Bill Wilson, co-founder of Alcoholics Anonymous, wrote that “few people will sincerely try to practice the A.A. program unless they have hit bottom.” He found that utter desolation—rock bottom, as we call it—often incited alcoholics to admit their helplessness and surrender to a higher power.

So, then, is rock bottom a good or a bad thing? Without downplaying the awfulness of suffering and how horrific the lowest low may be, I propose that the very idiom hitting rock bottom indicates a hopeful reality.

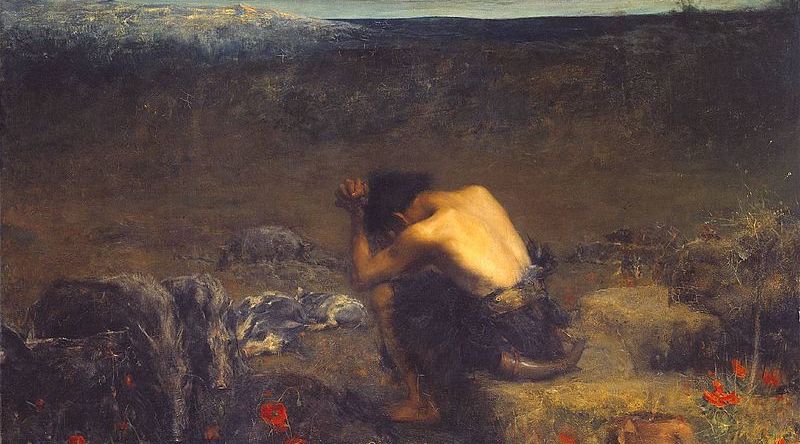

Hitting rock bottom is not an experience known only to addicts, and it looks different from one situation to another. The cause could be the loss of a loved one, a severe illness, financial ruin, depression, or one of a hundred other calamities. In every case, however, the term rock bottom evokes the image of a dark and immensely deep hole in the ground. The afflicted person is at its floor; he is wounded, seemingly alone, and certainly unable to climb out on his own.

At the same time—and this is the hopeful part—the man at rock bottom is unable to go any further down. He has struck solid, immovable rock. The image is apt because when it seems like all the good things we hold dear have been dug out from beneath our feet (whether by ourselves or not), there is always at the bottom one foundational reality that cannot be disturbed or extracted: God, the very ground of our existence.

The Bible is replete with accounts of rock bottom, and the message is always the same: God is still God no matter what happens. Consider this passage from the Book of Habakkuk:

For though the fig tree blossom not

nor fruit be on the vines,

though the yield of the olive fail

and the terraces produce no nourishment,

though the flocks disappear from the fold

and there be no herd in the stalls,

yet will I rejoice in the Lord

and exult in my saving God (Hab 3:17-18).

You may lose your house, reputation, savings, good looks, hair, health, and even your loved ones, but you cannot lose God. Even if “the mountains fall into the depths of the sea” (Ps 46:2), you can take refuge in the eternal, unchanging Creator. While everything else does not have to exist, God simply is. He always has been and always will be; he made you and all the good things you may have lost. He is the reliable adamantine rock on which everything stands, and, in fact, he is the only support you need.

Some holy men and women endure a kind of spiritual rock bottom. Though in the state of grace and indeed very near to God, they feel utterly empty, especially when they try to pray. Like the Crucified Jesus, the Man of Sorrows, they may even cry, “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” (Mt 27:46), and yet they also know in their bones that God is at their side, holding them in being. Thus, someone like St. Therese of Lisieux could write in her autobiography, “Spiritual aridity was my daily bread and, deprived of all consolation, I was still the happiest of creatures.” The saints know that God is near even in the darkness.

Someone at rock bottom likely may say, “It cannot get any worse.” Interpreted in one way, this is a bleak declaration of despair; in another, it is a sound confession of faith: As awful as things are now, I know they cannot get worse because “neither death, nor life, nor angels, nor principalities, nor present things, nor future things, nor powers, nor height, nor depth, nor any other creature will be able to separate us from the love of God in Christ Jesus our Lord” (Rom 8:38-39).

With faith, rock bottom is a sign of hope. When we fall into the depths—when our lives are at their worst—we do not descend forever into a black hole of meaninglessness. Instead, we meet God, who loves us and upholds us.

I love you, Lord, my strength, my rock, my fortress, my savior. My God is the rock where I take refuge; my shield, my mighty help, my stronghold (Ps 18:2-3).

✠

John Macallan Swan, The Prodigal Son