I still remember the first time I encountered the writings of St. Augustine. I was taking a class called “Augustine and Aquinas” in college and had to read Augustine’s Confessions alongside Aquinas’s Compendium of Theology. The difference between the two was striking. Compare Aquinas and Augustine on man’s last end:

Our natural desire for knowledge cannot come to rest within us until we know the first cause, and that not in any way, but in its very essence. This first cause is God. Consequently, the ultimate end of an intellectual creature is the vision of God in His Essence. (Compendium, 104)

And now Augustine:

You stir man to take pleasure in praising you, because you have made us for yourself, and our heart is restless until it rests in you. (Confessions, I.1)

Which one do you think captivated a college student in search of God?

Now I admit that this is being a little unfair to St. Thomas; he was writing at a different time, to a different audience, with a different goal. In Pope Leo XIII’s encyclical Aeterni Patris Augustine is credited with “wresting the palm” from all the early Church Fathers. “Of a most powerful genius and thoroughly saturated with sacred and profane learning, with the loftiest faith and with equal knowledge, he combated most vigorously all the errors of his age.” But it is St. Thomas who is said to gather together and increase with his own additions all Scholastic teaching such that “he is rightly and deservedly esteemed the special bulwark and glory of the Catholic faith.” Indeed, “Reason, borne on the wings of Thomas to its human height, can scarcely rise higher, while faith could scarcely expect more or stronger aids from reason than those which she has already obtained through Thomas.” St. Thomas, not St. Augustine, is the theological master recommended by Pope Leo XIII to the entire Church.

And yet on the feast of St. Augustine it is appropriate to reflect on his ongoing significance and extremely wide reach. I do not think my initial reaction to St. Augustine was unique; his theological thought and style has captivated so many throughout history and continues to bear fruit in contemplation today.

The Holy Roman Emperor Charlemagne was so taken with St. Augustine’s City of God that he slept with it under his pillow. In Peter Lombard’s Sentences St. Augustine is quoted ten to fifteen times as often as any other Church Father, and in St. Thomas’s Summa Theologiae, it is St. Augustine who is the most referenced authority after the Bible. St. Thomas’s reverence for St. Augustine was so profound that even when he holds quite a different opinion he refuses to criticize him!

This Augustinian influence did not relax after the Middle Ages. It was an Augustinian friar (Martin Luther) who started the Reformation, and its greatest systematizer, John Calvin, famously proclaimed, Augustinus . . . totus noster est (“Augustine is totally ours”). The Reformed theologian B. B. Warfield declared, “It is Augustine who gave us the Reformation. For the Reformation, inwardly considered, was just the ultimate triumph of Augustine’s doctrine of grace over Augustine’s doctrine of the Church.” St. Augustine was on both sides of the debate!

Following the Reformation, St. Augustine still held preeminence in the minds of many influential thinkers. In the seventeenth century both René Descartes and Blaise Pascal saw him as the foundation of their own philosophical and theological projects—even though they were fundamentally at odds with one another (Pascal: “Descartes useless and uncertain”). In the nineteenth century Friedrich Nietzsche wrote The Genealogy of Morals, which can be best described as St. Augustine’s City of God argued backwards. The twentieth century saw St. Augustine’s Confessions as the model for both religious and secular autobiographies: American Trappist monk Thomas Merton’s The Seven Storey Mountain is contrasted with French philosopher Jacques Derrida’s Circumfessions. And let us not forget that it is St. Augustine who tops the citation list of ecclesiastical writers in the Catechism of the Catholic Church.

St. Augustine seems to have a timeless influence, an ability to speak across millennia and around the globe. He has been called the first medieval, the first modern, the first existentialist, the first autobiographer. It appears he has followed St. Paul’s dictum in being “all things to all men.” He has taught the world about God and its relationship to Him, historically and cosmologically. He has helped the Church understand the Trinity, the sacraments, and the doctrine of grace (he is, after all, the Doctor Gratiae). And if history is any indication, he will go on teaching the world, the Church, and each one of us about ourselves and our deepest desire for God.

In Book X of his Confessions St. Augustine says of God, “Late have I loved you, beauty so ancient and so new.” Perhaps we can say something similar about St. Augustine himself: “Always have we loved you, teacher so ancient and so new.”

✠

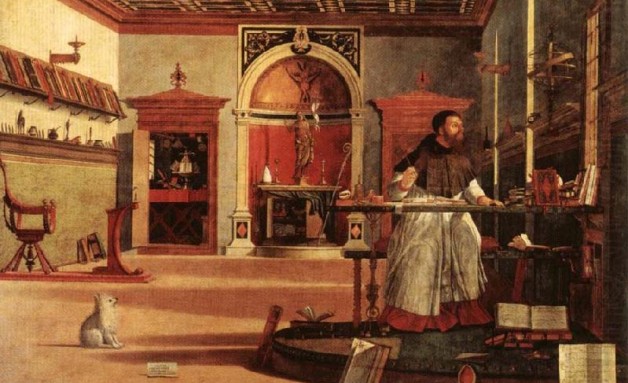

Image: Vittore Carpaccio, St. Augustine in His Study