Aquinas and the Fathers: Boethius

This post is part of a series on Saint Thomas Aquinas’s reception of the wisdom of the ancient Church. To learn more about the inspiration behind the series, you can read its introduction here. To read more posts in the series, click here.

The all-perfect, ever-living God, “with whom there is no variation or shadow due to change” (Jas 1:17), has revealed himself to us. Faith leads us beyond natural knowledge to know personally the eternal “I AM” (Exod 3:14). The prophet Malachi saw that the immutability of God’s goodness was the one hope of his rebellious people: “I, the Lord, do not change; therefore you, O sons of Jacob, are not consumed” (Mal 3:6). We can rely on God’s mercy because of his perfect eternity. When Saint Thomas considers this scriptural mystery, he turns to the work of a brilliant patristic predecessor: Saint Boethius.

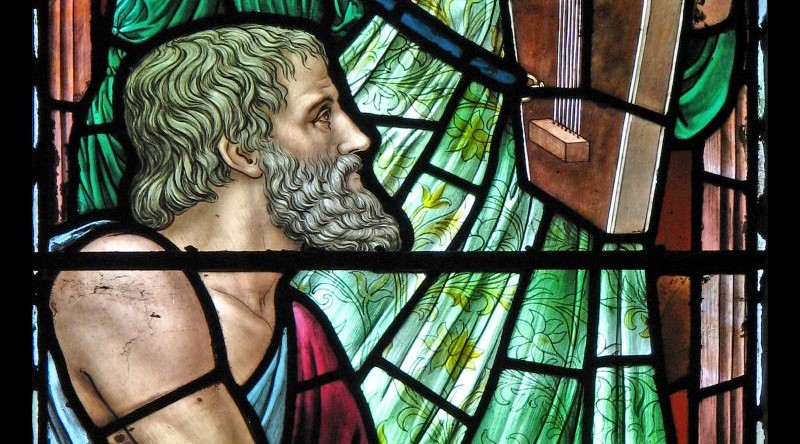

Boethius, a Roman senator, lived about a century after Saint Augustine. He found himself heir to a vast Greek and Latin philosophical tradition, and worked to preserve and pass on this patrimony to future ages. As a Christian theologian, he also composed penetrating works on Christ and the Trinity. This work was not merely an academic exercise: Boethius’s Ostrogothic overlords, including King Theoderic, were committed Arian heretics. Theoderic had Boethius executed (c. 524) under suspicion of his sympathizing with the Catholic Byzantine emperor, and the Church now honors Boethius as a saint and martyr.

Boethius’s most famous work, On the Consolation of Philosophy, shows only glimpses of the man’s deep Christian faith. Writing while awaiting his impending death, Boethius chose to gather together the wisdom of Plato, Aristotle, and many other pagan thinkers, as personified by Lady Philosophy. Gradually, this patient teacher reminds him that worldly goods do not suffice for human happiness, that all of them eventually pass, and that they can be lost in an instant. Philosophy points him and us to higher things: to the life of virtue and ultimately to God, the highest good, and his eternal providence.

Aquinas’s theological reflection on God as unchanging and eternal begins with the inspired text of Malachi (ST I, q. 9, a. 1). As a theologian, Aquinas begins not with human wisdom but with Scripture and the articles of the faith. To think through this revealed mystery more fully, however, he turns to the Consolation‘s climax, where Boethius concludes that eternity is “the simultaneously-whole and perfect possession of interminable life” (ST I, q. 10, a. 1). God’s eternity is an eternal now. He has no beginning or end and, more radically, there is no temporal succession in him, no hint of before and after. The Blessed Trinity’s unchanging love is an eternal blaze, without any possibility of growing cold. God created time and mercifully saved us in the fullness of time (Gal 4:4). But his mercy is rooted in his eternal nature, which cannot cease to be love itself.

Aquinas thus seamlessly adopts a philosophical definition of eternity from Boethius in order to further our theological understanding of God. Yet, some could object: why does he turn to philosophy at all? Aquinas would answer that the Christian is a lover of truth, wherever it is found. And in his study of Boethius, Aquinas saw this early Christian author championing the goodness of the human intellect and its ability to know the truth about God. The Church’s tradition, to which the Fathers bear witness, will always embrace the harmony of faith and reason.

This series has explored the ways Aquinas relied upon the Church Fathers. Their writings enjoy a privileged role, below Sacred Scripture, as proper authorities in sacred doctrine. But Saint Thomas also inherited a profound respect for philosophy from his patristic predecessors, including Boethius. Perhaps we wonder if we should dilute the pure wine of faith with the watery works of philosophy. Aquinas responds, commenting on another text from Boethius, that “those who use philosophical doctrines in sacra doctrina in such a way as to subject them to the service of faith, do not mix water with wine, but change water into wine” (Comm. De trin. q. 2, a. 3, ad 5).

All truth comes from God, who, because he is truly eternal, has a mercy that endures forever (Ps 136). By drawing upon the wisdom of those who have come before, whether that wisdom be from the realm of theology or philosophy, the Catholic theologian can know and love more deeply our unchanging and merciful God.

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)