At 67, insight trumps muscles.

So I thought to myself as I watched Escape Plan the other night. The two action movie paragons, Schwarzenegger and Stallone, shared the screen in this film about an escape from a perfectly designed prison. Without pretending to review the movie or its artistic merits—as an incorrigible fan of cheesy action movies, I am rather blind to their faults—there is an element worth noting here.

These ’80s action heroes have long since peaked physically: Conan the Barbarian and Rocky are now more than 30 years old. So what is left for them to do? Why not cede the stage to Christian Bale and Jason Statham for Escape Plan?

I would like to propose a slightly implausible reason contained in the film itself: Stallone has become primarily a “watcher of men” (Job 7:20), and not simply a killer of them in the older character he plays in this movie. He spends most of the scenes not brawling or shooting but rather studying: the routine of the guards, their characteristics, the warden, the religious motivations of his fellow prisoners, etc.

When the raw physicality of youth fails, other powers come into the foreground and take precedence in the human person. Cicero wrote about the difficulties of old age, but he testifies to its value:

The great affairs of life are not performed by physical strength, or activity, or nimbleness of body, but by deliberation, character, expression of opinion. Of these old age is not only not deprived, but, as a rule, has them in a greater degree. (De Senectute, par. 6)

Cicero assumes that virtues of the mind have been at least minimally present in the youth all along, but they acquire a new importance when the body weakens. Yet our cultural milieu rejects this weakening as a foolish concession to nature. The quest for perpetual youth is on display everywhere: at drugstores, on billboards, in gyms, etc. This is an understandable desire, but ultimately an unnatural course for human life. To be young with bodily strength forever is impossible. Cicero points out “control of the passions” as one of the fruits of older age. To finally have self-mastery is most definitely worth being a little slower in movement. The Church has always agreed with Cicero on this one, and ranked the goods of the intellectual soul over the goods of the physical body. Maturity is the integration of the two and old age involves the ascendancy of the soul.

From my vantage point in my twenties, I can only agree that it would be ideal to have the vigor and vitality of 26 paired with the wisdom and insight of 76. But as an older priest in the province reminded me a few months ago: “I don’t think it works that way.” It can seem like a tragic trade-off. The saying “youth is wasted on the young” is just another articulation of this desire to have both. But there is a natural progression. It is applicable, as we’ve been considering it, in the life of nature, but also in the life of grace. The Christian soul develops integrally with our natural lives: training and strengthening in youth, appreciation and longing for the sight of God at the end.

To go back to the movie, Stallone and Schwarzenegger are trapped in a prison deep below the surface. They are outnumbered by guards, hemmed in by the strictures of prison life, and cut off from outside support. They need the intellectual virtues, not simply the physical or martial ones, to escape. It is a curious contrast with their earlier films, where (occasional strategic thinking notwithstanding) the amount of munitions or punches is the determining factor. The sight of God Himself in the Beatific Vision is the conclusion, the goal, of our life here. Analogously, it takes physical prowess (with grace assisting at every step) to get to the view, but like our heroes getting to the surface of the prison, our reason and the accumulated wisdom of the years will serve us in better stead than raw force.

✠

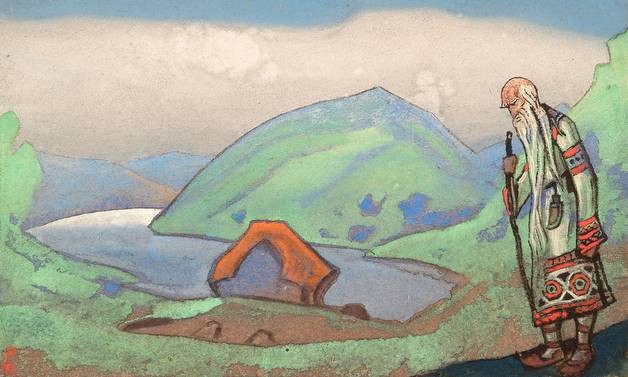

Image: Nicholas Roerich, The oldest, the wisest