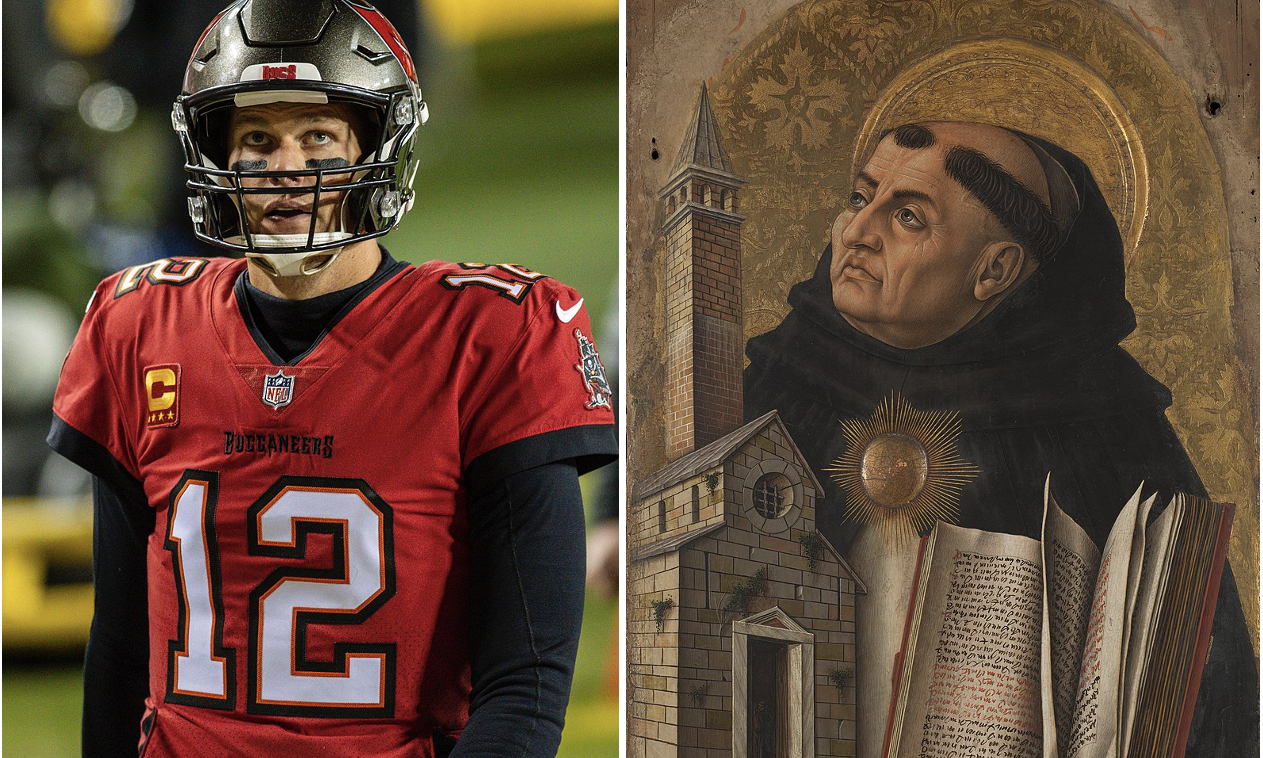

Do Saint Thomas Aquinas and Tom Brady have anything in common? Besides sharing a first name and Catholic baptism and being GOATs in their respective fields—sacred theology and professional football—it might seem as if they didn’t. One was a medieval friar and masterful theologian; the other is a modern football genius and global icon.

But one interview with the now seven-time Super Bowl Champion—given back in 2005, after his third championship—places the two Thomases in agreement on something important. Reflecting on his football success and the unforeseen baggage of stardom, Brady remarked:

Why do I have three Super Bowl rings and still think there’s something greater out there for me? I mean, maybe a lot of people would say, “hey man, this is what it is—I’ve reached my goal, my dream, my life is”—me, I think, “God, it’s gotta be more than this.” I mean, this isn’t—this can’t be what it’s all cracked up to be. I mean, I’ve done it. I’m 27. And what else is there for me?

To Touchdown Thomas’s candid and earnest words, the Dominican Thomas offers a profound explanation as to why Super Bowl wins and their accompanying celebrity cannot possibly be what they’re “all cracked up to be.”

In his classic “Treatise on Happiness” in the Summa Theologiae, St. Thomas ponders eight types of goods commonly considered to be man’s final end (i.e., the cause of our enduring happiness). He begins with four exterior goods: wealth (e.g., money or material goods), honors (awards), fame (praise or repute), and power (influence or authority). Then, he considers three interior goods: bodily goods (appearance, strength, health), bodily pleasures (food, drink, sex), and goods of the soul (knowledge, friendships, artistic excellence, etc.).

St. Thomas notes that each of these seven—while good—is finite, contingent, and particular. And because every human person by nature possesses a rational appetite (a will)—giving him an innate desire for universal goodness—no particular, created good can ultimately satisfy. Thus, St. Thomas proposes an eighth good that does ultimately satisfy: God, who by his infinite, uncreated being and universal goodness both causes every created good and super-exceeds them all beyond measure.

Touchdown Thomas bears witness to this. He knows that he could always earn another dollar, win another Super Bowl, be featured on another cover, captain another team, play another year, or celebrate another championship parade. These exemplify the first six of the goods on Aquinas’s list—about which Brady admits, “it’s gotta be more than.”

What, then, draws Brady back for a 22nd season? He answers, “it’s really just the love of football,” which, as a kind of human excellence, is a good of the soul—the seventh good in Aquinas’s list. Over the course of two decades, Brady has become a football master. Though never heralded as a natural athlete, Brady distinguishes himself as a “field general” by stellar mechanics and, especially, his unparalleled football knowledge. He knows inside and out football’s universal schematic principles, which enables him to make line-of-scrimmage reads and execute passes that other quarterbacks could not fathom. Indeed, Brady’s depth of football knowledge actually causes him to enjoy the game more, for he understands more profoundly and thereby delights more intensely in his team’s success. Which is also why he so hungers for it.

And yet, for all of this, because football is a particular good, Brady’s will cannot finally rest in it. Nor can his will—or any human will—rest in any other particular goods of the soul, like marriage and family, or noble hobbies, or “balance” in life. This is a matter not of taste or preference—as if we need only find the right particular good—but of the very structure of our will and its innate desire for universal, infinite goodness, in which every finite good is a mere participation. “In God alone is my soul at rest” (Ps 62:1).

Touchdown Thomas’s 2005 instincts were certainly correct. But is he a Thomist? Well, when prompted to answer what that “more than this” might be, he exclaimed, “I wish I knew!” A decade later, Brady was abashed at the “narrow perspective” he offered in that interview. (Apparently, he was mailed a “litany of Bibles” in its wake.) Though ten years older, he again balked when pressed: “I think we’re into everything . . . I don’t know what I believe. I think there’s a belief system, I’m just not sure what it is.”

So how might the Dominican Thomas counsel his modern namesake in his continual pursuit of the contingent? Return to your own words in 2005. The “more than this” is the One you yourself invoked:

GOD.

✠

Photo (Tom Brady) from All-Pro Reels (CC BY-SA 2.0)

Image (St. Thomas) by Carlo Crivelli, from Wikimedia Commons