According to C.S. Lewis, Ronald Knox was “possibly the wittiest man in Europe.” But let’s not hold that against him. For one thing, he could hardly help it. For another, his wit is so understated, so self-effacing, so clearly aimed at pleasing rather than impressing, we can detect in it none of those offensive qualities which Americans typically associate with clever people. He comes across as entirely natural and unassuming, gracious and charitable.

Indeed, his leisurely, easygoing style, which more than a few in his day thought unsuitable in a clergyman, has induced some to regard him as ultimately superficial—a brilliant man whose charm got the better of him and who therefore never lived up to his full potential. In fact, however, the more one reads him the clearer it becomes that, underneath it all, Knox was both serious and deep. Perhaps this is what one of his contemporaries was driving at when he described him, somewhat unfairly, as “a sad little man with a wry smile.”

These contrasting qualities are certainly evident in Knox’s autobiographical work, A Spiritual Aeneid, in which he recounts his journey from Anglicanism (first evangelical then tractarian) to the Church. Knox, it seems, had a horror of taking himself seriously, and so he delights in sketching the course of his religious development by means of amusing little vignettes, such as this scene from his childhood:

One or two boys at school were Catholics; it never occurred to the rest of us to be interested in their beliefs. But I remember once hearing one of them taunted (in a fit of anger) with being a Papist; I remember, too, quite distinctly the sense of embarrassment and horror with which we turned on the railer and kicked him, by way of inculcating manners. There was no question of tolerance; we were simply in an agony of good breeding.

Then there are the occasional, unexpected volleys of satire, such as this, on biblical criticism:

I wrote an examination of Schweitzer’s assumptions in the form of a pamphlet which I had been asked to write for a series; it was not accepted, being probably badly written as well as over-orthodox. But my doubts about the Higher Criticism were redoubled, I fell into a horrible skepticism, in which at times I lost all lively faith in the existence of Q.

As the book proceeds, however, the attentive reader begins to realize how serious Knox was, as well as how much he gave up, humanly speaking, in order to enter the Church. We also realize what a prodigious work ethic he had—of course, one would expect as much from a man who single-handedly translated the entire Bible—and this is all the more notable for not having dulled his sense of humor. But most impressive of all, perhaps, is the humility with which he became Catholic, and the gratitude he showed toward both Anglicans and the Church once he had become Catholic.

It would have been easy for someone of Knox’s social and intellectual standing to see himself as a gift to English Catholicism and, indeed, to the Church at large—to assume the grand role of Defender of the Faith in a Protestant country. But, while he certainly appreciated the chance to work for an unpopular cause, and even regarded the number and variety of the Church’s enemies as evidence of her divine founding, he also believed that a militant or controversial attitude was entirely out of place in a person moving toward conversion. He writes,

It is wrong to join the Church because the Church seems to you to lack support which you can give. You must come, not as a partisan or as a champion, but as a suppliant for the needs in your own life which only the Church can supply—the ordinary, daily needs, litus innocuum, et cunctis auramque undamque patentem.

Upon entering the Church, Knox was pleasantly surprised to find life within its walls more liberating and, as it were, more spacious than life had been outside. Something of this feeling is captured in the Latin phrase just quoted, taken from Book VII of the Aeneid. What Aeneas and his companions had sought on their journey, Knox found in the Church: “a friendly shore, with water and air free for all.”

✠

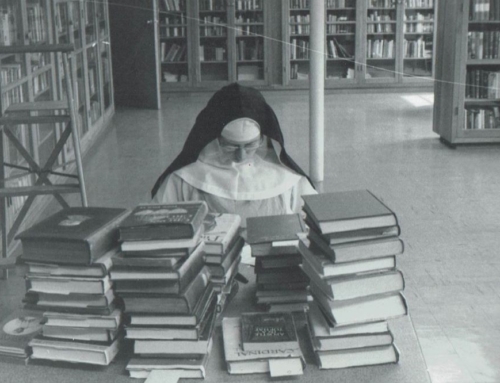

Photo by Katherine McCormack