Last Friday an article by professional food developer Barbara Stuckey appeared in the “Life and Culture” section of The Wall Street Journal. Ms. Stuckey writes that, though she loves her job, she is “constantly frustrated by the unwillingness of most Americans to try foods that challenge their palates.” Americans, she says, tend to cling to their favorite bland foods, and these tend to be loaded with sugar. “Expanding our repertoire of foods isn’t just about exploration and new pleasures,” Ms. Stuckey explains, “It’s also the first step toward eating a broader, healthier diet.” Instead of simply bemoaning the problem, she provides practical, concrete steps to self-education that actually sound like they could be fun.

As I read the article, it occurred to me that her observations could also be applied to musical taste. Indeed, the metaphor of “taste” turns out to be very apt.

As children, we tend to regard all sweet food as good and anything with a hint of bitterness as bad. When I was a boy I thought adults were crazy or masochistic because they prized foods like asparagus, tart cranberries, and dark chocolate, or bitter drinks like coffee, beer, and wine. Of course, as Ms. Stuckey points out, many adults never diversify their tastes beyond their childhood predilection for sweetness, and this impairs their ability to enjoy a broader range of foods. Those, on the other hand, who have discovered more complex flavors usually don’t want to cover them up with too much sugar or fat.

Something similar applies in music. When we are young, we regard anything with a peppy melody or a foot-tapping beat as “fun” and “exciting,” while anything that is longer, slower, or without a drumbeat strikes us as “boring” or “gloomy.” As we grow up, however, we discover—or don’t discover—that other musical forms not only exist, but can offer a richer, more profound, and subtler emotional-intellectual experience. Just as food is more complex and interesting than “Sweet? Yum! Bitter? Yuck!” so music can elicit more complex and profound emotional states, such as sorrow with sweetness, or joy with solemnity.

One non-academic reason to educate our musical palate is the importance of music in the liturgy. The Second Vatican Council, in its Constitution on the Sacred Liturgy, says that the musical tradition of the Church “forms a necessary or integral part of the solemn liturgy” (Sacrosanctum Concilium 112). The Council Fathers specifically recommend Gregorian Chant as “specially suited to the Roman liturgy,” and they say that, other things being equal, “it should be given pride of place in liturgical services” (SC 112, 116).

Our difficulty in receiving this teaching does not arise from any special difficulty in performing the Church’s sacred chant. Indeed, much of the chant repertoire is rather easy to sing. Rather, it’s that chant has “flavors” that are challenging to our tastes. Note that this can be true even for accomplished musicians. Moreover, it isn’t just a post-Vatican II issue: swapping in sweet and catchy songs was widespread well before we added guitars to the mix.

The popes, both before and after the Council, have patiently exhorted us in this matter, but they haven’t issued many commands. They know from history, I suppose, that peoples’ ability to embrace unfamiliar music takes more than mere dutifulness. But, since they and the Council think it’s so important, what about trying Ms. Stuckey’s advice, adapted to sacred music?

What would that adaptation look like? We could begin by recognizing that there’s a time and place for every kind of music. Just because a musical style isn’t appropriate to the liturgy doesn’t mean we can’t enjoy it in other contexts—even other religious contexts. Next, we shouldn’t be discouraged if we don’t find traditional sacred music immediately appealing. As Ms. Stuckey says, “Experts in food neophobia—the fear of new food—have shown that it can take five to ten attempts at trying something before you reach the point where you don’t reject it outright.” It took me about that many tries until I stopped hating coffee, and more still before I really started to like it. But the ability to enjoy good coffee now makes me happier than if I had never bothered.

With these things in mind, how about trying these exercises:

1. Try listening to music that’s new and different to you. How about music from another culture altogether?

2. Find out what musical “modes” are. What do Miles Davis and Gregorian chant have in common?

3. Listen to modal music more often. It may be more familiar than you think. Many folk songs and some popular songs use modes other than those we most commonly hear, the major and the minor keys. Eventually, you might be able to tell the modes apart just from their “sound.”

4. Try “horizontal tasting” of sacred music. Start with what’s least inaccessible to you and try listening to it for a week. When you understand it better, you may find that similar music makes more sense. Do you avoid chant because you have a hang-up about Latin? Try listening to the Simple English Propers or the English chants of Gethsemani Abbey, Fr. Samuel Weber, or Fr. Columba Kelly. Afraid you’ll sound too much like monks? Find a good parish chant group, like Cantores in Ecclesia, and take them as a model of lay excellence in Gregorian song.

5. Instead of just listening, try singing, too! Ask yourself, “What might solemn rejoicing sound like?”

Thanks to the Internet, there are lots of free, easy-to-use multimedia resources. What is there to lose?

✠

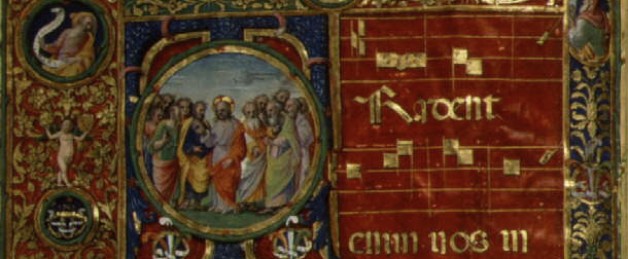

Image: a sixteenth-century manuscript with a chant beginning Tradent enim vos (Matthew 10:17).