In the glories of spring, stepping away from the books more than usual to smell the flowers and soak in the sun and look at a bird . . . all these things seem fitting. And forgivable. Wisdom lies beyond the page as well. But spring is over, and summer has gone its way. It’s October, the flowers are dead, that bird has flown south, and kiss that sun goodbye!—earlier and earlier every day, in fact. The desk calls, and nature is no longer an excuse. You must read and read and read and focus and read more, and maybe write a little, and then read and—also, don’t forget to pray—and read, then maybe sleep, and read again and, oh yeah, you should probably read.

These are the thoughts that occupy my mind come fall. There is something about this time of year that funnels us indoors: back to school, back to the desk, the library, the books. For the eager student and the lover of learning, it’s not a death sentence, it’s a joy—but not without hesitation. Be it a syllabus, a personal plan of reading, or simply a desire to grow in knowledge this fall—formal student or not—one can easily grow weary of the task. Each of us only has so much time on our hands. How to keep it all in perspective?

“A vocation is not fulfilled by vague reading and a few scattered writings.” The French Dominican, A. G. Sertillanges, thought deeply about the academic life, and about the environment necessary for intellectual endeavors. In 1920, he wrote a little work called The Intellectual Life: Its Spirit, Conditions, Methods, which sought to encapsulate the essence of the intellectual vocation. He makes it clear throughout that the vocation to think deeply is not reserved just to degree-seekers and members of academe. The intellectual vocation can be taken up by anyone, that is, anyone who is willing to sacrifice pleasures, the free time he might have, and idle pursuits.

Sertillanges’ considerations in The Intellectual Life are comprehensive, for he covers everything from keeping a window open when you work, to the time of day conducive to study, to notecards, breathing habits, and newspapers. But one that sticks out to me come autumn, when the desk and the library call and a mountain of books needs reading, is Sertillanges’ treatment of the solitude necessary for study:

Retirement is the laboratory of the spirit; interior solitude and silence are its two wings. All great works were prepared in the desert, including the redemption of the world. The precursors, the followers, the master Himself, all obeyed or have to obey one and the same law. Prophets, apostles, preachers, martyrs, pioneers of knowledge, inspired artists in every art, ordinary men and the Man-God, all pay tribute to loneliness, to the life of silence, to the night. (The Intellectual Life, 48)

For any academic—family man and consecrated religious alike—solitude must be actively sought. And only then, when quiet of soul is found, can one throw all the powers of his mind and heart into his work.

Saint Jerome spoke frequently of solitude in relation to the desert. He exemplifies that that acquisition is not easily found. First, he dreams of finding solitude: “Oh! That I could behold the desert, lovelier to me than any city!” (Ep. 2). While his letters are primarily taken up with his requesting friends to send him books, commentaries, and the Scriptures, they frequently abound with news of how “his desert” is treating him. Once literally established in the deserts of Syria, study and contemplation did not come easily for Jerome: “Nebuchadnezzar has brought me in chains to Babylon, to the babel that is of a distracted mind” (Ep. 7). Jerome advertises for the desert passionately, yet he does not hide his failures and frustrations amid the supposed solitude: “O solitude whence come the stones of which, in the Apocalypse, the city of the great king is built! O wilderness, gladdened with God’s especial presence!”—and a few lines later—“Does the boundless solitude of the desert terrify you?” (Ep. 14).

Study is a hard business, but immensely rewarding. As the leaves change, will you face the mountain of books bravely? Seek out solitude, keep at it, and pray the Lord of Wisdom to make your endeavors fruitful. You will find that the wisdom of Solomon will be given you, herself coming from the desert:

Who is this coming up from the desert,

like columns of smoke

Perfumed with myrrh and frankincense,

with all kinds of exotic powders? (Song 3:6)

✠

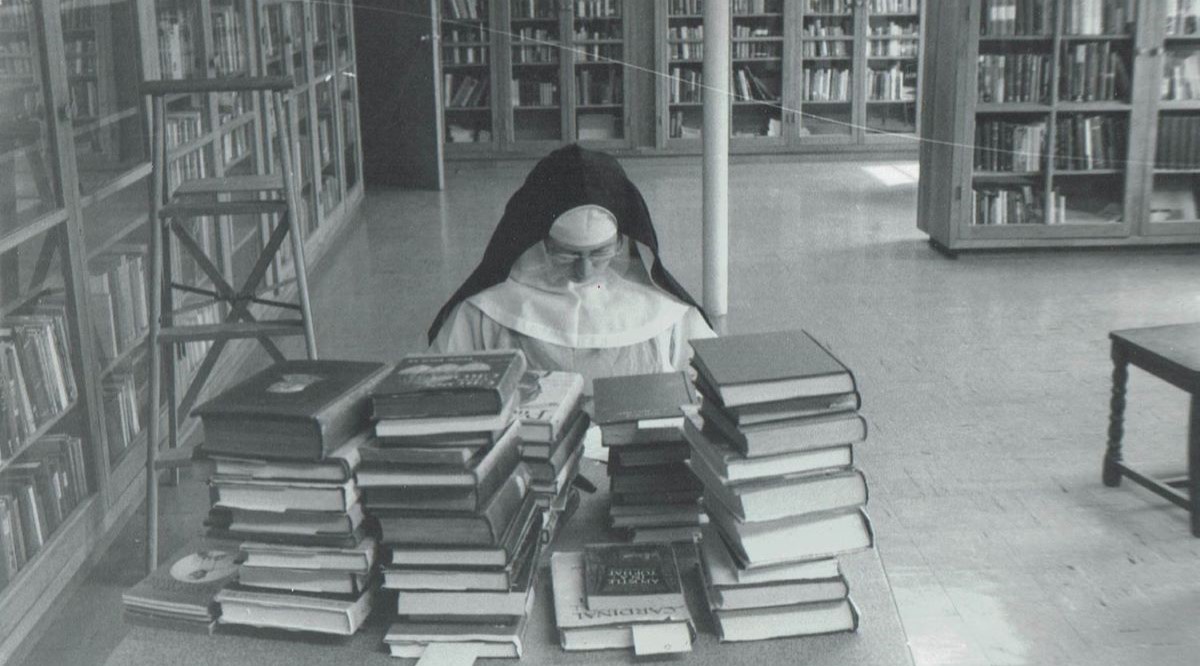

Photo from Our Lady of Grace Monastery, North Guilford, CT (used with permission)