Note: As part of our special Jubilee Edition, we are featuring this essay from Dominicana’s first issue by Fidelis Conlon, O.P, (1897-1915): Easter 1916. —Editors

True ideas are practicable. They represent something that is possible of attainment. They encourage imitation. Such are the Dominican Saints, the ideals of the Dominican Order. Enjoying eternal bliss beneath the protecting mantle of Mary, may be found models for all Dominicans. These models hold the secret of sanctity. To discover it we must read their lives. There we find that an intense love of the Passion has peopled the courts of Heaven with white robed Saints.

The crucifix has ever been the great book of Dominican perfection. Written by Almighty God in the Precious Blood of His only Begotten Son, it teaches the science of the Saints. Ignorant and learned, king and slave have studied it with success. All can understand its simple story. Dominicans especially have profitably opened that book of divine love and sacrifice. It was an object of their special veneration. Many fell under the weight of the cross, but not one cast off the heavy burden. No Dominican can be an unwilling Cyrene, and at the same time a loyal follower of Dominic.

The Holy Patriarch and Founder, St. Dominic, leads the white robed procession up the rugged ascent of Calvary. As a youth, he was an eager, loving disciple of the Suffering Redeemer. The Passion was the devotion having first claim on his heart. As a student he read and re-read the Epistles of St. Paul, till the spirit of the Apostle of the Gentiles, fired the heart of the Apostle of the Albigenses. It was only natural, then, that every thought, word and deed of the first Friar Preacher should be characterized by a burning love of the Crucifix, since St. Paul preached nothing but Jesus Christ and Him crucified. Dominic true to his name was Lord-like, especially in his desire to suffer. His Gethsemani was the plains of Languedoc. His chalice was the terrible Albigensian heresy. Daily scourgings, penances, vigils, and mortifications were offered in honor of his Suffering Lord. Nothing was left undone which might make him more conformable to the Model on the Cross. Truly, Dominic preached a love of Jesus Christ and Him crucified, first by example and then by word.

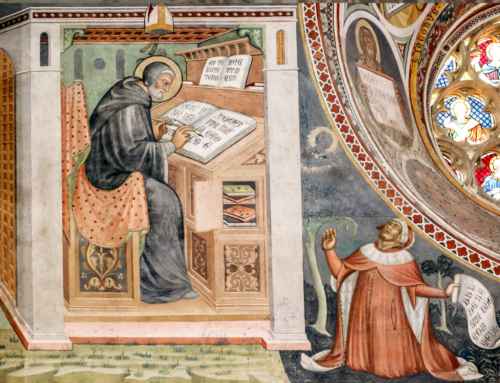

Artists seem to have found inspiration in Dominic’s love of the Cross. In the church of St. James at Muret, there is a picture representing the Saint receiving the Rosary from Mary. In his right hand he holds the much treasured Crucifix. This painting clearly shows how well known must have been Dominic’s devotion to the Crucifix. There is another picture which is more familiar and more expressive. It is the one of our Holy Father praying before the Image of the Crucified. If art is silent music, what responsive chords must that picture strike in the hearts of all lovers of Dominic! There we see Dominic as the saint. With clasped hands, his countenance sympathetic with sorrow, his eyes closed to everything but the suffering Jesus, he asks for a share in the Sacred Passion. Nor does he forget his children. Knowing the power hidden in that Cross which rests against the very Gates of Heaven, he asks that a love of the Passion be given to all Dominicans. His request also embraces all religious souls striving to walk in the footsteps of the saints. That his prayer was answered, is evident from the following extracts from Dominican lives.

