One of the most influential and now forgotten historians of the 19th century was the Austrian Dominican Heinrich Denifle. Despite having many administrative responsibilities, Fr. Denifle found time to pore over thousands of medieval manuscripts, making significant contributions to the study of medieval mysticism, the rise of universities, the Hundred Years War, and the life of Martin Luther. During his lifetime, his work was lauded by Catholic, Protestant, and secular scholars throughout Europe.

In his later years, Fr. Denifle examined the general decline in observance among the clergy in the late Middle Ages, as well as the not infrequent counter-examples of heroically virtuous clerics. During the 14th and 15th centuries, Europe endured the threefold calamity of war, famine, and plague; Europe’s population would not fully recover until the industrial revolution. Death claimed the wicked and the pious alike, and the Church herself was rent with schism. Moreover, the prevailing intellectual trend of the age—Nominalism—posited an utterly arbitrary and terrifyingly vengeful God. These factors led many in the late Middle Ages—even priests and religious—to adopt either an extreme asceticism or a nihilistic hedonism. Fr. Denifle observed that the curious thing about many lax priests was that they continued to know right from wrong. Their error lay, rather, in thinking that they could not help but sin when confronted with temptation.

Sound familiar? Many of our contemporaries still recognize the wrongness of sins like overeating, adultery, slander, and embezzlement. Yet so often we exonerate ourselves by protesting our own lack of freedom: “I just couldn’t help myself.” Our society is quick to explain disordered actions by pointing to psychological or biological causes, whether traumatic experiences, psychological disorders, or simply being born a particular way. In attempting to alleviate moral guilt, this modern tendency strips the human agent of liberty, reducing him merely to reacting to stimuli rather than making free and creative choices. Yet the Scriptures are quite clear that men—in general—retain moral responsibility for their deeds. While psychological and physiological disorders may influence human behavior negatively, they are not the only cause of disordered actions.

As St. Thomas Aquinas explains, the possibility for sin rests primarily in the freedom of our created natures. As creatures, we are finite and, therefore, defectable, able to go astray by not loving what we ought as we ought. Moreover, due to the stain of original sin, fallen man is less inclined to good actions. There is ignorance in the intellect and malice in the will, by which we love lesser goods more than we ought. Even our sense appetite is disordered by concupiscence and weakness: we are too desirous of sensual goods, and we are unwilling to strive after difficult goods. Thus, our senses and emotions can often overmaster our impaired intellects and wills, leading us to act unreasonably.

Yet original sin did not corrupt human nature entirely, as though Adam and Eve were transformed into some other sort of creature. Man remains created in the image and likeness of God, a rational creature possessed of intellect, will, and free choice. No matter how disinclined towards virtue he may be in his sinfulness, he retains the seeds of virtue, for the inclinations towards truth and goodness—the goals of virtuous actions—are inscribed in the very nature of his intellect and will. Moreover, the baser powers remain fundamentally subordinated to the higher, yearning to be directed well by free choices. Sin does not destroy our liberty, it merely makes it more difficult to exercise it—to act as we know we ought (see Rom 7:19). Yet God’s grace is capable of penetrating the depths of our fallen nature, healing and elevating it interiorly. Therefore, let us neither despair of ever being able to resist temptation nor protest our inability to act according to right reason. Rather, let us remember that our nature has not been utterly denuded of its freedom, and let us beseech God’s aid in exercising our liberty well despite our woundedness, remembering his teaching, “My grace is sufficient for you, for my power is made perfect in weakness” (2 Cor 12:9).

✠

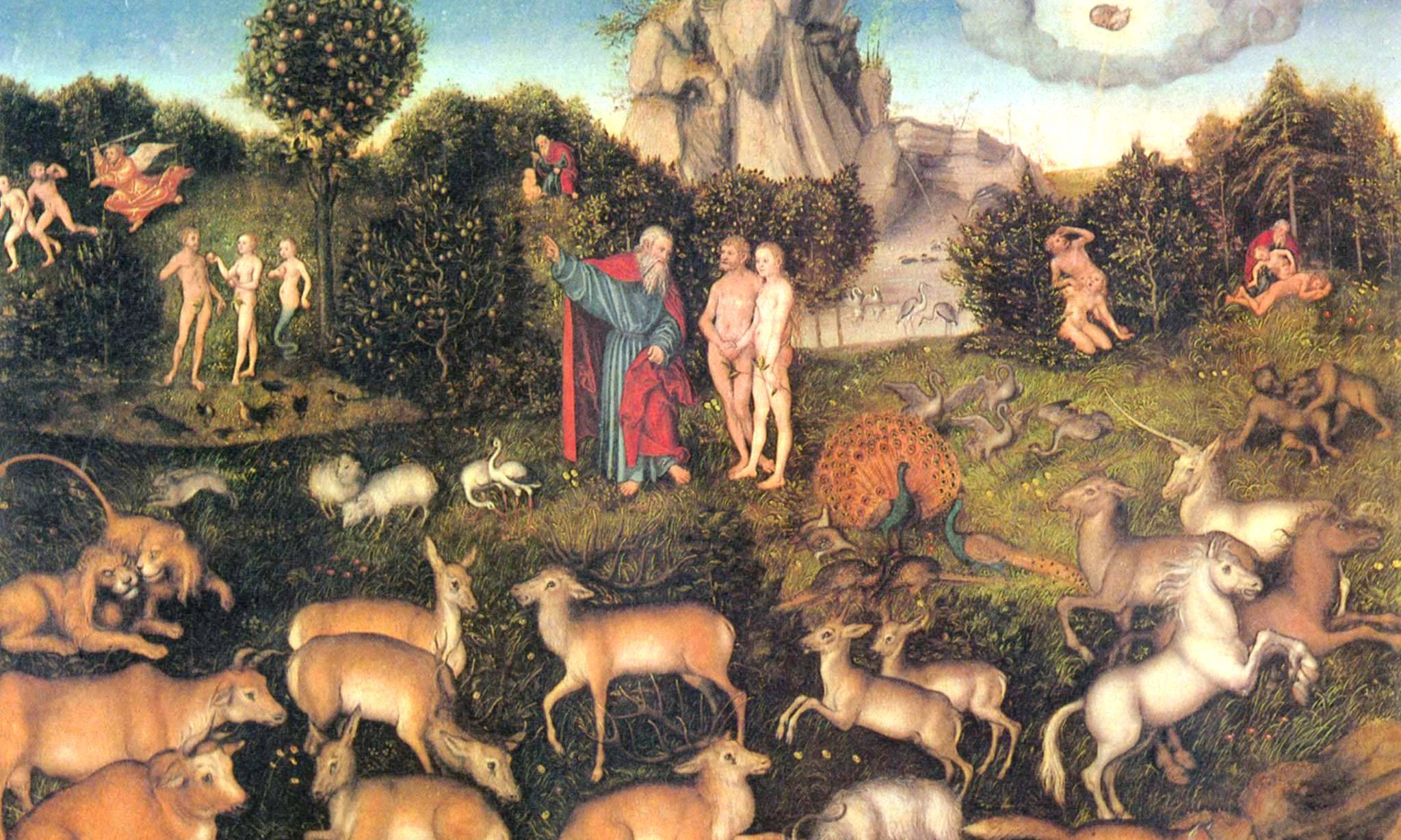

Image: Lucas Cranach, The Garden of Eden