I suppose even nuns need to have fun from time to time.

Saint Thérèse of Lisieux was known to write and direct “pious recreations” for her sisters. These plays had singing, scripts, costumes, props and all!

In one of these plays, The Angels at Jesus’s Manger, the cherubs express a desire to die—yes, truly to die as men die.

“Before You, sweet Child, the cherubim bows down!

Dazed, he admires Your ineffable love.

He wishes, like You, on the somber hill

To die one day!” (130)

This seems odd to a Dominican. After all, death is not proper to the angelic nature, for they do not have material bodies. Thus an angel would not, and indeed could not, desire death. It would be contrary to their nature. I can almost hear a friar saying: “Well actually, Saint Thérèse.… ”

But perhaps the saint has another purpose in mind than to discourse about angelology.

Leading up to this professed desire to die, the angels find themselves conversing with one another at the foot of Christ’s crib, while slowly learning more and more about why exactly God has become man. They quickly recognize that their Lord will be spared no aspect of the painful human experience.

“Ah! Let me take you to Heaven, since earth has nothing but sorrows for You … But no … I see in your infant’s look that the cross has more charms for You than the eternal throne of the heavens … I cannot comprehend the immense love that made You to descend to earth … Must it be that Jesus … should be wounded by those cruel thorns?” (116-117)

Against all their angelic instincts, instincts of loyal servants for their king—that this divine child should be crowned with roses and gold and protected from those who would harm him—the angels come to learn that “Jesus wishes to suffer, he wishes to weep to redeem his brothers on earth!” (117)

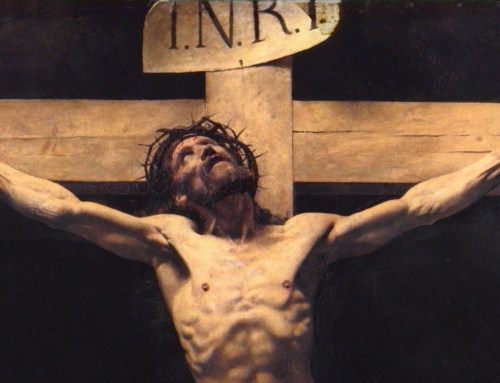

If the purpose of God becoming man is to redeem men, then the peak of Christ’s earthly life, and the most glorious of his human actions, is his death on the cross. It is by his death that we are redeemed from our sins (ST III q. 49, a. 1). His death delivered mankind from Satan’s power (a. 2). Through Christ’s death, God has reconciled us to himself (a. 4) and opened the gates of heaven to us (a. 5).

Since Christ has offered his life unto death out of love for the Father, then his followers should also wish to offer their lives, even unto death, out of love for the Father. Men can imitate the most brilliant and magnificent act of Christ: dying out of love.

And herein lies the Theresian angelic envy. The Incarnation grants to men something angels cannot claim—being consubstantial with the God man. This divine gift to us, this extravagant act of love and condescension, ought to inspire in us a burning charity (ST III q. 1, a. 2).

Little Thérèse wants you and me to read Saint Paul a bit more closely: “For if we have been united with him in a death like his, we will certainly be united with him in a resurrection like his.” (Rom 6:5) Men—and not angels—can die.

Saint Thérèse has placed her own prayer of thanksgiving for the Incarnation upon the lips of her playacting angels:

“How great is the good fortune of the human creature.

The seraphim in their ecstasy would wish

To leave, O Jesus, their angelic nature

And become children!” (130)

Truly—how great is our fortune! “The only-begotten Son of God, wanting to make us sharers in his divinity, assumed our nature, so that he, made man, might make men gods.” (Catechism of the Catholic Church, 460) Now that is a reason to sing and give praise like the angels in heaven!

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)