“Words, words, words,” replied Hamlet with despair-filled irony.

In a social setting suffused and encompassed by words, sound bites, snippets, and advertising, the mind cannot help but be overwhelmed. There is also the further complication that many of these words are unhelpful; things are not always what they seem, what they profess to be. When one’s glance falls upon abortion clinics named “Women and Family Centers,” stores selling exclusively pornographic and fetishist paraphernalia called “Adult,” and rock stars naming their children Dweezil and Moon Unit, it can appear that beyond being merely deceptive, some names simply fail to communicate altogether.

The medievals spoke about language as composed of signs. The word is chosen to communicate an idea, an idea in the mind which comes from a thing. The word was the verbal fruit of an idea rooted in something real. In this sense, words were conventionally chosen by man for the express purpose of revealing something about the thing at stake. Some even held that the words themselves, beyond just acting as a vehicle, had some proper reality. We can think in this case of onomatopoeia. The word signifies something else but in a manner that incarnates the nature. Affirmed above all was the sense that words are profoundly rooted in the real. Words are the fruit of a tree rooted in the soil of things.

It seems that the present age, as adverted to above, has forgotten the realities at stake in its use of language. In a technocratic age, wherein man seeks to extend his reign over nature both vast and miniscule, an appreciation for things as possessed of natures has been relegated to the background of our scientific considerations. This is all the more true when we speak of mankind, wherein the talk of passion, authenticity, and tolerance predominates over accounts of man’s nature. The individual, the seat of subjective rights, is the basic unit of the modern world, and consideration for his social, political, transcendent nature is relegated to the status of secondary concern. It is an age in the desert, forgetful of the land from whence it came and the promise to which it is called.

In a travel journal from a trip to Ireland, G. K. Chesterton contrasts this profound cultural forgetfulness with the deep rootedness observable in a culture (in 1918) still mindful of its roots:

It is strictly and soberly true that any peasant, in a mud cabin in County Clare, when he names his child Michael, may really have a sense of the presence that smote down Satan, the arms and plumage of the paladin of paradise […] It is often said, and possibly true that the peasant named Michael cannot write his own name. But it is quite equally true that the clerk named John [archetypal product of the industrial age] cannot read his own name. He cannot read it because it is in a foreign language, and he has never been made to realize what it stands for. He does not know that John means John as the other man does know that Michael means Michael. In that rigidly realistic sense, the pupil of industrial intellectualism does not even know his own name.

In the current cultural climate, the last thing we are likely to hear is the candid admission that we have “lost our way,” or worse yet that “we do not know our own mind,” but the facts seem to betray that such is the case. As the exasperated Israelite prophets would readily attest, there is no limit to our forgetfulness.

The fact remains that man is a mystery to himself and without the grace whereby to see, he remains such, constantly railing against God and reality on account of his limitation. In this sense, man is capable of “forgetting his own name.” And, as implied in the discussion above, to forget one’s name means to forget one’s own nature. To take the argument to its grim logical terminus, it follows that without a “still point in this turning world,” the obstacle can seem insuperable. How does man get on track when the very memory of the way has been blotted from his heart?

The prophet Jeremiah offers hope:

But this is the covenant which I will make with the house of Israel after those days, says the LORD: I will put my law within them, and I will write it upon their hearts; and I will be their God, and they shall be my people. And no longer shall each man teach his neighbor and each his brother, saying, `Know the LORD,’ for they shall all know me, from the least of them to the greatest, says the LORD; for I will forgive their iniquity, and I will remember their sin no more. (Jer 31:33-34)

Ultimately, the solution to man’s forgetfulness can be found only in the Lord’s gift—the new Law by which the Holy Spirit, the Spirit of Christ, is poured into the hearts of men: “Christ, the final Adam, by the revelation of the mystery of the Father and His love, fully reveals man to man himself and makes his supreme calling clear.” Such is the grace accomplished for man by the Incarnate Word. To that end, we pray for a new Pentecost.

✠

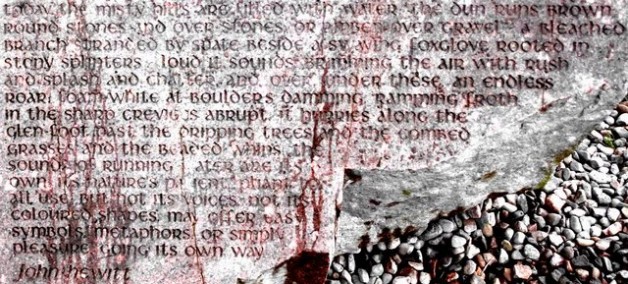

Image: Bob Embleton, Words on the Cushendun Stone