Could I?

In the days following California Governor Jerry Brown’s decision to sign physician-assisted suicide into law, The Economist promoted the pro-euthanasia materials they first published in June. Among them is this brief, pathos-driven video:

So, could I live a life like this?

Staring at sterile, comfortless white walls? Lying beneath numbing florescent lights? Subjected to the incessant beeping of monitors? These conditions make one feel that life is, well, lifeless. (The pensive music, reminiscent of the brooding American Beauty soundtrack, also contributes to the pit-in-the-stomach effect.) The stillness of the camera shot adds to the sense that my condition has rendered me entirely immobile. This would be it. This would be my fate. To stare up at this blank scene for the remainder of my final, agonizing days.

Now, there are various ways one could argue against the cause for which The Economist is advocating. (Actually, we might begin by highlighting the peculiarity of a news and commentary magazine taking upon itself a political campaign.) We could list the logical fallacies found in their main editorial: the appeal to majority, false alternative, and so on. Or point out that they do not address the slippery slope this law pushes society down. Or, on a more philosophical note, I could argue that I did not will myself into existence, that I did not decide to be born. Why then should I get to decide when and how I die? There are also the natural law arguments against euthanasia. It’s even worth examining how proponents want to change, and thereby defang, the very term used to describe the procedure we’re talking about here: “Physician-assisted suicide”? That sounds unpleasant. “Doctor-assisted dying,” as The Economist has it? Okay, better… “Death resulting from the self-administration of an aid-in-dying drug”? Yes, perfect!

None of these arguments mute the heart monitor or soften the glare from those fluorescent lights, however. In other words, these arguments do nothing to mitigate the fear instilled by the sights and sounds of the Economist video. Indeed, the video succeeds in making the end of life, especially when there’s suffering involved, appear meaningless. Even if we can point out every logical fallacy committed in pro-euthanasia arguments, a broader question remains unanswered: what’s the purpose of my life when all I seem to be doing is wasting away in a hospital bed?

The success of the “death with dignity” movement can, paradoxically, be located in their appeal to our most natural, most fundamental human desire: to live. As the English Dominican Bede Jarrett observes,

We desire life. Even when, under stress of grief or failure or pain [or terminal illness], we cry out for death, it is only because our distress makes us realise how life is denied us… Life is indeed our desire.

What the Economist video plays upon are the conditions under which we are accosted by the great indignity that is serious, debilitating illness. It shows the grim reality of something entirely outside our control holding us prisoner and slowly squeezing the very life out of us. It’s an affront to our desire to live and have life more abundantly (whereas daily life with a debilitating illness seems to be only a cheap imitation of “real” [read: able-bodied, fully autonomous] life). Hence proponents’ appeals to “quality of life” arguments. Terminal illnesses are such an affront that many want to snuff life out for the sake of life itself, so terribly is it being violated.

So, to rephrase the Economist’s question, what would it take to live a life like the one they depict? I would struggle mightily. But that’s in part because there is something missing—both from the rhetorical, natural law arguments against euthanasia and from this video in favor of it. Something is missing on the wall.

There’s no crucifix.

If the wall is empty, so too is human suffering seemingly empty—devoid of meaning.

The cross is the fullest expression of the meaning that our suffering can take. If I had my eyes fixed on the cross all day, then I could live a life like this. Because it would be more closely conformed to Christ’s life, bound to the cross.

Christ came to redeem humanity—precisely by redeeming human suffering. He did not come to shield us from it, but to transform its meaninglessness. Pope St. John Paul II explains: “In bringing about the Redemption through suffering, Christ has also raised human suffering to the level of the Redemption” (Salvifici Doloris, §19). In our suffering, then, we become sharers in Christ’s redemptive suffering. As Pope Benedict observes, “It is not by sidestepping or fleeing from suffering that we are healed,” which is what physician-assisted suicide offers, “but rather by our capacity for accepting it, maturing through it and finding meaning through union with Christ, who suffered with infinite love” (Spe Salvi, §37).

The cross makes dying a process in which we are assisted by the Divine Physician. The medicine He administers is the medicine of immortality.

If the cross remains in view, the road to Calvary merges with the road to Emmaus: in our final agony, we encounter the Risen One. In the apparent senselessness of what the Economist video depicts, the Christian is able, by grace, to see a truly meaningful horizon open up. We exercise our right to die—our right to die in Christ—in accord with the Father’s will.

✠

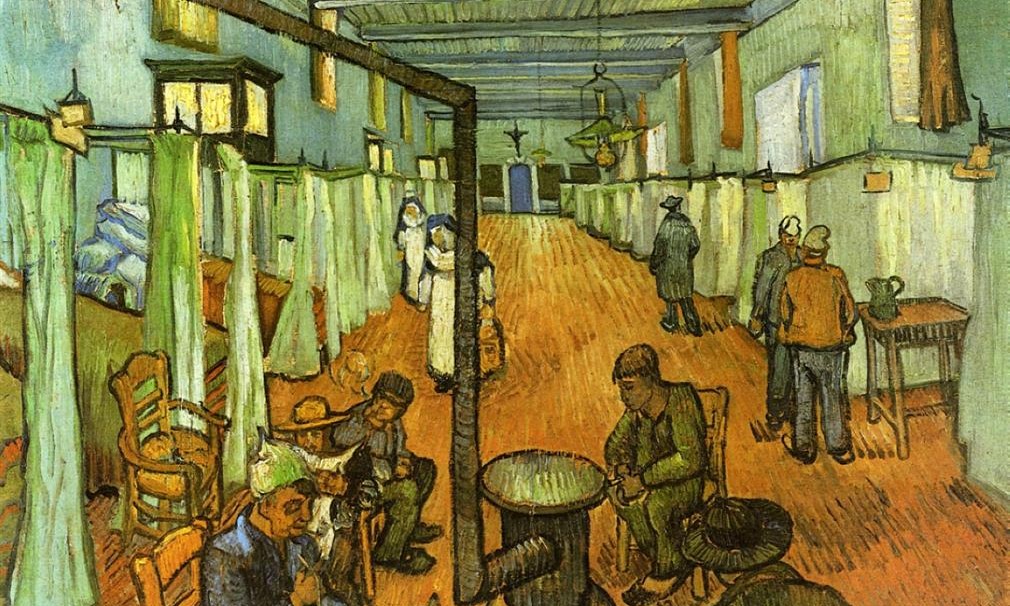

Image: Vincent Van Gogh, Ward in the Hospital in Arles