When Julius Caesar, at the age of 33, considered the achievements of Alexander the Great, he wept. His sighs and tears did not come as a result of mourning or fear for his own life, but from a sobering recognition: Alexander had conquered the world before the age of 33 and yet he (Caesar) had done nothing remotely similar, nothing that would warrant remembrance by future generations in the same amount of time (see The Life of Julius Caesar, by Plutarch). What, then, was the worth of his life? Who would remember an average Roman governor of Spain? Who would remember the name of Caesar?

This line of questioning seems to be a common experience. At some point in our lives, we all seem to ask the same question: Have I made a difference? And again: What do I have to show for the past year, decade, lifetime? This type of questioning can lead people to a “mid-life crisis”—radical changes in an effort to be remembered.

Other, related thoughts can haunt us: A year after my death, will anyone remember me? A decade after … a century after? Or will my legacy, my name, be forgotten?

This universal desire to be remembered can also be seen, as a photo-negative, in an ancient Roman practice: the damnatio memoriae. This punishment was created specifically for tyrants and enemies of the state. The Roman government wouldn’t just execute the culprit—they would erase him from history. Any influence he may have had—buildings he built, statues depicting him, laws he issued, paintings of him, all of it—was erased, destroyed, rescinded. The effects of thousands of years were accomplished in a single edict. The person’s entire heritage and life were effaced such that it was as if he never was…

We might shudder at the possibility of our erasure from reality. But it is instructive for us to consider the idea all the same. What is at the root of this desire to be remembered? At its root, ultimately, is a desire to be recognized, known, and loved. As Christians, we have been assured that God, who is our loving Father, will never forget us. We are told in the book of Isaiah that, even if a mother were to forget her child—which is unthinkable—even less imaginable is that God would forget us (Isa 49:15).

Since God is eternal and he will never forget us, someone will always remember us. In fact, we are told that those who are predestined for heaven have their names said by Christ before the Father and written in the book of life (Rev 3:5). The content of this book, the definitively-written names of those predestined to be saints, can never be erased. No imperial edict, no amount of paint, no lack of worldly achievement, can effect a damnatio memoriae for God’s beloved children.

Therefore, as God’s beloved, we glory not in temporal accomplishments but rather rejoice that our names are written in heaven. We don’t have to worry about our accomplishments, successes, statues, memorial buildings, or tombstones. For we know that we are remembered by God and that the names of the saints can never be blotted out of the book of Life. We no longer have to weep when we encounter that statue of Alexander, or when we hear of another breaking our high school sports record, or when we learn of another getting the promotion we wanted. No. The Christian should have no mid-life crisis (as did Caesar), because his hope is ever new and ever young.

Lastly, and most encouragingly, not only do we know where the names of the saints are written, we also know the material from which the book is made. Our names are inscribed upon a material more permanent than any stone, silver, bronze, or paint. It is a material impervious to the passing of time. It is the most lasting of inscriptions … written upon the very flesh of the God-man.

“See, upon the palms of my hands I have engraved you” (Isa 49:15).

✠

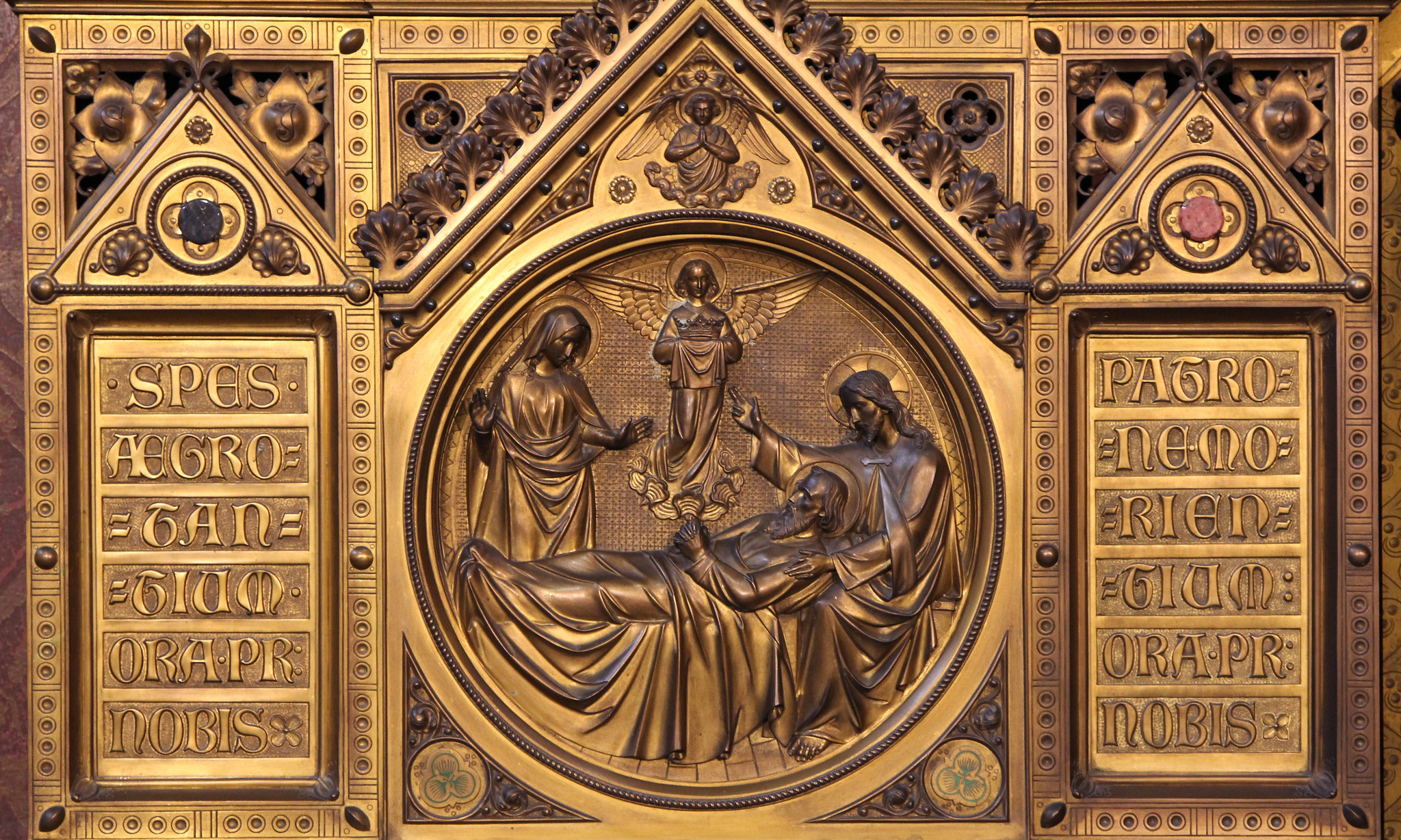

Photo by Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P. (used with permission)