Ivan Ilyich saw that he was dying, and he was in continual despair. In the depth of his heart he knew he was dying, but not only was he not accustomed to the thought, he simply did not and could not grasp it. The syllogism he had learnt from Kiesewetter’s Logic, “Caius is a man, men are mortal, therefore Caius is mortal,” had always seemed to him correct as applied to Caius, but certainly not as applied to himself. That Caius—man in the abstract—was mortal, was perfectly correct, but he was not Caius, not an abstract man, but a creature quite, quite separate from all others.

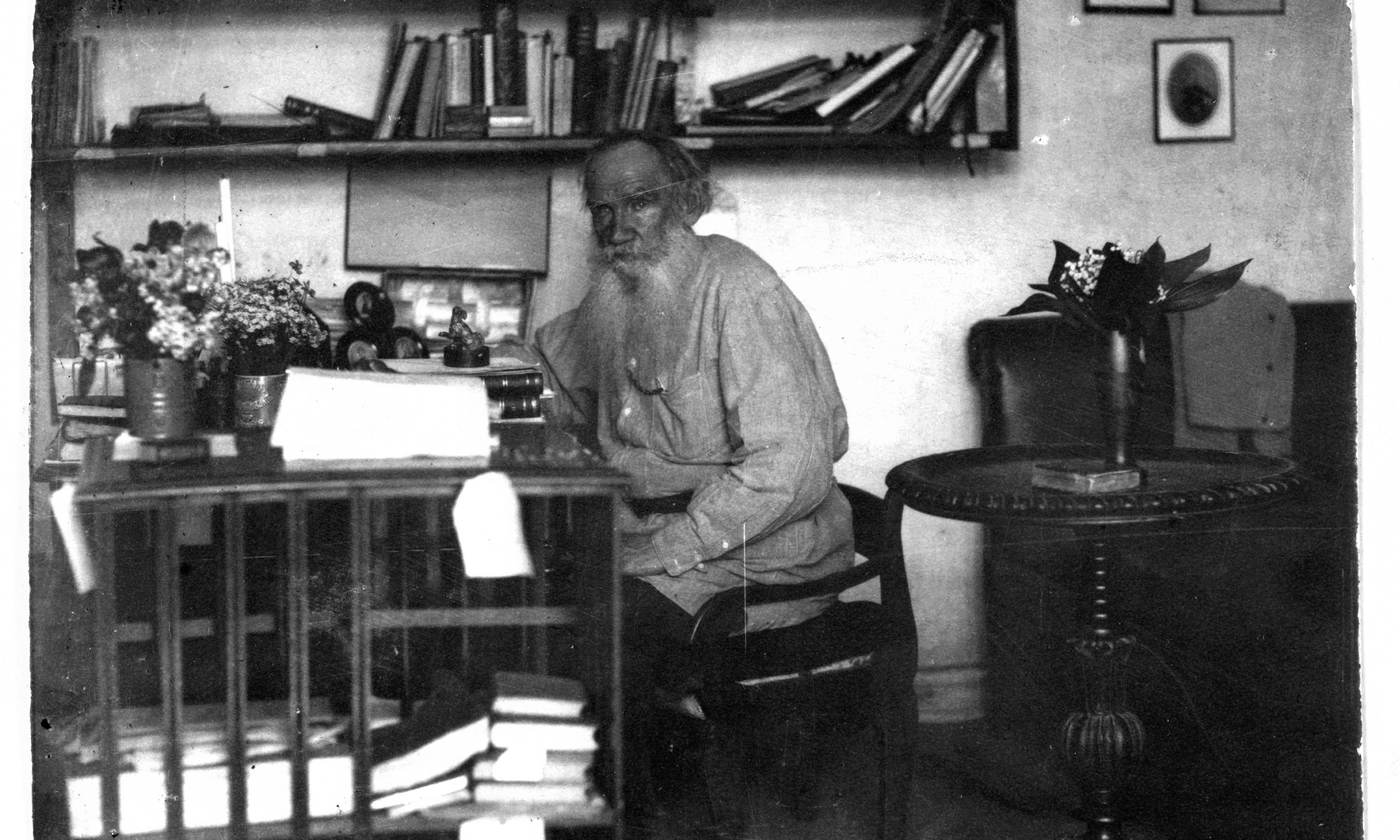

—Leo Tolstoy, The Death of Ivan Ilyich

It’s short, and it’s all about death. Maybe that’s why we read it in high school.

