Many of us begin emails with generic phrases like “I hope you are doing well.” Saint Catherine of Siena began her letters with greetings like “I long to see you engulfed and drowned in the sweet blood of God’s Son, which is permeated with the fire of his blazing charity.”

Saint Catherine wrote thirty-seven of these fiery exhortations to Dominican friars. In them, she invites and implores her brethren to discover, to be immersed in, and to preach the transforming power of Christ’s Passion.

The discovery of Christ’s Passion begins in what St. Catherine calls the cell of self-knowledge. Illumined by the Holy Spirit in prayer—and, St. Catherine adds to the friars, amid their fidelity to their physical cells—we realize the depth of our own poverty. Everything we are—whether by nature or by grace—is a gift of God. Left to our own resources, we are not.

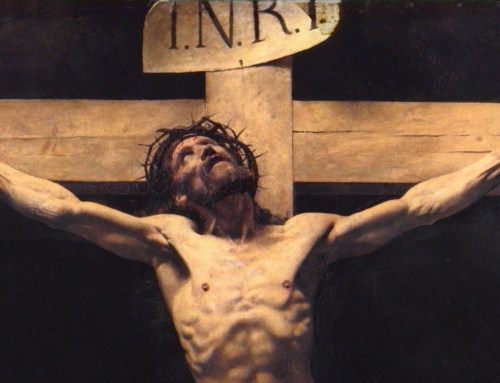

Saint Catherine writes that dwelling in the cell of self-knowledge leads us to discover the magnitude of God’s goodness to us. We discover for ourselves that Jesus went to the cross out of burning charity for us: that he ran to the cross for us like a lover or a courageous knight. Likewise, we realize that charity itself was what held Jesus to the cross—that the nails themselves could not have fixed Jesus to the wood if his love for us did not hold him there.

Pondering his love on the cross leads us to draw close and to accept being transformed by Christ’s Passion. Saint Catherine describes this change as an immersion in blood and fire: she writes of being “drowned and transformed in his overflowing blood,” of being “swallowed up—drowned—in the fire of God’s blazing charity.” This is a drowning—a dying—of the old self and its selfish ways of loving. It is also a bathing and a clothing in the fire of the Holy Spirit.

Saint Catherine compares this transformation to a kind of drunkenness. The blood of Christ crucified “is a wine on which our soul gets drunk,” and the lover of Christ’s blood is like a heavy drinker who forgets himself, immersing all of his thoughts in the wine. Such a man drinks and drinks and drinks until “his stomach becomes so warmed by the wine that he can no longer hold it, and out it comes!” Like the best of wines, Christ’s blood warms the heart and loosens the tongue. It rouses the soul from apathy and propels it outward to preach the truth with fire.

“Up, up,” St. Catherine urges. “No more sleeping.” Drowned and bathed in the blood of the Lamb, the friars are to run with zeal to the battlefield, seeking God’s honor and the salvation of souls. They are to imitate the apostles who “mounted the pulpit of the blazing cross, where they felt and tasted the hunger of God’s Son, his love for humankind.” Saint Catherine implores the friars to preach from the pulpit of the cross and to be consumed there with Christ’s desire; only then can their words burn like red-hot knives from a furnace to pierce their hearers’ hearts.

Saint Catherine bluntly acknowledges that the brethren should expect rejection in their ministry. True servants of Truth are not mercenaries who live for spiritual consolations. They do not flee from hard tasks or hard people. Instead, they remain on the battlefield, finding their rest and joy in their crucified captain. The fiery blood of Christ gives them strength “for every battle—for enduring pain, slander, reproach, and abuse for love of him.” This blood replaces their small-heartedness with Christ’s own great-heartedness, and it allows them to share Christ’s love and zeal even toward grumblers and persecutors.

Together, St. Catherine’s letters to friars are an accessible entry-point to her spiritual doctrine, tailored to men of the cell and the pulpit. Their fervor and directness pierce through our complacency and alert us to the reality at the heart of St. Catherine’s vision of Dominican life: immersion in the blood and fire of Christ crucified.

✠

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)