The fifth in a series considering Jane Austen in light of Aristotle and Thomas Aquinas.

Above all other blessings Oh! God, for ourselves, and our fellow-creatures, we implore Thee to quicken our sense of thy Mercy in the redemption of the World, of the Value of that Holy Religion in which we have been brought up, that we may not by our own neglect, throw away the salvation thou hast given us, nor be Christians only in name.

—from Jane Austen’s Prayers

One of the characteristic aspects of all of Austen’s novels is that they end in happy marriages for the heroines. Several modern literary critics have wondered at the motivation behind this feature of her novels, given that Austen herself never married. Is it the case that she was vicariously living through her characters? Was she simply giving the readers what she knew they wanted? Or is there perhaps something more profound motivating her use of the marriage construct? Some critics have speculated as much. For example, one can find traces of a critique of the French Revolution in Pride and Prejudice, complete with an ‘English’ solution: a marriage between the middle and upper classes.

Here, I would like to offer quite a different allegorical interpretation of the marriage plot as used by Austen. It is easy to consider the marriages simply as the reward for the virtuous efforts of her heroines, especially considering that each one is brought about through a Deus ex machina. They all have struggled through the challenges of life and have come out on the other side as women possessing and growing in virtue. From this perspective, then, marriage is the end towards which the virtuous lives of her heroines are directed. Turning Henry Crawford’s allusion to Milton on its head, for Austen’s heroines, marriage is heaven’s last best gift.

Such a notion of a final end that rewards all the trials of a virtuous life is by no means foreign to virtue ethics. In the Nicomachean Ethics, Aristotle identifies the end of the virtuous life as contemplation; it is this state of rest to which every act of virtue is directed and in which true happiness consists. Like true friendship, contemplation is sought for its own sake; it is the most self-sustaining form of life and the most pleasant of activities. Building upon Aristotle, St. Thomas Aquinas identifies the final end of contemplation with the beatific vision. For St. Thomas, the virtuous life is framed as a way of perfection which finds its consummation in the last end: beatitude. It is the greatest good to which all other goods are ordered, and, holding that human actions are ordered to the good, St. Thomas concludes that the beatific vision, final happiness, is the fulfillment of all of human action. Ultimately, it is a rest that is given by God, that perfects all our potential, and that satiates all desire: heaven’s last best gift.

One of the virtues closely associated with man’s final end is hope. According to St. Thomas, it is hope of the final end that gives way to charity, which is the perfect love of God. So in a way, hope is one of the final virtues that must be acquired before the end can be attained. In Persuasion, it is precisely this virtue that Anne Elliot acquires throughout the course of the novel. She, who had been “forced into prudence in her youth [and] learned romance as she grew older,” must now learn to hope in order that she may know happiness once more.

As the novel begins, Anne is surrounded by harbingers of fading life: the time of year is autumn, her father’s line is in danger of extinction, and her family must let Kellynch Hall in order to make financial ends meet. On top of all this, she is oppressed by the prospect of her former lover once again being near her, and when he does arrive, she is made miserable in his presence. Mistakenly, she prepares herself to meet him with as much indifference as possible and to “teach herself to be insensible on such points” as meeting him and hearing others speak of him. In short, she harbors no hope for happiness and looks only to avoid as much pain as she can manage.

In the closing chapters of the first volume, there are such exquisite descriptions of the fading year that one cannot help but imagine that their narration is tinged by Anne’s despondency as she struggles to endure the affliction of a renewed, yet torturously more distant acquaintance with Captain Wentworth. Anne struggles to derive pleasure from “the last smiles of the year upon the tawny leaves and withered hedges,” mining the reserves of the contemporary poets for an “apt analogy of the declining year with declining happiness, and the images of youth and hope, and spring, all gone together.” She is withering in spirit, as she has done already in beauty, and she does not become fully aware of her closeness to despondency and despair until her discussions with the unfortunate Captain Benwick, in which she counsels him in “moral and religious endurance” in the face of the temptation to mourn ruefully over lost love.

And yet, in these last chapters, the reader finds the faintest glimmer of hope for new life and happiness in Anne’s reflections and experiences. After her conversation with Captain Benwick, she realizes just how close she had come to despairing of happiness, having sought to console another in his own loss and instill hope for the future. The morning after this conversation, Anne’s outlook begins to change for the better. She looks on nature with a more positive outlook than her November walk, praising the morning, glorying in the sea, and delighting in the fresh-feeling breeze. This internal change is mirrored by her external appearance, as she, along with Mr. Eliot and Captain Wentworth, finds herself coming into a second bloom of softened beauty.

Once she arrives in Bath, Anne begins to hope more consciously for greater happiness in life, freed from remorseful recollections of her actions in the past. Aided by the exemplary behavior of an old, poor school-fellow and the news of Louisa’s engagement to someone other than Captain Wentworth, Anne fully embraces this newfound virtue and lives in hopeful expectation of a life of happiness that is yet to come.

Of course, she is rewarded with marriage to the man she loves, but in comparison to the rest of Austen’s heroines, Anne stands out as living the most independent life of virtue; even the paragon of all things good, Fanny Price, does not quite learn to expect happiness apart from marriage with Edmund before providence intervenes. Anne’s is a more mature hope for happiness, which is not too surprising considering her superiority in age (Anne is, by far, the oldest of Austen’s heroines). Such a development is in line with Aristotle’s conviction that complete virtue took time to perfect and mature and, consequently, was rarely found in the young. The difference can also be seen in Anne’s ability to instruct others in virtue and Fanny’s conviction that she would be ill-suited for such a task.

As a result of her more solid foundation in virtue, Anne begins to develop a more independent sense of virtue. Impressed by the upbeat disposition of her poor and ailing friend, Mrs. Smith, Anne begins to contemplate a more stable and permanent source of happiness than that which the goods of this passing world can provide. Even before she begins to seriously hope for a life of happiness in a marriage to Captain Wentworth, Anne has proved herself capable of sharing in the happiness of others with little concern for any of her own selfish desires, as the many episodes at Uppercross and Lyme illustrate. More importantly, in the midst of her concern for the happiness of others, she does not compromise her own standard of happiness (“her feelings were still adverse to any man save one”). While it does not entirely depend upon the fulfillment of any single desire, Anne’s happiness does rest on a hope that finds its eventual fulfillment, its final rest, in love. Likewise, in this life, the gift of hope points us to our final rest: the vision and love of God.

✠

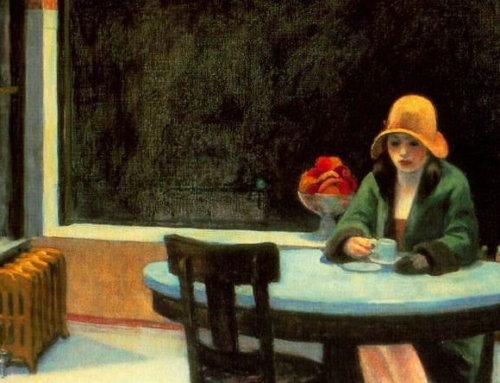

Image: John Atkinson Grimshaw, In Peril (The Harbor Flare)