Tolstoy’s classic novella about the slow, terminal decline of an ordinary, middle-aged lawyer continues to fascinate both young and old, though in different ways. In the young, Ivan Ilyich tends to elicit a certain amount of pert amusement or dignified scorn. He’s so obviously a fool, a hypocrite, and a coward, and Tolstoy so expertly probes the depths of his folly, that it’s easy to sit back, analyze, and, in general, hug tight the warm fuzzies of moral or intellectual superiority. Having done as much myself, I won’t begrudge others the opportunity.

Later in life, however, when we come back to the story, we find something unaccountable has happened. Somehow, the shoe has gone to the other foot. Somehow, we have become Ivan Ilyich. That ordinary, middle-aged fool now bears a striking resemblance, if not in all respects, at least in certain definite and disturbing ways, to me. The wry smile fades. Self-satisfaction takes to its heels. We’re sorry for our smugness—and we’re sorry for Ivan Ilyich. We start reading the story in a whole new light—the light of contrition and compassion.

Like most of us (when it comes right down to it), Ivan Ilyich can’t believe he has to die. He’s tormented by the fact, and he can’t understand, since he has always done what is “proper” and “correct,” why this horrible thing must happen to him. More than once, though, he entertains what seems to him an impossible notion: that his death would at least be comprehensible and bearable, if only he could bring himself to admit that he had not led a good life.

It occurred to him that what had appeared perfectly impossible before, namely that he had not spent his life as he should have done, might after all be true. It occurred to him that his scarcely perceptible attempts to struggle against what was considered good by the most highly placed people, those scarcely noticeable impulses which he had immediately suppressed, might have been the real thing, and all the rest false.

This idea, which at first Ilyich finds so “morbid,” is reinforced by the disgust he begins to feel for the very people with whom he used to live and work. Suddenly, the sophisticated civility that bound him to them, and them to him, becomes an impregnable barrier to all meaningful communication—a mask for their selfish refusal to suffer with a dying man:

The awful, terrible act of his dying was, he could see, reduced by those about him to the level of a casual, unpleasant, and almost indecorous incident (as if someone entered a drawing room diffusing an unpleasant odor), and this was done by that very decorum which he had served all his life long. He saw that no one felt for him, because no one even wished to grasp his position.

Ilyich longs to be comforted and petted “like a sick child,” but when a respected colleague comes to visit, he prefers to assume “a serious, severe, and profound air,” and “by force of habit” delivers his judgment on some legal matter, “stubbornly insisting” on his opinion.

Only one person is able to console him—the peasant Gerasim, his servant. Unlike everyone else, whose insincerity drives Ilyich to the point of madness, Gerasim frankly acknowledges the imminence of his master’s death, and sees it as something in which he himself must share. He willingly stays up whole nights, supporting his master’s legs on his shoulders, and, when questioned, replies cheerfully, “We shall all of us die, so why should I grudge a little trouble?”

Toward the end, a priest comes to hear Ilyich’s confession. The gift of divine mercy, along with the contrition it elicits, brings him a measure of peace, but, interestingly, it’s not until the hour of his death that this grace fully flowers, enabling him to extend the mercy he himself has received to those around him:

. . . with a look at his wife he indicated his son and said: “Take him away . . . sorry for him . . . sorry for you, too . . .” He tried to add, “Forgive me,” but said “Forego” and waved his hand, knowing that He whose understanding mattered would understand.

Contrition, compassion, mercy—these, Tolstoy seems to suggest, are the graces without which death becomes incomprehensible and unbearable. During this month of November, then, when nature itself joins the Church in bidding us have a “seasonable regard” for our mortality, let us take such wisdom to heart. And let us remember that those who strive to know and love God in this life, need not fear meeting him in the next.