In April of 2022, a few months before taking the Dominican habit, I walked around the Notre Dame campus with a Dominican friar. A question had been on my mind for some time. “Father,” I said, “I don’t think I understand Easter.”

He chuckled at such a vaguely direct way of opening a discussion, then graciously listened as I tried to better explain my meaning: “Every Lent, I do penance, I pray more, and I strive to avoid sin. But when the celebrations of Easter are over, and the quiet Easter season days come, I look at myself and see the same person that I saw on Ash Wednesday. How do I rejoice in Easter without returning to my old ways?”

He replied with an understanding but cautionary tone, “Easter doesn’t mean that we’re done, that the work of the Christian life is over. It’s a time of new life, of growth.”

I’ve thought about those words every Lent and Easter since. They’ve brought me a better understanding of these seasons, and that’s enabled me to live them with more peace and more joy.

As I look back, I see that I expected Easter to bring me both pleasure and peace of soul. After the asceticism of Lent, I wanted to rest and let my inhibitions down, I wanted to enjoy myself without restraint. But this kind of transition from penance to Easter joy still looked more like a jump from rehab to relapse. As that good Dominican father pointed out to me, Easter is not the end of the Christian life. At least, not this Easter, not my Christian life. Easter is a season of growth, which means we are not done yet—we are not home. Even after such a great feast, we’re still pilgrims.

The Church has always seen the crossing of the Red Sea as a foreshadowing of Easter. After four hundred years of slavery and oppression, God brought his people through the sea on dry land, with the water like a wall to their right and left, and he drowned all their persecutors in its depths. Surely, after such a glorious victory, the Israelites finished their triumphant canticle and said to themselves, “We are free! Now, we can rest.”

Yes, they were free—pharaoh and his army had been cast into the sea. Yes, they could rest—their persecutors were dead. But when they turned from marveling at the surging, saving waters behind them, did they see the hills of milk and honey? No. Instead, they saw a barren desert. They were free, but there were still enemies to face, both in the lands ahead and in their own hearts. They could rest, but not for too long nor too complacently—there was still a road before their feet. They still bore in their bodies the marks of the Egypt they thought they had left behind. They had been saved, but their salvation was not complete.

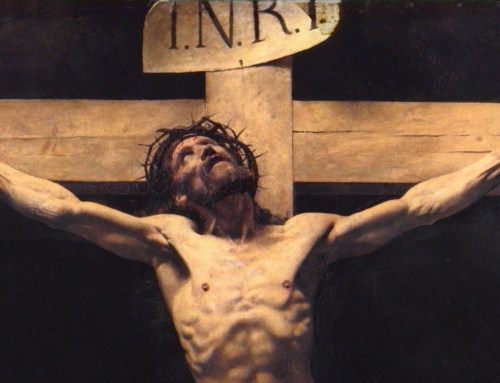

The same is true for us. Christ our Passover has been sacrificed; let us rejoice and be glad. But let us not suppose that our Passover, the sacrifice of our lives in union with his, is complete. Rather, we must fill up in our bodies what is lacking in the sufferings of Christ. We are dead to sin, truly. But how can we who are dead to sin still live in it? Christ has passed into the heavens, and our humanity with him, but we have not. We must not allow ourselves to be fooled by our weary bodies and our wily enemies; we are still a pilgrim people.

Between us and the promised land stand seven deadly enemies, aligned with the sinfulness of Egypt remaining within us. Let us take manna as our food, the cloudy sight of faith as our guide, and the Word of God as our sword. Let us rest not until God has given us rest from our enemies on every side, until our feet are standing within Jerusalem’s very gates (cf. Ps 122).

✠

Image: American Colony (Jerusalem) Photo Department, Mount Hermon and Vicinity (public domain)