Following Dominic, the great Angelic Saint and Doctor, St. Thomas Aquinas stands out prominently. The learning of this Christian Aristotle and his efforts in behalf of true philosophy and theology were surpassed only by his love of the Crucifix. His masterpiece the Summa Theologica, was written on Calvary. Immediately after his necessary intercourse with the world was ended, Thomas opened that book of divine suffering. In the depths of the Sacred Heart he learned the secrets of that wonderful work of which ‘‘every article is a miracle.” Theologians are often Dominicans and the Crucifix perplexed by the teachings of the Angelic Doctor and admit an inability to fathom their depths of meaning. This is sometimes due to a faulty method of study. To perfectly understand the doctrines of Aquinas there is needed something equally important as intellectual equipment. It is a prayerful, meditative study of the textbook of the Saint—the Crucifix. The Summa is the sum of the teachings of the Master hanging on Calvary. It is the fruit of hours spent before that bleeding Figure. One incident especially throws much light on the motive and end of all the Angelic’s labor. Having completed an important work, Thomas offers it to Jesus on the Cross. That act was pleasing to the Savior who deigned to express His approval in a miraculous manner. The Figure on the Crucifix addressed His client saying: “Thou hast written well of me Thomas. What reward wilt thou receive for thy labor?” The response gives us an insight into the character of the Saint. It was the answer to Dominic’s prayer. The Angelic replied, “None other but Thyself, O Lord.” We may marvel at the learning of the Saint, but we must marvel still more at the conformity between the Angelic Doctor and His Master on the Cross.

Since the Papal Throne is established on the Cross, we look to Calvary for its occupant. It is a fitting place for the Vicar of Christ. Our glance is rewarded. At the foot of the Cross kneels a celebrated Dominican Pope, St. Pius V. The world knows Pius as the Pope of the Rosary. His brethren know him as a lover of the Cross. When the Turks threatened Christendom, Pius united the Christian armies in defense. In comparison, the Christian army was small, yet the Turks were overcome at Lepanto. It was another Constantinian victory by the sign of the Cross; for the standard of the army, blessed and presented by Pius bore a large Crucifix. What power on earth could stand before that sign suspended from Heaven by the golden chain of Mary’s Rosary? The Pontiff’s devotion to the Crucifix had helped to win the victory. This was not the only miracle attributed to the Crucified Savior during the life of the Pope. The Saint’s love of the Passion once saved his life from the treachery of enemies. As was his daily custom, Pius spent many hours before the Crucifix. He raised the Figure to kiss the Sacred Wounds. The Feet parted so that his lips did not touch them. In all humility he believed that he had caused the displeasure of Jesus by some sin. Some members of the household, however, seeing the incident and having good reasons to think otherwise, wiped the Feet of the Image with bread. The bread was then thrown to dogs that immediately perished. Jesus had miraculously preserved St. Pius from death by poisoning, in grateful appreciation of his tender love and steadfast devotion to the Sacred Passion.

The daughters of St. Dominic rivaled their religious brethren in their devotion to the Cross. Their lives were marked by heroic voluntary suffering. No pain was too great for their love. St. Catherine of Siena was the first of those to whom our Lord revealed “the secret of His Sacred Heart.’’ Constantly engaged in familiar converse with Jesus, she asks Him “to take away all comforts and delights that she may take pleasure in no other thing but only in Him.” She pleaded with Christ to let her share His sufferings. “If I cannot be with Thee now in Heaven, she said, suffer at least that on earth I may be united to Thee in Thy Passion.” Her petition was granted. During the rest of her life she suffered intensely both in mind and body. Even the supernatural privilege of the Sacred Stigmata caused so much pain “that she thought she must die.” This impression of the Five Sacred Wounds transformed her into “a seraph dyed in the Blood of the Lamb.” Often she was mysteriously bathed in the Precious Blood and so great was her love of the wounded Savior that the mere sight of anything red made her weep. The whole life of St. Catherine of Siena may be summed up in one sentence—“an ardent desire to be united to the Divine Tree and transformed in Christ crucified.”

Another daughter of St. Dominic, St. Catherine de Ricci asked the Divine Spouse for a share in His sufferings. The impression of a Stigmata similar to that of Catherine of Siena was the response. This Stigmata caused intense pain yet Catherine de Ricci was not content. She then put a crown of thorns on her head. Even this was not all. Her Sisters in religion testify that from her Dominicans and the Crucifix right shoulder to her waist there was a deep wide furrow caused by the Cross she mysteriously carried every week.

