Do you enjoy Victorian Gothic preternatural mystery novels, but wish they had a bit more metaphysical and theological grounding in reality? Are you tired of the protagonist who becomes the king of the werewolves or falls in love with the 3000-year-old vampire? If so, then Brother Wolf and its predecessor A Bloody Habit may be the books you are looking for. In this newest installment by Eleanor Bourg Nicholson, Fr. Thomas Edmund Gilroy, O.P., D.C.L. (Doctor of Canon Law), Vampire Slayer returns to lend a hand to his Franciscan brothers in wrangling werewolves.

The protagonist in Brother Wolf is no longer London lawyer, John Kemp, but Athene Howard, the daughter of a renowned Parisian professor. In pursuit of Jean-Claude, Athene and her father join up with:

Sister Agatha, a Dominican nun sometimes known as Eloise

Isabel, a Dominican postulant sometimes known as Sister Magdalene

Sir Simon Gwynne, an English nobleman

and Fr. Gilroy, the itinerant expert of all things preternatural

Jean-Claude is Isabel’s twin brother and also a Franciscan werewolf who is on the lam and must be brought back before he gives in to his bestial urges and must be put down instead. Set in 1906, about 5 years after the adventures of the first novel, Brother Wolf takes us on a journey throughout the continent, principally focused in northern France and Belgium, as our investigators make their pursuit.

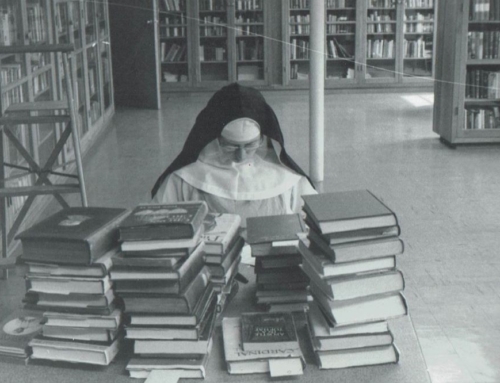

Nicholson’s acquaintance with Dominicans is evident and she accurately conveys a number of our eccentricities. Athene is not even Catholic and there is an undercurrent of bewilderment as she encounters not only Papists, but ones dressed in white robes and black capes with a proclivity for bad puns. Of course, given Athene’s extensive education, where else would she turn to familiarize herself with her new companions than the Summa Theologiae? Nicholson presents the first summary of the Summa that I have ever seen in a novel, listing the major themes in order, even if she doesn’t quite make it through the entire work (158). This is also the occasion of perhaps the most unbelievable claim in the whole book: Athene manages to make her way through the entire Prima Secundae in only a single day. As a point of reference, we spend an entire semester on the first pass through this section of the Summa at the Dominican House of Studies.

Athene’s philosophical background supplements her theological assessment of preternatural creatures and their nature. For example:

[Fr. Gilroy] “The evil person, habituated to vice, does not will any differently. He chooses evil. This makes him an object of blame. The wanton person has been habituated to vice as well but to the extent that his will has become irrelevant. Second order desires have no effect. He is compelled in the continuation of his vicious habits. That makes him an object of pity.”

[Athene] “So we stake vampires and seek to rehabilitate werewolves?”

He smiled. “We dispatch demonic beings and seek to save their victims and, if still living, their minions.”

“Is this not a form of theological hair splitting?”

“It is a complex business,” he acknowledged. “Scholastic precision and pastoral judgment are of vital importance.” (283)

In this dialogue between Fr. Gilroy and Athene, Nicholson provides a refreshing contrast to the many modern depictions of vampires and werewolves by appropriately distinguishing them according to principles of human action that can be found in the Summa. Sin still requires the voluntary action of an individual even if certain conditions present greater temptations toward that sin. All of us have our personal proclivities toward specific sins which make us more likely to fall into them. Lycanthropy, the curse of the werewolf, is this proclivity taken to the extreme, The werewolf is one in whom the wounds of original sin have been rent wide. His passions are more violent and are accompanied with bestial transformations that manifest how these passions war against his reason. Much like we all involuntarily receive these wounds of original sin, the werewolf is infected by his curse even without having desired the condition. Yet he still has the ability to act or not act on them.

The vampire on the other hand has voluntarily chosen his condition. The true vampire is distinct from his thralls who are in some form or another under his sway. The vampire is no longer a living being, but a damned soul puppeting a dead body. The will of the vampire has been fixed in death just as the wills of demons were fixed at their fall, neither can make a choice for good anymore. There is no redemption for evil spirits or those who have died in sin, but no one still alive is beyond saving; Athene has reasoned aright, we stake vampires and rehabilitate werewolves.

The most valuable lesson to be gleaned from these novels is how God’s providence is at work in all men and women. Athene does not have the most important role in the unfolding drama. All of her companions are stronger, more experienced, or more pious. Athene’s part is nonetheless necessary even if others are larger. She is so appealing of a heroine because hers is a heroism that any of us could aspire to. Athene does not triumph because she has discovered secret knowledge or recovered an ancient power. She triumphs because she does not succumb to the seductive temptations of an evil more intelligent and powerful than her. As with any spiritual battle, her warfare is fought within her own soul. Ultimately, Athene’s is a simple heroism of persistently searching for truth and remaining staunchly loyal to her friends in times of trouble and distress.

✠

Image: Illustration by Mont Sudbury from “The Werewolf Howls” in Weird Tales (November, 1941. Vol. 36, no. 2, pg. 38).