The beatific vision is like a baby who has a beard.

This isn’t my own original idea. It belongs to Saint Thomas Aquinas (see De veritate q. 13, a. 1, ad 1), who used it to argue against the claim that in heaven we’ll somehow lose our humanity. If we spend time thinking about it, the beatific vision—the strange and glorious union with God that we will enjoy in heaven—can seem like something unnatural to us.

But Aquinas is very much opposed to the idea of the beatific vision violating human nature. He sees heaven as a place where people become more, not less, human. Union with God doesn’t substantially change what we are. Grace doesn’t break human nature, but perfects it. This is why Aquinas needs to refute the claim that the beatific vision is something inhuman, something unnatural.

To this end, he takes up the analogy of the bearded baby.

Saint Thomas distinguishes two senses of the word “unnatural.” On the one hand, “unnatural” can refer to that which is completely foreign to the kind of thing that it is. For example, it is unnatural for a pan of lasagna to have a beard. Beards are totally foreign to the kind of thing that a pan of lasagna is. In order for lasagna to grow a true beard, it must become something totally different. It must become the kind of thing that grows hair, namely, a mammal.

You can see why Aquinas wants to avoid using this sense of the word “unnatural” for the way we relate to the beatific vision. If the beatific vision were “unnatural” to us in this sense, that would mean that we would have to become something totally different—akin to a pan of lasagna becoming a mammal—in order to walk through the pearly gates.

So, Aquinas distinguishes a second meaning of the word “unnatural.” Something is unnatural, not because it is foreign to something’s specific nature, but because it is foreign to the current state of maturity of that thing.

Enter the bearded baby.

With his astute philosophical insight, Aquinas acknowledges that it is unnatural for a baby to have a beard. Not, however, because of the kind of thing the baby is (i.e., human). But because of the baby’s current state of development. The baby doesn’t have to become something totally different in order to grow a beard. It just has to grow up.

Another example is that of the oak tree. It’s unnatural for oak trees that are just sprouting to produce acorns. But it’s not unnatural in the same way that the bearded lasagna is unnatural. The oak tree doesn’t have to become something completely different in order to grow acorns. It just has to become more mature. Acorns are unnatural to it in its undeveloped state, but natural to it when it is fully grown.

Aquinas uses this sense of the word “unnatural” to describe our relation to the beatific vision. That kind of perfect, personal, everlasting union is foreign to our experience of what it means to know somebody. For this reason, heaven can be something difficult to imagine. It’s impossible for us to grasp what exactly the beatific vision will be like for us.

But this is because the beatific vision is something that we are not yet “old enough” (as it were) to understand. It’s something that doesn’t belong to our current state of spiritual development, just like a beard is something that doesn’t belong to the state of infancy. But that does not mean that heaven is something that is foreign to the kind of thing that we are. It doesn’t mean that paradise is ill-suited to human nature.

Rather, the life that we live in this world is like a stage of infancy. As long as we are on this side of eternity, we have not yet reached our full maturity as adopted sons and daughters of God. When that day finally comes, when we finally “grow up,” when we join the ranks of the blessed in the heavenly kingdom, we will discover that the life of heaven is truly what we were made for.

✠

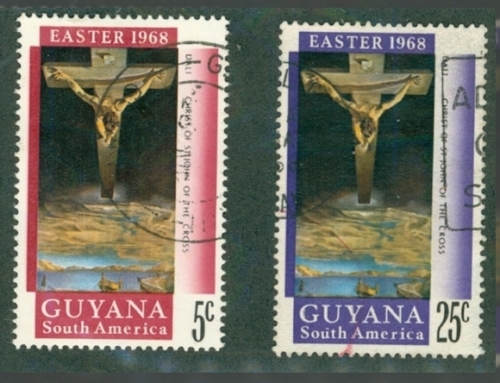

Photo by Ales Dusa on Unsplash