At first, I simply wanted to read some good books. The fact is, I hadn’t kept up with reading literature since I left high school English classes behind. There was a novel or two here or there when I was home on vacation but it was pretty sporadic. It’s not that I didn’t see the value of the classics of literature; I just never set aside the time to read them between my studies in math and science and a good bit of time wasting on the side. When I arrived at the novitiate, where there was limited access to TV and the Internet, the things that had previously been major temptations to waste time were, thankfully, no longer an option. I decided that when I wasn’t occupied in the work, prayer, or study of the novitiate, I would spend some time catching up on reading good books.

Of course, there are a lot of good books out there, and it can be hard to figure out where to start. I thought the most logical place to start was at the beginning, with the classics of ancient Greece. So much later literature makes references to and assumes familiarity with Greek literature that it seemed reasonable to get familiar with those first. And yet, looking back, this is where the reasonable started to get a little irrational. If reading some of ancient Greek literature is good, then reading all of it has to be even better, right? By the end of the novitiate, I had read the Iliad and the Odyssey as well as all of the extant tragedies and had thrown in the comic plays for good measure.

This is just one example of my proclivity towards completionism. The desire to finish what you start is perfectly commendable, and there is much to be said about being thorough, but completionism takes it a step further. Having achieved some particular good and seen its value, completionism is the desire to experience every related good without exception. It’s a type of perfectionism aimed at some finite set of tasks with the promise of an amazing sense of accomplishment waiting at the end. Unfortunately, this sort of perfectionism often extends only as far as the checklist, not necessarily to the individual task. While I actually read every word of every extant Greek play, I can’t claim that I understood or appreciated them fully. What’s more, while there is undoubtedly some value in each of these ancient plays, there is a reason none of my classmates, who were much wider read than I, had read all of them. If the true goal is to read good books, then the Greeks can’t all be ignored, but to claim that even the least of the tragedies is better than anything else written in the last 2500 years is absurd.

When some present task, even if originally desired for something greater, gains an over-inflated sense of importance, it both clouds our judgment and twists the task itself. I had turned my noble goal of immersing myself in good literature into the chore of reading this particular set of forty or so plays whether I was enjoying them and appreciating them or not. Now, I don’t regret having spent time with these classics, although I do think I could have gotten more out of them if I approached them differently.

This ability to twist a good act into something lesser, even something damaging, is a real danger and can creep into many of our moral decisions. Even when we know that our true goal in life, our ultimate good, is to be happy with God forever in paradise, we can often lose sight of that goal for the particular task at hand. In a sense this is perfectly normal because the task at hand often needs a good bit of attention. The danger is when we inflate the importance of a particular task, even doing some good act or avoiding some bad act, such that we confuse it for the ultimate end itself.

When we begin to think that being a good person means completing certain tasks and following certain rules, we forget why we should be doing them at all. God wants us to be happy, and part of our being happy will, of course, involve doing certain good tasks and avoiding certain evils. Yet we should do these things not because they are part of some grand to-do list, but because we know that they are what will make us happy and, with the help of His grace, lead us to eternal happiness.

✠

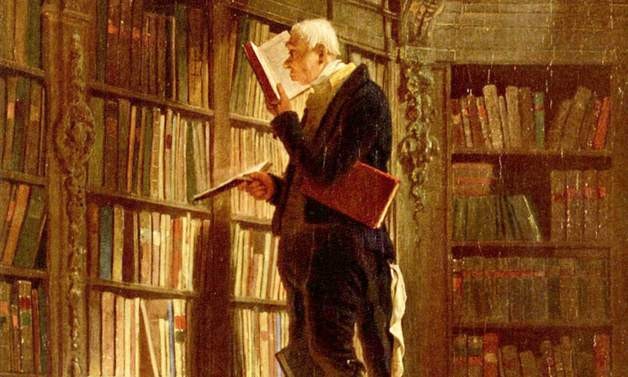

Image: Carl Spitzweg, The Book Worm