In 1162, something scandalous happened. The monks of the cathedral chapter of Canterbury, under pressure from King Henry II, elected the deacon Thomas Becket as Archbishop. By any rendering, this was a political imposition. Henry hoped that Becket would be a tool, one who would cooperate with royal aims and help subordinate the Church to the Crown. Since the late 500s, Canterbury had been the most important diocese in England. Its bishop led the English Church, and he presided over the major national ceremonies, like the coronation of the king. Typically, the bishop was a monk, sometimes from the cathedral’s monastery. The see had such notable monk-bishops as Saint Anselm, who, only a half-century earlier, had upended King Henry I’s attempted power-grab during the investiture controversy.

Thomas Becket was no monk. He was smart, but worldly. Earlier, Becket’s talents led him to become Henry’s chancellor, serving Henry in many unsavory affairs. He levied unprecedented taxes—six times higher than before—on the Church. Cleric though he was, Becket fought in Henry’s wars on the continent. He had a great love of falconry and elaborate hunts, practices austere men found rather frivolous. He brought two dozen outfits of fine silk and furs on a diplomatic mission to Paris, wearing each garment only once or twice. To top it all off, Becket’s Latin was mediocre. Such was the man the king forced upon Canterbury. Such was the man to shepherd the Church in England.

Despite everything, the Holy Spirit was working. He was working for the sake of the Church. He was working for the sake of the people of England. He was working for the sake of Thomas Becket. Upon ordination and consecration, Becket began to change.

After a few months as Bishop, Thomas Becket renounced the powerful role of chancellor. After a year, he abandoned his luxurious silk for a simple robe. He ceased hunting and falconry. Most importantly, he dedicated himself to study the Scriptures and hired the theologian Herbert of Bosham as his tutor. In this period, his writing dramatically changed; his letters became saturated with biblical quotes. God had enlightened Becket’s mind, and Becket was renewed.

Becket no longer fought for the king, but for God and the Church. He disputed with the king and the bishops who capitulated to the Crown. He refused to dispense Henry’s brother William from the law of consanguinity, preventing William from marrying his third-cousin for political advantage. He fought to recover lands that barons had stolen from the Church in previous generations, and he opposed Henry when he undermined ecclesiastical laws.

By God’s grace, Becket was a pawn no longer. Yet his conflicts with the king would lead to his earthly undoing. He went into exile and spent years in abbeys in France. Expecting danger, he returned to Canterbury. Four knights came to demand that he change his tune, but Becket refused, “In vain you threaten me. If all the swords in England were aimed at my head, your threats could not dislodge me from my observance of God’s justice and my obedience to the lord pope. Foot to foot you shall find me in the battle of the Lord” (Fitzstephen, The Life and Death of Thomas Becket). The knights fled for a few hours, but Becket did not flee. At Vespers that evening, the knights entered the cathedral and cut him down. Throughout it all, the martyr kept his composure; their swords did not dislodge him.

The Lord is not mocked. In every age, princes try to bend the Church to their will. At times, they seem to succeed. Yet in every age, the Holy Spirit moves hearts to protect the Church. By grace, he transformed St. Thomas Becket into a warrior for the Lord and a true shepherd of the Church. He still moves hearts today. Today’s commemoration of St. Thomas Becket reminds us that the Church will never fall, for the Holy Spirit is living and active. He transforms even worldly courtiers into saints.

✠

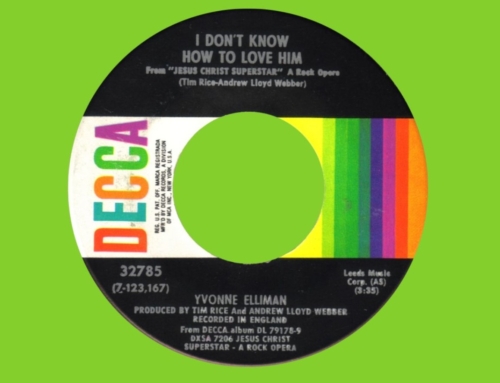

Image: Willem Vrelant, The Martyrdom of Saint Thomas Becket