“We do what!?” I thought. “Isn’t this idolatry!” But there it was “All, after genuflecting to the Cross, depart in silence.”

It was the morning of Good Friday, 2012. The deacons and I were sitting in the Sacristy reading through the rubrics in the new Roman Missal while preparing for the altar server rehearsal. Venerating the cross with a kiss during the service was familiar and understandable–but genuflecting to the cross? Weren’t genuflections an act of adoration reserved for the Blessed Sacrament? For God Himself?

I checked the General Instruction of the Roman Missal to make sure: “Genuflections and Bows: 274. A genuflection, made by bending the right knee to the ground, signifies adoration, and therefore it is reserved for the Most Blessed Sacrament, as well as for the Holy Cross from the solemn adoration during the liturgical celebration on Good Friday until the beginning of the Easter Vigil.” Well, that was that. A Genuflection signifies adoration, and here the Church asks us to genuflect to the cross—wracking us with an awareness of Christ’s passion, from Good Friday until the Easter Vigil.

Most Catholics seem to intuitively grasp that such adoration of the cross is not idolatry. But that didn’t stop a smart-aleck high school senior like myself from pressing the point. While I can’t remember their exact words, the deacons I was with did an excellent job fielding my objections. Their answer went along these lines, which I came across recently in Amalarius’s On the Liturgy:

And as I lie before the cross, Christ, who suffered for me, is inscribed upon my heart. I adore the power that the holy cross received through the Son of God, worshiping no created thing in the way that I adore God, but rather venerating it…. In body I lie prostrate before the cross, but in my mind I lie prostrate before God. (Amalarius)

Here we need to make a distinction. Following St. Thomas, images, like those of Christ and His cross, can be regarded in two ways:

First, as something in their own right. To adore an image in this way, simply as something carved or painted, is idolatry. It would be to worship a created thing in the way that I adore God.

Second, however, images can be regarded precisely as images—as representing something else. When a person reverences an image in this way, the act “does not stop at the image, but goes on to the thing it represents” (ST II-II, q. 81, a. 3, ad 3). And when this image is of Christ, St. Thomas does not shy away from maintaining that the reverence given is an act of latria, the same word used for the adoration of Christ himself (ST III, q. 25, a. 3, corp.). The Council of Trent affirms that “through these images which we kiss and before which we kneel and uncover our heads, we are adoring Christ” (DH 1823).

More than simply piquing my curiosity, the new rubrical change had a gradual, but profound effect on my spiritual life. With the help of St. Thomas, I came to experience and to see the fittingness (ST II-II, q. 84, a. 2) and even the necessity (ST III, q. 61, a. 1) which bodily acts of worship have in conforming us to God.

For the Son of God emptied himself in order to be visible to men. On the day when we kiss the cross, he was humbled for our sakes before the Father unto death, even to the death of the cross. If we are to imitate his death, we should also imitate his humility. And so we lie prostrate before the cross to express our unmoving humility of mind through the posture of our body. (Amalarius)

✠

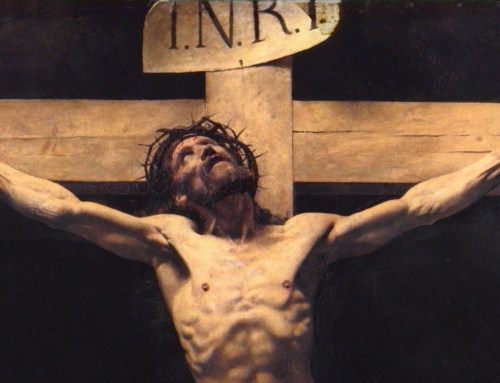

Image: Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)