This is part of a series entitled, “The Reason for Our Hope.” Read the series introduction here. To see other posts in the series, click here.

What does Hope look like? Is it a spring landscape untouched by fear and death? Is it a Romantic conquest of life’s sufferings? If we picture Hope, and if we’re being honest, it looks like the cross—a stumbling block and foolishness. But for one of the 20th century’s most controversial artists, the hope of the cross was a lasting inspiration.

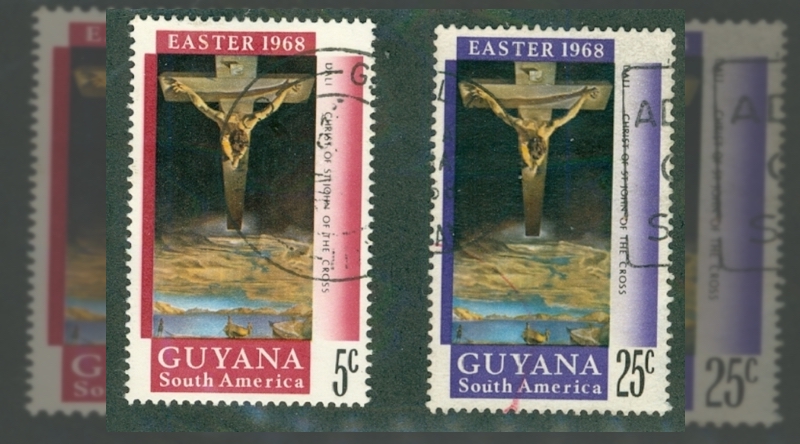

Salvador Dali is best known for his talents of melting clocks and defying gravity, but the final stage of the surrealist painter’s career was a hope-filled turn towards the sacred, in an effort “to save modern art from chaos” (LA Times archives). He presented an image of the Madonna and Child to Pope Pius XII and depicted an ephemeral Last Supper. But among his Catholic works the most beloved and most maligned is the Christ of Saint John of the Cross:

Fig. 1: Salvador Dali, Christ of Saint John of the Cross †

© CSG CIC Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections

Since its release Dali’s Christ has faced critical defaming and even physical defacing. Despite its dream-like composition, the public rejected the painting as too classical. And the critics didn’t know how right they were. Dali’s inspiration went far deeper than a confused dream or his typical metaphysical musings. He borrowed the extreme angle and mystical approach from the writings and sketches of the Carmelite contemplative Saint John of the Cross. Following a vision the 16th-century mystic sketched unique outlines of Christ’s crucifixion:

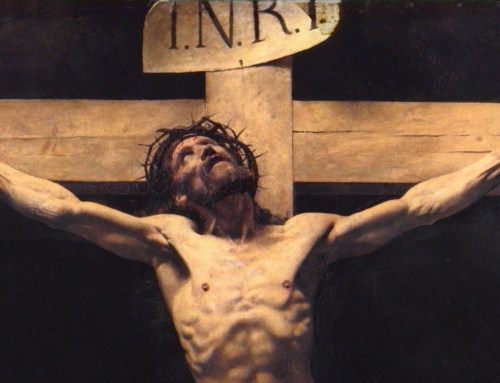

Fig. 2: John of the Cross, Crucifixion Sketch

Notice the same view from above. John of the Cross appears to be giving us a God’s eye view of the crucifixion. But what inspired John’s sketch goes deeper. He wanted to portray the perspective of a dying man venerating the cross receiving last rites. John of the Cross envisions the redemption of suffering—the final image of Hope of a man who had nothing left in the world. For John of the Cross, indeed for the Christian, the dying man’s perspective is one of Hope.

If Hope doesn’t ignore life’s sufferings, what does it do? Hope redeems them. Hope embraces the crosses of life—regrets, failures, betrayals, heartaches, whatever they may be—and gazes on them as God gazes on the cross. We are born into a valley of tears, and none of us pass through without suffering. We all suffer a sickness unto death, but through our redemption, our sickness has become the very path to new life. For Saint Paul, suffering was not only redeemable, but it was also a cause for rejoicing:

We rejoice in our sufferings, knowing that suffering produces endurance, and endurance produces character, and character produces hope, and hope does not disappoint (Rom 5:3–5).

We rejoice in our sufferings, not because they are good, not because we can exchange hardship for well-being, but because they fix our gaze. Our suffering, redeemed by the virtue of Hope, teaches us to loosen our grip on the world, and cling to Christ, the reason for our Hope.

Underlying John of the Cross’s original sketch is his insight that “we receive from God only according to the measure of our hope.” It is precisely when life seems most hopeless that we understand the divine meaning of the cross. It’s in that privileged moment of worldly hopelessness that we share the Father’s gaze. As God the Father looks on the suffering of God the Son in love, we look to Christ in our need, who fills our suffering with his presence. In our need we share the Father’s gaze, looking not to the cross but through it.

Dali paints a God’s eye view of Hope, in which the leading lines of Christ’s composition draw the viewer through the cross to life’s other shore. Dali superimposed the cross upon the shores of the sea, a locale that bookends Christ’s ministry. It was here that he called his disciples. It was on the sea that Christ calmed storms and walked on the waters on the way to his cross. It was to the shores of Galilee that the risen Christ returned to meet those who fled his passion. We reach the shores of Charity, and the abiding presence of God and the source of our longing, but only through the cross. Jesus Christ, who alone could truly gaze on the Father, felt the piercing of nails. In our Hope we share in Christ’s sufferings, whose suffering lets us understand our own.

Hope’s gaze is not a surreal view that distorts and exaggerates reality. Rather, Hope is a God’s-eye view. It is the strength to see all of reality, ignoring none of it, embracing all of it, all through the Father’s own wisdom and love. But Hope’s bold demand requires the divine help of clinging to Christ. Dali’s own life and death are a testimony to Hope. He lived as a self-professed “Catholic without faith,” yet he died having received the last rites. He died face-to-face with John’s own rendition of the cross, and face-to-face with the reason for his Hope. As we face the hardships that both threaten and justify our hope we turn to the same inspiration. We ask the saints who walk by sight to lend us their gaze, to share in the loving gaze between the Father and Son, and to help us understand our suffering through a God’s eye view.

✠

Image: Christ of St. John of the Cross, Guyana 1968 – 25c

†Image used with the gracious permission of the Glasgow Museums and Libraries Collections.