Ashlyn Blocker is in many respects a normal American teenage girl. She lives with her family, has fun with her friends, watches TV and sings pop music. But there is something different about her, something very different. After she was born she hardly ever cried. For instance, once she nearly chewed off her tongue while her teeth were coming in, but she didn’t cry or complain. It turns out she has a genetic disorder which blocks the electrical transmissions of painful events from reaching her brain. She has a congenital insensitivity to pain.

On the surface, that sounds like a problem that we would all like to have. Imagine the amazing things we would be able to do, and yet, not feel the painful consequences. It seems that congenital insensitivity to pain is a lot like a superpower. In reality though, it is really a super-disability.

In an article in the New York Times Magazine about Ashlyn and her situation, Dr. Geoffrey Woods, the geneticist who discovered the mutation, says about pain:

It is an extraordinary disorder. It’s quite interesting, because it makes you realize pain is there for a number of reasons, and one of them is to use your body correctly without damaging it and modulating what you do.

For Ashlyn, what comes as second nature to us, like pulling a hand away when it is getting burned, has been acquired through a lifetime of damaging trial and error. All those who share her condition know the benefits of pain and the danger of not experiencing pain.

It doesn’t take much searching to encounter someone who decries “Catholic Guilt.” It is portrayed as the experience of feeling bad for doing things that should be natural to us. It prevents us from being fully alive. It is a prison which rational adults should cast off as soon as they realize they suffer from it. I concede that many times, people feel guilty when they shouldn’t. This should indeed be cast off. But let’s not throw the baby out with the bath water.

As people of faith, we believe that each person is composed of body and soul. Just as dangerous things cause our bodies to feel healthy pain, so too does healthy guilt alert us to the fact that we are endangering our soul.

If we experience pain in our bodies, we ought to cease doing the action which causes that pain. If we set our hand on a burner, we pull it off. We are free to decide not to, but then our hand will be destroyed. If we experience guilt in an action we commit, then most likely we should stop doing it. Otherwise our soul will suffer.

Recall Dr. Woods’ finding, and substitute “guilt” for “pain” and “soul” for “body”:

It’s quite interesting, because it makes you realize guilt is there for a number of reasons, and one of them is to use your soul correctly without damaging it and modulating what you do.

Minor pains from cuts and bruises can be healed easily at home, just as minor venial sins simply need to be taken care of by an act of charity, devotion, or a simple expression of sorrow. But big pains—lost limbs, cancer, heart attacks—these need to be taken care of by a professional physician. So too, grave sins need to be taken care of by a spiritual physician. This physician is Jesus Christ himself, acting through the priest as his sacramental representative.

Often the healing regimens in the spiritual life are difficult, and they may involve cutting off activities and relationships that are dangerous. But we can have confidence that the Divine Physician knows exactly what he is doing, even if we don’t. His healing is our salvation. The prescriptions he gives out are remedies of love. They heal us and those around us. If we don’t take the medicine the doctor prescribes, then our health will get worse. If we don’t live out the life that Jesus Christ has shown to us through the Church, our soul will feel worse. The pain will still be there, but how will we treat it? Most forms of self-medication just mask the pain: alcoholism, careerism, living a double life, etc.

Often we can think of the life of sin vs. the life of the spirit as a legal drama. We want to do certain things, but there are laws that we try to avoid breaking because of various punishments that are imposed on us as a result. This is a poor way of looking at our lives.

On the contrary, in the life of the soul (and in the life of the body) our goal is to be happy. That is how we are made. We commit sin, though, when we search for happiness in the wrong places. We try to be happy, yet we hurt ourselves, and we hurt others. Just think, when we are not feeling our best–a cold, a stomach-ache–we can be crabby, we can want our alone time. When we are sick in our soul we suffer from similarly isolating behaviors. However, we can recognize the pain that we feel, be healed, and learn more about what activities cause us pain. All we have to do is make an appointment.

✠

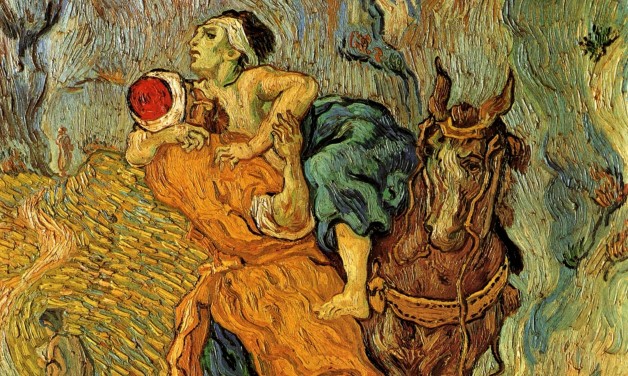

Image: Vincent van Gogh, The Good Samaritan, after Delcroix