After years of interrogation at the hands of the Soviet secret police, the American Jesuit Walter Ciszek reached a breaking point. He had been falsely accused of spying for the Vatican and was subjected to isolation and near starvation. As he records in his autobiographical account He Leadeth Me, under this strain his prayer life and mental stability both collapsed in a moment of despair: “I knew that I had gone beyond all bounds, had crossed over the brink into a fit of blackness I had never known before.” The cause of this crisis? He had always conceived of his “role—man’s role—in the divine economy as an active one,” but now, brought to destitution, he hadn’t the strength to go on. Thus for “one sickening split second,” he gave up on his life and on his salvation.

He came out of this experience only after being stripped of all trust in his own strength: “I realized I had been trying to do something with my own will and intellect that was at once too much and mostly all wrong.” He discovered that he had to see that every action, every impulse, was a moment for cooperation with the directive love of God.

While Ciszek came to understand what it meant to rely on God’s grace through extraordinary suffering, it’s something we all have to learn. And for all of us, it involves suffering—primarily, the suffering of dying to self. How do we let go of that trust in ourselves that makes us so defensive when challenged, so worried when we’re uncertain about the future, and so frustrated when things don’t go according to our plans? So much of our mental and spiritual energy goes into protecting that center of false self-reliance that its removal seems impossible for us. And, for man, it is impossible.

The psalmist tells God, “It was good for me to be afflicted / to learn your will.” That’s fairly easy to say in a moment of contentment, but if someone told that to me during the miseries of the stomach flu, let alone in a Soviet prison camp, I’d find it much harder to believe. But notice that the psalmist says it was good—he’s reflecting on the past. He didn’t necessarily see or appreciate the point of afflictions while they happened, but in retrospect he can begin to see why God had allowed the difficulties in his life. His understanding came from a habit of reflecting about what had happened to him, what God had allowed.

I’m reminded of the title character in Marilynne Robinson’s novel Lila. She spends much of the book musing: “I just been wondering lately why things happen the way they do.” It sounds like a simple question, but the very phrasing of it implies a deep insight—things happen. Like the psalmist and Ciszek, Lila, too, had suffered. She had known what it was to be powerless. She had lived a childhood that would have been disorienting and traumatizing to the steadiest disposition. If someone told her she was the maker of her own destiny, it would have sounded a farce to her. As a result, she lives a posture towards her own life that is one of wonder—“I just been wondering”—even if it’s a wonder that is often confused and frightened.

Things happen to us and we don’t know why. We don’t create our lives; we haven’t chosen many of their events. We both participate in the story of our lives and observe them. As we live, and suffer, we have the opportunity again and again to wonder and ponder why things happen the way they do. Over time, we can hope with Ciszek “to see [God’s] will in all things, … to accept every situation and circumstance and let oneself be borne along in perfect confidence and trust.”

✠

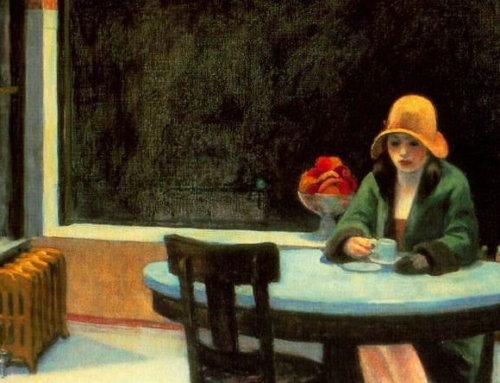

Image: Mary Magdalene weeping. (Image by user Pethrus, CC BY-SA 3.0, cropped.)