In his book The Machine and the Garden the social and political philosopher Leo Marx describes the cultural dynamics of the United States as an outgrowth of the pastoral tendencies of the Western mind. Beginning with the Greeks, the romanticism of nature has resonated deeply in Western culture. While taking many different forms, this theme has always evoked a longing for harmony – a return to nature that can alleviate the burden of man-made sufferings. It was the Roman poet Virgil who first placed this theme in political context, defining the “middle landscape” as that balance-point between the corruption of the city and the savagery of the wilderness. The pastoral wisdom of the middle landscape provided a check on the machinations of human society, holding the religious, social and political constructs of a given culture accountable to the natural, to the real.

When the accumulated weight of human tragedy and failed social projects came to weigh upon the European mind during the Enlightenment, Marx argues that the cultural resonance of the pastoral ideal came to alight on a fresh subject; turning their hopes towards the wilderness of the Americas, many European thinkers came to believe in the possibility of a renewed middle landscape. This sentiment would be taken up by American thinkers and writers such as Hawthorne and Thoreau, who extolled the natural beauty of the American landscape as a refuge from misguided human progress; in this much their outlook is decidedly hopeful. Perhaps the middle landscape of rural America would serve as a source of humanistic renewal for society.

In the twentieth century, however, American humanism would be emptied of much of its self-confidence. The results of this shift can be felt in certain strands of pastoral writing that emerged in early twentieth-century America.

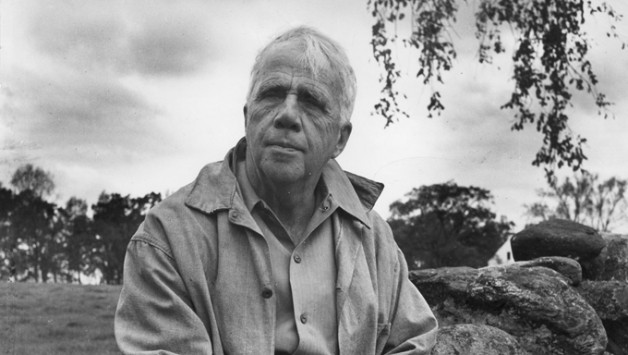

The poetry of Robert Frost falls clearly within the genre of American pastoral literature – Frost writes from a farm in New Hampshire, bringing the clarity of his rural American experience to bear on the human condition. The interplay between wilderness, human structures, and middle landscape is continually palpable. Frost’s pastorale is darker than its nineteenth-century precursors, however, and noticeably less confident in the middle landscape as a source of perennial renewal.

In his 1928 poem, “The Last Mowing,” Frost seems to offer a glimpse into his own understanding of the state of the American pastorale.

There’s a place called Faraway Meadow

We never shall mow in again,

Or such is the talk at the farmhouse:

The meadow is finished with men.

Then now is the chance for the flowers

That can’t stand mowers and plowers.

It must be now, through, in season

Before the not mowing brings trees on,

Before trees, seeing the opening,

March into a shadowy claim.

The trees are all I’m afraid of,

That flowers can’t bloom in the shade of;

It’s no more men I’m afraid of;

The meadow is done with the tame.

The place for the moment is ours

For you, O tumultuous flowers,

To go to waste and go wild in,

All shapes and colors of flowers,

I needn’t call you by name.

When a field is continually cultivated without rest, it eventually reaches a point of exhaustion – a point at which the soil has no sustenance left to give. Its infertility being acknowledged, the farmer simply moves on to a fresh patch of land, carving a new field out of the wilderness. Frost has no concern for these new possibilities, however. His pastorale is not one of hopeful expansion. His focus is instead on the inevitable return of the wilderness. In light of this the middle landscape shrinks and can only claim a fleeting moment, before the return of the trees. What is the human project that Frost is finished with, here symbolized by the ‘mowing’ of the field? There is no immediate clue here, but a familiarity with his other works leads one to believe that it is organized religion, specifically Christianity.

To speak of Frost as an atheist or agnostic is a mistake – references to God pepper his work. And yet he speaks of God in wary and uncertain terms, betraying a kind of secular humanism that is watching its back. In the absence of organized Christianity, what is a man to make of God? Is He friend or foe? Will He allow me to live as I choose, only to punish me with cosmic cruelty in the end? Will He even notice if I repent? What would it even mean to do a thing like that?

These days, there is much talk in the Church of a New Evangelization – everyone concerned acknowledges that there is a pressing need to preach the Gospel afresh to a secularized world. But to whom will we be preaching?

Although published almost one hundred years ago, many of Frost’s poems still speak strongly to our present cultural situation. Beneath the bluster of the ‘New Atheism’ and every last post-modern subjectivist excuse, there seems to lie a deep existential vulnerability in modern man, who finds himself trapped between his rejection of the past and the inevitable advance of the wilderness. Although he sees no certain future in his humanism, a return to previous religious structures seems impossible: “We never shall mow it again”.

Is there hope that a post-Christian society can recover its faith, once lost? When preaching in Bavaria in 2007, Pope Benedict noted that secular persons “place little trust in the future. Yet the earth will be deprived of a future only when the forces of the human heart and of reason illuminated by the heart are extinguished – when the face of God no longer shines upon the earth. Where God is, there is the future.” There is no simple response to the troubles of the present, but perhaps we do have an opportunity to preach now what has always been true: whether our humanism is filled with Enlightenment optimism or post-modern uncertainty, it is never our own projects – pastoral or otherwise – which give us hope for the future. It can only be Christ himself; Christ who is present to us now, even in our despair or fear – present to us from the depths of the cross.

Image: Robert Frost