We all know people whom we admire and try to imitate, mentors who show us how to live well. And there are those whom we try not to follow. Most would call themselves just and fair: we know that is how we should be. The civil rights leaders were heroes because they stood up for justice; those who opposed them, those who defended racism, we know to have been wrong. We know it, we don’t just believe it. We know that it is better to be just than racist. The same goes for other values. It is better to be an honest person than a liar and a swindler. It is better to be temperate in food and drink than an addict. It is better to be courageous than cowardly. What father would want his son to be a thieving drug-addict, or a vicious criminal, or a racist propagandist, or an alcoholic? There are certain ways of living that all sane people recognize as ideal. Traditionally these are called the virtues: those character traits that mark out the good man.

The virtues are not arbitrary or culture-specific. They may take different forms within different cultures, but in essence they transcend the diversity of cultures. All legitimate cultures acclaim the just man and decry the liar, hail the hero and boo the coward, reward the wise and pity the foolhardy. The virtues are stable across their diverse cultural expressions because all cultures are united in one thing: they are composed of men. What unites all men is that we are human.

But some deny that we have human natures. Saying that I’m not human does not make me something else; it just makes me a fool. I can claim to be a jelly donut, but I am not thereby a donut, but a good applicant for a mental ward. To extol lies and injustice does not redefine justice, it just makes one dangerously wrong. In the words of a wise sailor: “I am what I am” (cf. 1 Cor 15:10).

But what does it mean to be something? It means that the meaning in our lives is linked to what we are. We are meant to be good humans—like dogs who fetch are good dogs, and cats who purr are good cats, and so on. We find fulfillment and happiness in being a good human, and being a good human means being virtuous. Just and honest men, wise men, men who can sleep at night knowing that they did what was right, are good and virtuous men. Denying that such is the case does not undo its truth, it only makes one ignorant. An evil man who rationalizes his evil, like a drug-dealer who claims that he is only giving people what they want, or a slaver who says that slaves aren’t really men, is still just evil. And those who claim that they create their own meaning in life are just as confused. We did not create ourselves, and did not make ourselves human, but that still is what we are.

The serpent in the Garden of Eden tempted Eve by telling her that “ye shall be as gods.” The same temptation exists today: that we can create ourselves and thus be as gods. But we did not create ourselves, and did not choose to be human. Yet that is what we are. We have been given the gift of existing and being human, and the meaning of our lives lies in fulfilling what we have been given. Ultimately that means being called to live with God in heaven, with Him who created us. The question is always the same: do we accept who we are, and live as God’s creatures in happiness, or do we deny God and the truth, and pretend to be as gods? Do we choose heaven or hell?

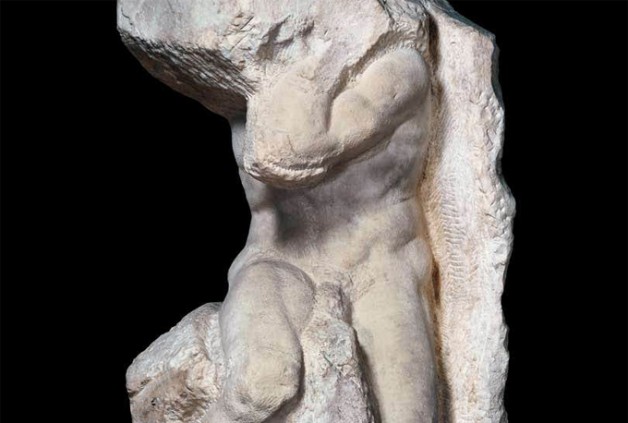

Image: Michelangelo, Atlas Slave