Forma Vitae: An Essay on the Dominican Life

A “forma vitae” essay is meant to convey something about the “form of life” that we, as Dominican friars, live in virtue of our religious vows. Each “forma vitae” essay should provide accessible, insightful, and revealing commentary about the Dominican life and vocation. Other “forma vitae” essays can be found here..

Ask any friar about God or the spiritual life and, inevitably, the word “grace” will come out of his mouth. This makes sense given the emphasis the Order places upon grace. Not only are there common modes of speech in the Order that incorporate this term—the Order of grace, preachers of grace, the life of grace, etc.—but, even the history of the Order is in some ways tied up with controversies about grace (see, for instance, the de Auxiliis controversy).

In fact, one might say that the whole of the Dominican life, summed up in “contemplare et contemplata aliis tradere,” (“to contemplate and to share with others the fruits of contemplation”) is framed within the reality of grace—the object of our contemplation is Uncreated Grace (God) and the gift of contemplation is a natural flowering of grace in the soul. Therefore, the content of our preaching, the animating principle of our spiritual life, the object of our study and prayer, the desire of our souls—all of these should be vivified by and immersed in grace. But what, exactly, do Dominicans mean by “grace” and how does this meaning relate to the soul of a Dominican friar?

When Saint Thomas discusses grace in the Summa Theologiae (ST II-II Q. 110, a. 1), he distinguishes three ways in which the word “grace” can be used. It first can be understood as being in the good “graces” of someone—as a soldier is to his king, i.e., the king looks on the soldier with favor. This marks the first desire of a Dominican soul—he desires, ultimately, to be looked upon with God’s favor. At the origin of the Dominican’s vocation, he, like the rich young man, is invited by Christ to give up all and follow him. But this invitation comes only after something more important: “Jesus looked on him, and loved him” (Mark 10:21).

This divine gaze does not cease after the initial call, however. Towards the end of St. Thomas’ life, Christ spoke to him from a crucifix. Christ said: “bene scripsisti de me”—“you have written well of me.” The divine predilection that brought St. Thomas into the Order was also manifest at the end—Christ still wanted to show St. Thomas his love. While the Dominican soul may not always receive supernatural locutions, he realizes, like St. Thomas, that the divine gaze that brought him into the Order will be manifest throughout his life—Christ still wants to show the Dominican his love. At the very end of his earthly sojourn, when asked what more he desires, the Dominican soul hopes to respond with the words of St. Thomas, “non nisi te, Domine”—“nothing but you, O Lord.”

Secondly, “grace” can refer to a free gift given. The Dominican knows that, ultimately, grace is God’s gift. And grace is required to live the Dominican life well. Without God’s help, I cannot be a holy Dominican because the Dominican life is a supernatural life; it is a life of the theological virtues. The fact that grace is a gift does not only affect the individual Dominican, however. The preacher lives in the humbling yet exhilarating position of being a mere instrument of divine providence—having known the one who is First Truth by faith and loved the Supremely Lovable One by charity, he burns with a desire to share him with others, to share this gift with others.

An early story of St. Dominic exemplifies this burning heart. While traveling through southern Spain, St. Dominic stayed at an inn where the owner had rejected the truth of the faith. Inflamed with zeal for the truth and a hunger for souls, St. Dominic stayed up through the night accompanying the innkeeper—who was immersed in the darkness of error—until the dawn from on high illuminated both the mind of the innkeeper and the rolling plains of the countryside. And while the sons of St. Dominic are not able to ensure the efficacy of their preaching, the greatness of God’s gift of grace urges us on. As such, we continue preaching—for the salvation of souls.

Thirdly, “grace” can imply gratitude for a gift given. The Dominican soul relishes the fact that he can witness the grace of God at work. He is given a glimpse of the whole economy of grace as manifested in the Order, in the Church, and in the world. From the communal recitation of the Divine Office to the reception of the sacraments, the Dominican loves to participate in and witness God’s mighty work. Indeed, the deepest joy of his soul is to sing praises to God’s name and exult before him (cf., Ps 68:4). Through his understanding of who God is and how God acts, the Dominican is able to come to an ever-greater understanding of God’s goodness. In response, he gives thanks and begs for more.

