“CRY what shall I cry?” In Eliot’s Coriolan II – Difficulties of A Statesman, the statesman repeatedly asks this question. He begins to get an answer as the allusion to Isaiah is confirmed: “All flesh is grass.” But the Word is cut short by the difficulties of the statesman. There are committees to be formed, military orders to be recognized, secretaries to be appointed, and salaries to be paid. He dreams of serenity and stillness, even calls for his mother, but his duties continue to barge in, disturbing this dream.

The full Scriptural reference is: “A voice says, ‘Cry!’ And I said, “What shall I cry?’ All flesh is grass” (Isa 40:6). And a few verses later the section is completed: “The grass withers, the flower fades; but the word of our God will stand for ever” (Isa 40:8). John the Baptist will later identify himself as this crying voice (Jn 1:23). He cries to prepare the way of the Lord – the Word that speaks forever. But there are those who didn’t hear John, or didn’t want to. And there are those who cannot hear the Word, like Eliot’s statesman. The life of this latter statesman is one of distraction, drowning out the Voice of his calling.

Distraction seems to be one of Eliot’s major themes. We have our unfortunate Mr. Prufrock who wanders the streets of Boston, feebly pursuing a disinterested woman, perfecting the art of wasting hours. But he’s too bothered and enervated by these pursuits to force the moment – to ask the question – The Big Question that might reveal these empty pursuits for what they are.

There’s the broken attempt at communication in the Wasteland between two lovers:

“My nerves are bad to-night. Yes, bad. Stay with me.

Speak to me. Why do you never speak? Speak.

What are you thinking of? What thinking? What?

I never know what you are thinking. Think.”

But no connection is established between the two, which sheds light on the emptiness of the physical love shared between them.

We find this theme most clearly in the Four Quartets where Eliot directs our gaze to those faces:

Distracted from distraction by distraction

Filled with fancies and empty of meaning

Tumid apathy with no concentration

Distracted from distraction by distraction. Here Eliot is most explicit and also pins the problem down. We’re many levels removed from focus. We have so many fanciful pursuits: projects, patterns, people, and places; and we find new ones as we go through life (here I’m referring to empty, trifling pursuits – there are of course plenty of meaningful ones). We find we need them. We need distraction. Why? Because it keeps us from noticing we’re distracted in the first place. And if we came to terms with our distraction then we would have to find out what lies beneath it. We have a hunch there’s something there, and if we uncovered it, we might not like what we find.

I don’t need to rehearse the distractions we find in contemporary life. They’re obvious and everywhere. And in some sense we will always have them. The goal of life is not to annihilate distraction. But we should be on guard against those kinds which block God’s voice. Eliot’s Prufrock, Coriolanus, and wasteland lovers are examples of what can happen when we get distracted from what’s important in life. And we can really only discover what’s most important when we’re listening. So yes, it can be hard to discover what’s underneath all the noise in our life. But once we recover stillness, we also recover (or find for the first time) an ear for God’s voice – the Word that speaks forever.

✠

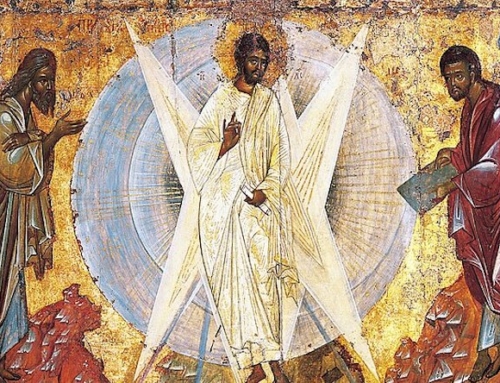

Image: Soma Orlai Petrich, Coriolanus