His aunt had just passed.

She was young, only in her 30s, and with two small children. She had cancer. It could have been treated, but the doctors found it too late.

A group of us were in the living room of a mutual friend. Dim, warm light flowed from a few lamps, illuminating the dark wood paneling before being lost in the darkness of the vaulted ceiling. We were talking and laughing, having a delightful time.

Then he walked through the door. A rush of winter air scoured the room before he could close it behind him. He was very late. Some friends had already gone home for the night.

One friend razzed him, and another quipped how hard he had to fight to save him some pizza.

Then, standing just past the threshold, he dropped the news on us.

Everyone was quiet, and he didn’t move. Somebody said, “I’m so sorry, man.”

Then he shot his gaze toward me. He was normally a very meek and soft-spoken man, but in this moment a confused mix of sadness and anger flared up into indignation—all he managed to get out was, “She was good! She went to Church every Sunday! What kind of God lets this happen?”

Now everyone was quiet again. Taken in the abstract, my friend’s question is not hard to answer: God is infinitely good, so he didn’t make death and takes no delight in it. We humans are not infinitely good, so it is possible for us to sin. In fact, we did sin, and so death entered the world (Wis 1:13-16). God could have stopped us from sinning, but he didn’t. He permits evil and death in his creation because by his infinite power he can “bring good even out of evil” (STh I q. 2, a. 3, ad 1).

But I didn’t say any of that. It is all true, but doesn’t really answer my friend’s question. He doesn’t want an abstract explanation of the possibility of death or evil. He wants to know why God let his aunt die tonight.

Why did God permit this particular evil? God could have saved her—why didn’t he? We don’t know. The particular judgments of God’s will are inscrutable to us. In fact, it’s impossible for us to know by our own lights: our limited minds cannot grasp the infinite wisdom of God’s intellect or the infinite goodness of God’s will. Only God himself fully understands.

In suffering and death, when we cry out to God in anguish, we should not be scandalized when God seems not to answer. He can’t give us the reason: our minds are too little to comprehend it. To grasp God’s will would mean seeing God face-to-face as he is in himself. Such a vision is beyond man’s capacity to see. This is not because God is absurd or unintelligible, but because he is too intelligible for us. The light of God’s face is too bright for us to see.

Knowing our human limitations, God’s answer is to give us supernatural sight: the bright obscurity of faith. This faith, joined with the confidence of hope and the friendship of God’s love, aids our eyes as a torch in the night. Its faint glow doesn’t illuminate the whole landscape. Rather, its flame fluttering upward toward heights yet obscure, it guides us along the narrow path to the heavenly source of its blaze. At the journey’s end, as a sunrise, we shall see God face-to-face, and every tear will be wiped away.

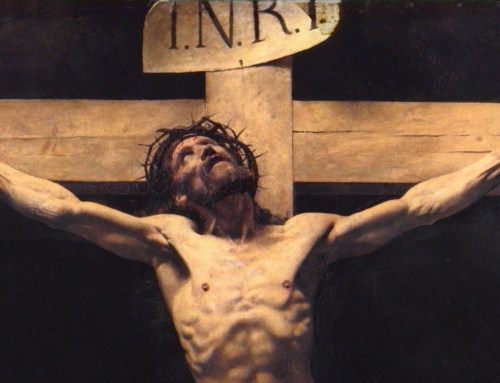

In the end, I told my friend that I don’t know why God let this happen. There’s so much I don’t understand. But I love Jesus. I worship the God who himself died on the cross. The cross of Christ is what I know, the cross is my answer, and in the cross I hope.

✠

Image: Gerard van Honthorst, Mocking of Christ