I am an occasional sufferer of what you might call “convert-envy.” It comes and goes, but sometimes I do find myself wishing that, like so many energetic, passionate converts, I had the experience of seeing the faith with fresh eyes, perhaps of jumping on board the bark of Peter with the gasping relief of one who’s been lost at sea. It’s not just converts to the faith, either. I often hear even fellow cradle Catholics describe a “conversion experience” they had, a particular moment of grace, healing, illumination, or what-have-you.

It strikes me that we tend to associate the “conversion experience” with a single, one-and-done event. It was a moment of crisis, perhaps, or of epiphany. Either way, it’s incredibly particular, a unique moment in time.

If we take this to be somehow the heart of Christian conversion, then I think that most of us, who have not had such a high-octane experience of concentrated grace, are stuck in a bit of a fog.

The trouble with thinking of conversion as primarily a one-and-done experience is at least twofold. First, it can blind us to the fact that the Lord has been working on us the entire time and will continue to do so–thank God–even once the fervor of that conversion experience has begun to grow cold. We should not discount the Lord’s careful work in leading us to those moments of particular grace. Second, the 180° model of conversion can lead us to orient our lives by that life-changing event and not by Christ. We may frame our current life in Christ negatively, as simply the opposite of what we used to be like or do. Our subjective experience becomes our north star.

Perhaps we should stop thinking of conversion as a one-time-only deal and understand it more as a much deeper, more continuous, and all-encompassing encounter with God’s mercy. Conversion is not only the dramatic, stage-lit moral revolution, complete with Hans Zimmer score. Even when it involves death to sin, conversion is never a rupture of a life; it might be better described in St. Paul’s words as a movement “from grace to grace.”

Here’s a metaphor that seems spot on as a description of this wider notion of conversion. In a rare and uncharacteristic burst of cultural enrichment, I was recently watching a performance of Bach’s Cello Suite No. 1 in G Major for the remarkable All of Bach series. In an interview, cellist Lucia Swarts drew attention to the way that she stresses the first bass note, that powerful, open G. One can’t, she explains, just rush from that initial bass note, bowing the notes as though they were all of equal value or importance. The harmony needs that bass note to have center stage. The careful positioning and added emphasis are essential because, as Ms. Swarts declared, “harmony takes time.”

Conversion, in short, is a gradual, steady tuning to Christ, the basso continuo, the throbbing pulse of the Christian life. Conversion is not a negative process or just a moral 180. Conversion is about Christ. It’s by reference to Christ as the tonic note (like that bass note in Bach’s piece) that our life becomes more attuned to God. That’s why the tradition will talk about the Christian life as divinization. We become like God, perfect as the Father is perfect, as we are tuned to Christ. By grace, the formerly discordant, random notes of our lives are brought into harmony with the song of the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit, and we join in the symphony of the saints.

And as our Dutch cellist reminds us, this harmony doesn’t happen in an instant. Not all the notes of our lives immediately find their place in the melody as soon as they’re sounded. Some are simply false or off-pitch, some are poorly played, some wait to find their place in the fuller melody. And yet God is not flummoxed by our ineptitude, our stubby fingers, our impatience, and tone-deafness. God is not a teacher who takes only the best and brightest. In fact, the Lord’s patience with us should teach us to wait in patience. Harmony takes time.

What this means is that conversion is for all of us, not necessarily because we have some huge, outsized sinning to convert from, but because sin and its effects, like spiritual dissonance, are always threatening to break in on the Christian’s song. For instance, most of us are well-stocked with garden-variety sins: we’re impatient, we gossip, we manipulate, we don’t pray, we complain. And yet these are crying out for conversion just as much as the flashier sins.

And unlike the 180° model, conversion-as-harmony involves all dimensions of our lives, not merely the moral. Conversion can also be a matter of choosing between good things, where choosing one means sacrificing the other. Or it can be a matter of dealing with those family problems, work struggles, illnesses, relationship issues, personal failures which can tempt us to see our lives as so much bric-a-brac. Conversion means learning to transpose even what is trivial or troubling into the master-melody of Divine Providence.

So, if we would be converted, we need to bend an ear to Christ, to learn the harmonies of heaven. It may not happen overnight, but that’s why we’re here. Harmony takes time.

✠

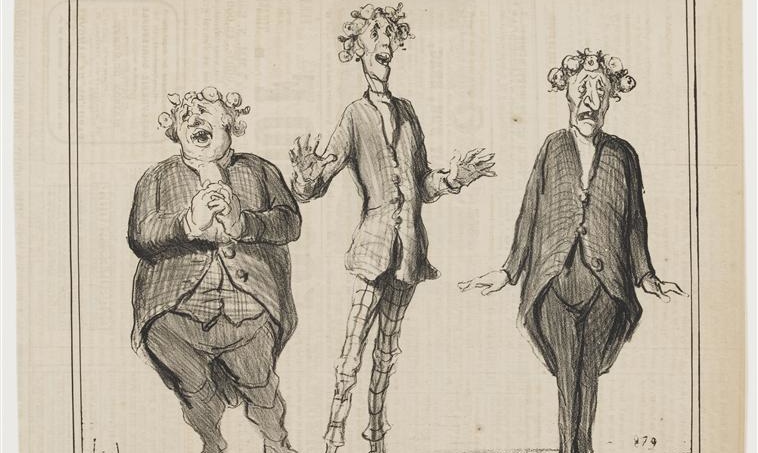

Image: Honore Daumier, Joyful Song Performed by M. Cobden