tended towards the evangelization of the wilderness, preaching the Gospel to every creature, including the cows that are milked and the grapes that are pressed. Other impulses, such as the mendicant orders, have tended to focus their efforts on the cities, for where sin (and universities) abound, Franciscans and Dominicans abound all the more. In each case, it is not a matter of one approach or location being better or worse in itself—each present authentic paths for following the poor, humble and cross-bearing Christ.

Those who attempt to evangelize within the city, however, are compelled to deal with the temptation of becoming enmeshed in the frantic pace which can dominate their environment. Within all their activity, as noble as it may be, it is necessary to enter into the rest of the Lord “in whom we live, and move, and have our being.” In the midst of activity, we must develop a contemplative spirit that can understand the presence of the Lord in both the earthquakes of the subway and the thin, small voice of the ersatz monk selling trinkets in Times Square. As Pope Francis recently wrote,

We need to look at our cities with a contemplative gaze, a gaze of faith which sees God dwelling in their homes, in their streets and squares. God’s presence accompanies the sincere efforts of individuals and groups to find encouragement and meaning in their lives. He dwells among them, fostering solidarity, fraternity, and the desire for goodness, truth and justice. This presence must not be contrived but found, uncovered. (Evangelii gaudium 71).

In this gaze of faith, we imitate the Lord Jesus who, when he approached the city, gazed at it—and wept over it (cf. Lk 19:41). It is not that we are set above our fellow city dwellers, for we too need to be gathered by Jesus like a hen gathers her brood (cf. Lk 13:34). Our weeping is often more like that of Peter, who after the Lord turned and looked at him, remembered the word of the Lord: “Before a rooster crows today, you will deny Me three times” (Lk 22:61-62). Like those with whom we dwell, we are sinners—and yet are sinners whom the Lord has looked upon. This gaze of Jesus is one that heals as it wounds. This means that despite our sin and imperfection, we can still offer a witness to the hope that is in us.

Christianity is not a religion for those who have already saved themselves, whether they carry out this task in the country or the city. Jesus Christ came to save sinners, for of ourselves we can do nothing. And yet, whether we bumble about in a bustling metropolis or toil with thirsty brow in the midst of the countryside, through the grace of God we can still follow Christ, who is the Way, the Truth, and the Life.

✠

Image: Dominicans in Washington, D.C.