As St. Thomas concludes his treatment of the tri-fold meaning of the word “grace,” he observes that the three uses of the term all originate in the first—we give thanks because of a gift given, and we are given a gift as a sign of being in someone’s good graces. He notes one important difference though: in man, love is a response to goodness, but in God, goodness is caused by his love of a thing. As such, ultimately, the Dominican soul realizes that he has received the greatest gift imaginable: being at home in the world of grace, being at home with the Father, Son, and Holy Spirit.

Jesus answered and said to him, “Whoever loves me will keep my word, and my Father will love him, and we will come to him and make our dwelling with him.” (John 14:23)

✠

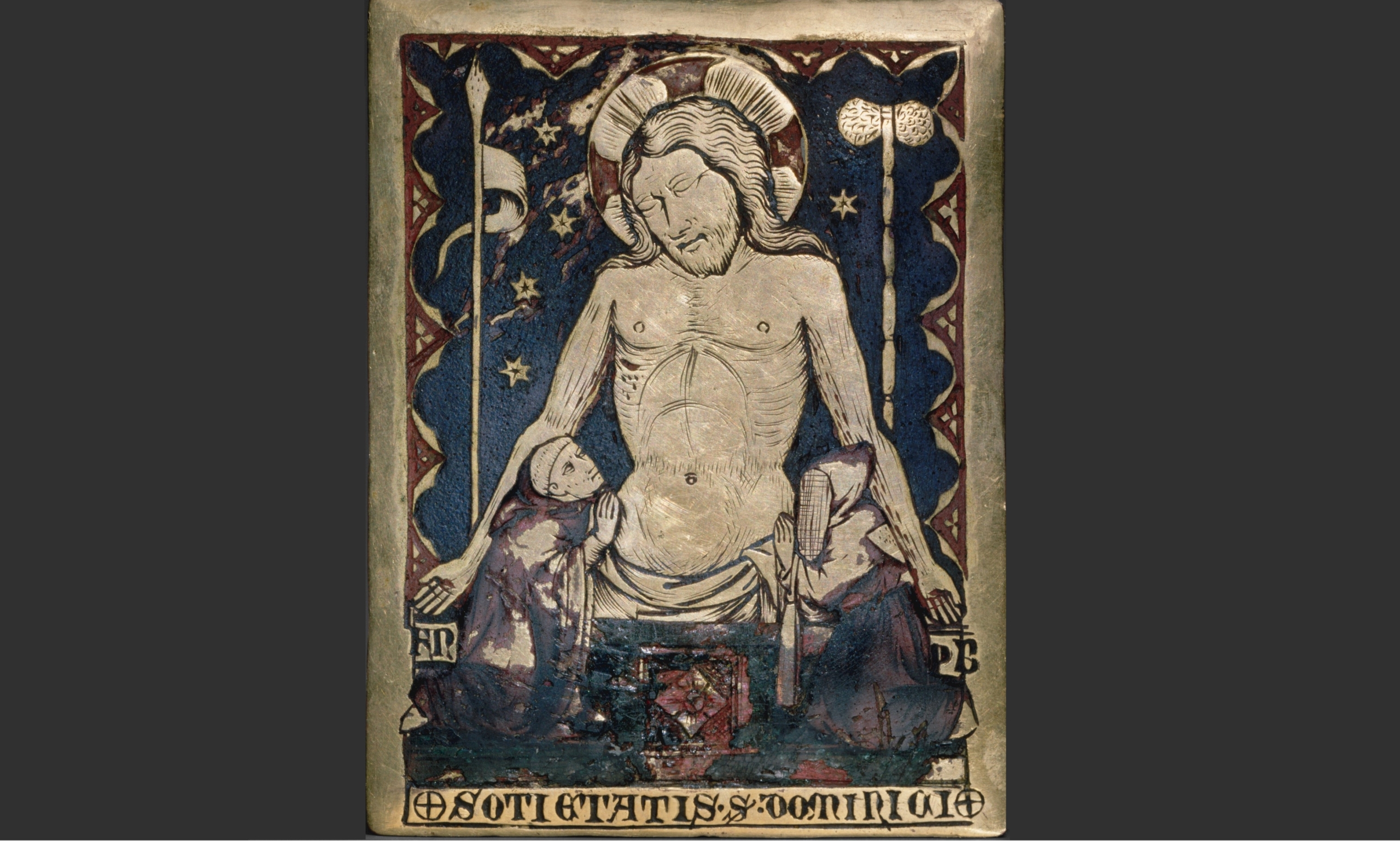

Image: Artist Unknown, The Man of Sorrows