To St. Rose of Lima is given the credit of inventing extraordinary methods of showing her love for the Crucifix. Hers was a wonderful devotion. Every day she embraced a large wooden cross in her cell. Wherever she saw a cross, she knelt down in adoration. Buried deep into her flesh was a crown with ninety-nine sharp points which she often changed in position to open new wounds. On one occasion she tied her hands to the cross in her cell and hung suspended in the air. On her deathbed in order that she might expire like Jesus, she had a cross placed under her head and shoulders. St. Rose the first flower of Sanctity in the “New World” thrived under the shadow of the Cross.

From the lives of these few Dominicans may be learned the spirit of the whole Order. Love of the Crucifix was not confined to a few. It was a family devotion, practiced by all. Others besides those known as canonized Saints have shared in that devotion. Little Imelda, though a mere child, erected a miniature Calvary in her cloister garden where she was wont to spend her time with Jesus. Henry Suso for eight years wore on his shoulders a cross studded with nails and knew no resting place other than the hard wood of the cross. John Tauler spent his life meditating on the Passion so that he might teach others its value. Even in comparatively modern times Lacordaire most zealously guarded that heritage of St. Dominic. A burning love for the Crucified Savior was the power with which the eloquent Dominican moved the vast audiences of Notre Dame. In order to feel something of the sufferings of the Sacred Passion, Lacordaire had himself fastened with ropes to a cross where he hung for three hours. Lacordaire became a Friar Preacher in order to be able to exercise his great devotion to Jesus Christ Crucified. He recognized the special honor in which Dominicans had always held the Passion. This particular devotion first attracted him to the Order.

The legislators of the Order have always kept alive that devotion. The Dominican Constitution ordains that in every cell, chapter room, classroom, refectory, and recreation room there must be a crucifix. It also prescribes that the religious on entering any of the above rooms must incline their head towards the Image. Moreover General Councils of the Order have admonished and strictly commanded the brethren “to preach nothing but Jesus Christ and Him crucified.”

Is not this devotion to the Passion a glorious tradition? The seed sown by Dominic had taken root and bore fruit a hundredfold. The motto of the Dominican Order is “TRUTH.” In no better way have Dominicans lived up to this motto than by fostering devotion to the Tree of Life on which “Truth” Itself has been nailed.

Christ told us that no one could go to the Father but through Him, for He was the way, the truth, and the life. Some of the white robed children of the Order of Truth have gone to eternal life. They followed Dominic along the way of the Cross. It remains for us to follow in the footsteps of our Model Saints, by imitating their love of the Crucifix.

The following is adapted from an obituary in the Fall 1959 issue of Dominicana (Vol. 44 No. 3).

Thomas Fidelis Conlon was born in Waterbury, Conn., on June 3, 1891. After his graduation from Aquinas College, Columbus, Ohio, he entered the Dominican Novitiate in Somerset, Ohio. He completed the required curriculum of philosophical and theological studies and also received the degree of doctor of literature and the licentiate of Canon Law in Washington, D. C.

As a young priest he was appointed Army chaplain in 1917 at Camp Shirley, Accotink, Va. Following this assignment, he taught Greek at La Salle Academy and Providence College, both in Providence, R. I. Then he was appointed to the Dominican Eastern Mission Band and in 1928, he was made superior of the Western Missionary Band in Chicago, Ill. From 1931 to 1938, Father Conlon Dominicans and the Crucifix 45

assumed the national directorship of the Holy Name Society. He also served as national director of the Rosary Confraternity and manager of the Dominican Publications Bureau. While acting as the executive secretary of the National Convention of Holy Name Societies, held in New York in 1936, over a national CBS radio hookup on the “Church of the Air” program, Father Conlon instituted the annual national observance of Holy Name Sunday on the second Sunday of January.

In 1938, Father Conlon was appointed pastor of St. Raymond’s Church, Providence, R. I., where he remained until 1944 when he returned to his former role as a missionary and retreat master.

His labors were publicly recognized in 1937 when Father Conlon was decorated by Pope Pius XI with the Papal Cross “Pro Ecclesia et Pontifice.” In 1951, the Dominican Order honored him with the title of Preacher General.

He died on April 20, 1959, in St. Mary’s Priory in New Haven, Conn., where he had been stationed while fulfilling his assignment as missionary and retreat master.

May he rest in peace.

To see a PDF of this article, click here. To see all the archives from 1916-1968, click here.