Do you ever skip the introductory pages of a book you are reading? If so, STOP IT! You could miss one of the best parts, the epigraph. You know, that short quotation which the author has carefully selected to summarize, introduce, or preface his own work with. It is a tip of the hat to an older author, a humble recognition in the face of past genius, and a claim that this work you, the reader, are now holding stands in a tradition that almost makes the current volume at best superfluous, at worst supercilious. Almost.

Need some encouraging examples? Here are some of my favorites, taken at random from my bookshelf:

For evidently you have long been confident, what you really mean when you use the expression “being”, but we however, who formerly thought we understood this expression have now become confused (from Heidegger, Sein und Zeit).

Martin Heidegger opens his magnum opus with this quote from Plato’s Sophist summarizing the whole point of the book: the question of being, what it means “to be” and all its existential ramifications.

Or how about this one:

Catch only what you’ve thrown yourself, all is

mere skill and little gain;

but when you’re suddenly the catcher of a ball

thrown by an eternal partner

with accurate and measured swing

towards you, to your center, in an arch

from the great bridgebuilding of God:

why catching then becomes a power–

not yours, a world’s (from Gadamer, Truth and Method).

Hans-Georg Gadamer uses this beautiful poem from Rainer Maria Rilke to introduce his project of understanding texts, ourselves, and the world by listening attentively to the traditions in which we find ourselves, letting those ancient voices challenge our own naive modern understandings.

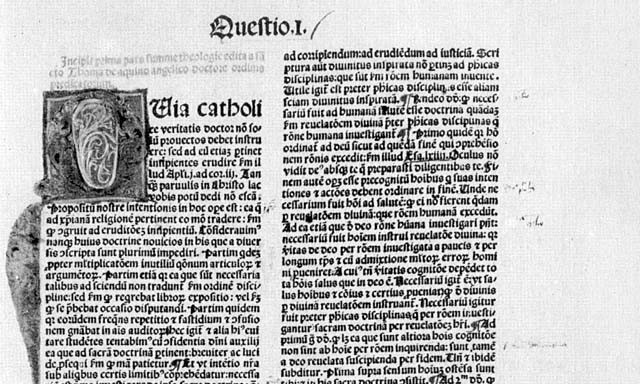

German philosophers are not the only ones playing this game—which brings me to today’s feast: St. John Damascene. You see, St. Thomas Aquinas opens his Secunda pars, the second part of the Summa Theologiae, with a quote from the Doctor Assumptionis:

Since, as Damascene states (De Fide Orth. ii, 12), man is said to be made in God’s image, in so far as the image implies “an intelligent being endowed with free-will and self-movement”: now that we have treated of the exemplar, i.e. God, and of those things which came forth from the power of God in accordance with His will; it remains for us to treat of His image, i.e. man, inasmuch as he too is the principle of his actions, as having free-will and control of his actions. (Prologue, ST Ia-IIae)

After 119 questions on God and creation, the Summa turns to that most special of all creatures, man, who, like God and unlike other material creatures, has free-will and is able to move and motivate himself to good actions. The next 303 questions will outline those actions in majestic manner: the passions, habits, virtues, vices, gifts, beatitudes, law, grace, and the forms of life, just to give the baldest of summaries of this masterpiece. Man is a “micro-creator,” a being endowed with godlike powers to spread the reign of God in heaven to all creation.

But the incongruity between the vision of Aquinas and the dreariness of present reality is all too apparent. Thanks to sin and selfishness we are often not masters of our own movements. We use our free will not for the common good but for our own apparent goods. We become, if the word has any meaningful use, “micro-aggressors.”

This, of course, is where the genius of St. Thomas’ epigraph appears; the line from Damascene not only points from the Prima pars to the Secunda pars, but beyond it to the Tertia pars. For the word “image” conjures up the hymn to Christ in St. Paul’s First Letter to the Colossians:

He is the image of the invisible God, the firstborn of all creation; for in him all things in heaven and on earth were created, things visible and invisible, whether thrones or dominions or rulers or powers—all things have been created through him and for him. He himself is before all things, and in him all things hold together. (Col 1:15-17)

Christ is the true image of the Father, the God who became man in time for all times to show us the way to be human and the way back to our Father in Heaven. Our image-hood is renewed in Christ and is maintained by the sacraments of the Church, those moments of supernatural contact with Christ himself.

St. Thomas’ epigraph is an epigraph for Advent, a pregnant line from the tradition that reminds us about our origin and destiny in Christ. The vision of a human life fully lived is not beyond our grasp; it is no idealistic vision, German or otherwise. Damascene reminds us that God took the first steps, as usual, in the work he began and will finish, all of which we celebrate over the course of a few short weeks.

And if you are looking for a Lenten epigraph for meditation later, don’t skip the opening of Fyodor Dostoevsky’s The Brothers Karamazov. The epigraph comes from a very credible author.

✠