The best moral formation often comes from music. It was my first year singing in our Dominican Schola and I was learning the intricate beauty of polyphony. A more seasoned brother leaned over and let me know that I’d really “internalized the tempo.” “Great!” I thought to myself, “I’m getting the hang of this.” My face must have betrayed self-confidence since he went on to explain that this wasn’t a good thing. His advice was simple, “You need a metronome.”

By “internalizing the tempo” I had stopped paying attention to the movement of the whole choir. I was internally consistent, singing the right notes, all in good time, but I had fallen off from the piece as a whole. Polyphony is an elaborate form of singing. It’s a conspiracy in which the singers must move and breathe together, in which the quality of each singer is not measured on the basis of his own sound, but on how each blends with others. Each singer must move and adapt to the sound of the whole, being drawn out of his own timing into a common tempo. The resulting glorious sound is only possible through the proper ordering of complementing pieces. If a part tries to dominate, the piece will fall apart. A choir’s perfection arises from this small community’s commitment to its common good.

In its mutual self-giving, polyphony appeals to our desire for communion. God made us in his image and thereby made us with a capacity for relationship (see Gen 1:26–27). By his own reckoning, it’s not good for us to be alone (see Gen 2:18). Man, a mystery to himself, is capable of communion and yet often chooses isolation. But like a choir, if we are to live with others in a genuine community it’s not enough for us to “internalize the tempo.” Our most beloved communities—the family, our country, our church—call for the same. Each asks us to sacrifice, to be pulled out of ourselves to work for something bigger. Our most basic and most life-giving communities, in John Paul II’s words our “natural societies” (Person and Act, 399), work in much the same way.

If we’re to have any hope of a genuine relationship we need a common good. And if we’re to have a common good we need a basis for that good—a shared sense of reality. Admittedly this is a low bar for human solidarity, but one which is increasingly disappearing. Instead, we settle for compatible senses of reality—like a choir opting for differing, but compatible tempos. The result is what you’d expect. If we view our communities as the mutual safeguarding of individuals, freely moving in and out of relationships we do not have community but proximity. Instead of the intricate layering of a polyphonic whole, it is a group of soloists singing near each other. If we want to live polyphonically, if we’re going to live in a true community, we need a common tempo, we need a moral metronome.

Since the fall man has sought to gaze inward. The result of our sweet solos is alienation. If our moral metronome is to draw our attention elsewhere and draw us out of ourselves, it must come from without. In our need for a moral metronome, John Paul points us past any human standard:

Only God, the Supreme Good, constitutes the unshakable foundation and essential condition of morality. . . . The Supreme Good and the moral good meet in truth: the truth of God, the Creator and Redeemer, and the truth of man, created and redeemed by him. Only upon this truth is it possible to construct a renewed society and to solve the complex and weighty problems affecting it. (Veritatis Splendor §99)

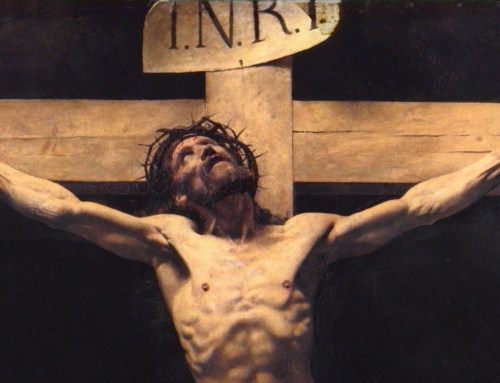

Saint Paul writes to the Colossians, “You yourselves were once alienated from Christ” (1:18). Alienated from God and his Image. But through the incarnation, Christ has revealed man to himself and provided an answer to his unrelenting longing (see Gaudium et Spes §21–22). Jesus Christ, the wisdom and power of God came in the flesh. He presented a new law of grace—not a set of abstract principles, but an example to be imitated. The Lord entered our world and told us to look elsewhere. He took on flesh and entered time and, like a well-trained director, he drew us into his own. Thomas Aquinas summarizes this mystery of intonation and imitation with Christ’s perfect symbol of love: “Whoever wishes to live perfectly need do nothing other than despise what Christ despised on the cross, and desire what Christ desired” (Commentary on the Creed, a. 4). We must be like Christ who not only forgave his persecutors but died for them. We must be crucified at his right and learn to be gazed upon in love by the Father. We must be pulled out of ourselves by that sign of contradiction and keep our eyes on the paradox of the cross. Like the flourishing sound of a polyphonic choir, living in freedom under grace is a gift demanding self-sacrifice and self-gift.

Jesus Christ came that we may live more polyphonically (cf. John 10:10). The alternative is a hellish cacophony of solos. It is an existential isolation, in which our commitment to self-consistency cuts us off from others, from our chance at true communion. To be our own measure (of musicality, of morality, of reality) is to be true to ourselves—and truly alone. But when Truth appeared in the flesh he shattered the darkness and isolation of sin. His beloved disciple tells us, “If we walk in the light as [Christ] is in the light, then we have fellowship with one another” (1 John 1:7). Jesus Christ, the very pattern of creation and its redemption, first draws us out of ourselves to himself. It is in him that we learn to live in true communion with others. A life of mere proximity is not worth living. But to live polyphonically, you’ll need a metronome.

✠

Image: Norman Rockwell, The Love Song