Meditating on the Passion of Christ is like looking at a diamond which sparkles and shines from whichever way we examine it. On the cross, Jesus manifested the supreme possession of virtue in all its manifold brilliance. Recently, I was reading Aristotle’s description of the magnanimous man in his Nicomachean Ethics, and it struck me that the virtue of magnanimity applies supremely to Christ Crucified. To be magnanimous means to be great-souled. This virtue is described as the flowering of the man who lacks no virtue. Just as the body which has complete proportion is beautiful, so the soul that is complete in virtue is magnanimous. Christ shows himself to be magnanimous in many ways.

First, the great-souled person, as his name suggests, is concerned with great things. He never shirks opportunities to do great things, “but in exposing himself to danger acts ardently, so that he does not spare his own life, as if it were unfitting for him to prefer to live rather than gain great good by his death.” But in the face of the greatest danger, a painful and shameful death, Christ did not draw back from the greatest good: his Father’s glory, his own glorification, and the reconciliation of man with God. The magnanimous person doesn’t occupy himself with many things, nor with trivial things, nor with external things, but is completely taken up with the things that truly matter and which are interior, that is, with virtue.

Further, since the magnanimous person is concerned with the greatest deeds and actions, Aquinas concludes that “the proper matter of magnanimity is great honor, and that a magnanimous man tends to such things as are deserving of honor” (ST II-II, q. 129, a. 2). Through his virtuous action, the magnanimous person deserves the greatest honors. Now, Aristotle had no idea that man could receive honors from God in the afterlife, but he did point out that the greatest honors are from the greatest people. Christ sought the highest honors when he sought honor from his Father, and so teaches us to seek only this higher honor. On the eve of his Passion and Death, Jesus lifted up his eyes to heaven and said, “Father, the hour has come; glorify thy Son that thy Son may glorify thee” (John 17:1).

It is another mark of the magnanimous person to be more concerned with the truth than with the opinion of men. The magnanimous person “does not depart from what he ought to do according to virtue because of what men think.” He speaks openly, therefore, because to remain silent out of fear is foreign to the person with a soul replete in virtue. When abducted in the darkness of night and brought before the Sanhedrin, Jesus told his interrogators, “I have spoken openly to the world. . . . I have not spoken secretly” (John 18:20).

Another property of the magnanimous person is that he “neither complains by lamenting and grumbling about his lack of the necessities of life, nor asks that they be given to him.” This is because, in a true estimation, he holds these goods to be inferior and relatively unimportant. And Christ, lacking clothing, food, drink, and sleep, was “oppressed, and he was afflicted, yet he opened not his mouth; like a lamb that is led to the slaughter, and like a sheep that before its shearers is dumb, so he opened not his mouth” (Isa 53:7).

Finally, the magnanimous man “is not too mindful of the evils he has suffered. . . . Hence, Cicero said of Julius Caesar that he was in the habit of forgetting nothing but injuries.” Christ in agony and pain, tormented and insulted did not remember nor return insult, but rather defended his offenders: “Father forgive them; for they know not what they do” (Luke 23:34).

Aristotle tells us, and Aquinas agrees, that most people are pusillanimous—falling short of the virtue of magnanimity by defect. In other words, most people do not attempt to perform the great deeds that they are actually capable of doing, and this is not because of stupidity, but out of laziness. Through fear of pain, struggle, and of being ridiculed by others, most do not achieve the greatness that lies within their reach. If we turn to Christ and ask him for his magnanimity, he will grant us this crowning virtue and his own great strength to achieve it. “In your hand are power and might, and in your hand it is to make great and to give strength to all” (1 Chr 29:12).

✠

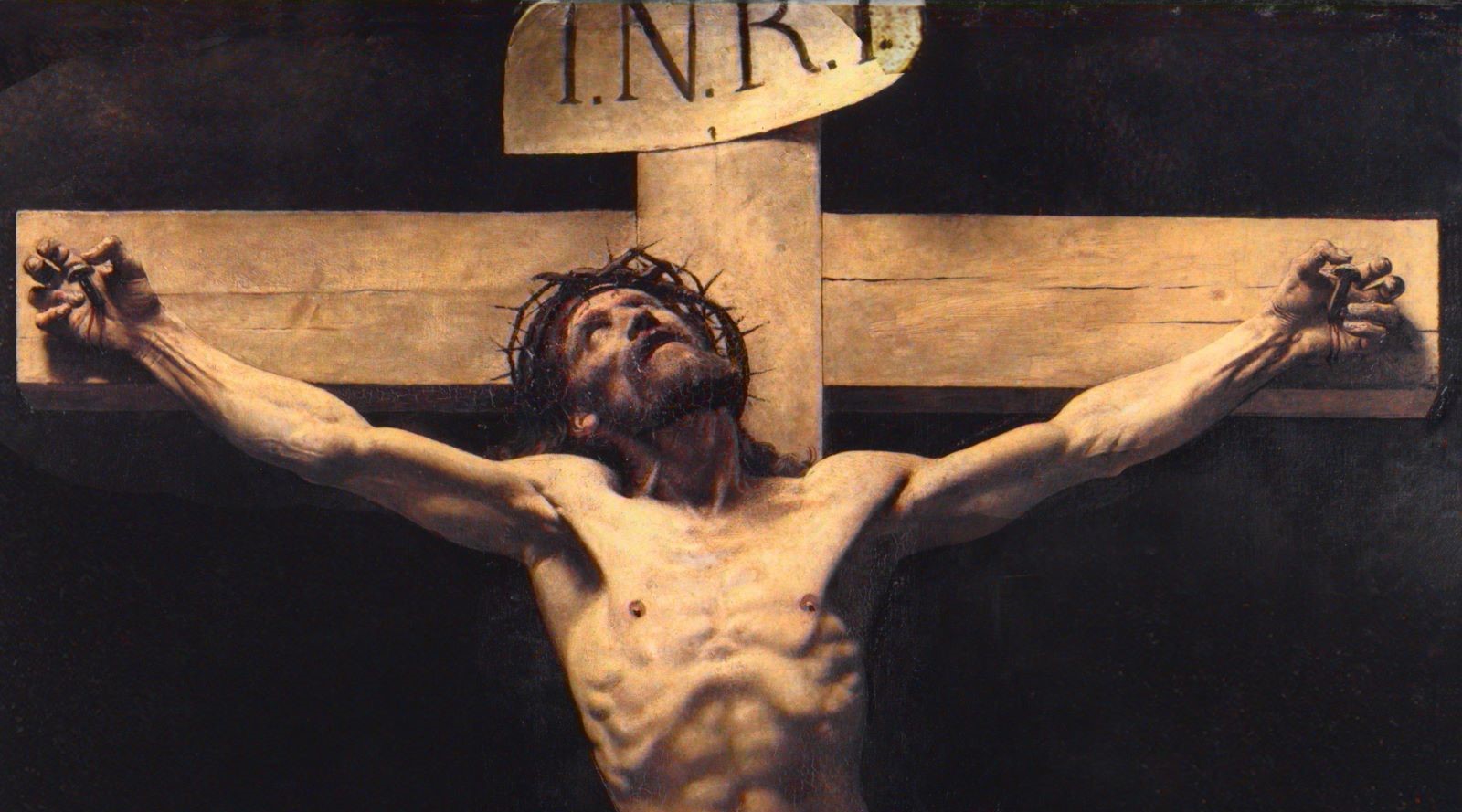

Image: Léon Bonnat, Christ on the Cross