Holy Innocents is a strange kind of feast. Amid all the great cheer and gentle warmth of Christmas, we commemorate a paranoid old king massacring innocent children. The day is a strange mix of deep, unutterable sorrow and light, playful joy. We have the weeping in Ramah, Rachel’s tears, the unconsolable maternal anguish (Matt 2:18). The sixteenth-century “Coventry Carol” (masterfully reworked recently by Philip Stopford) expresses hauntingly the last lullabies of these mothers:

Herod, the king,

In his raging,

Charged he hath this day

His men of might,

In his own sight,

All young children to slay.

Lully, lulla, lully lulla

By by lully lullay

Lully, lulla, thou little tiny child

By by, lully lullay

That woe is me,

Poor child for thee!

And ever morn and day,

For thy parting

Neither say nor sing

By by, lully lullay!

But the Church celebrates this heart-wrenching occasion as a Christmas feast full of gladness. These speechless children are held up as the first martyrs, unable to speak yet giving eloquent witness to Christ, dying for someone they didn’t yet have the mental capacity to know or believe in. What can turn the bitter cruelty of a petty tyrant into a yearly day of rejoicing?

Only the coming of a new kind of king. The paradoxes of the Feast of the Holy Innocents only make sense when Christ has upended the meaning of kingship. The fifth-century St. Quodvultdeus commented on this feast:

The children die for Christ, though they do not know it. The parents mourn for the death of martyrs. The child makes of those as yet unable to speak fit witnesses to himself. See the kind of kingdom that is his, coming as he did in order to be this kind of king. See how the deliverer is already working deliverance, the Savior already working salvation.

The Savior is scarcely born and he is already working salvation, planting the first seeds of the Church. An early Church Father famously remarked that the “blood of the martyrs is the seed of the Church.” He meant that the witness of the martyrs draws many to the Church, but the quote fits here too. The blood of the Holy Innocents are the first seeds of the growing Church.

These first seeds become the first flowers of the Church. And, indeed, the tradition often uses floral imagery to describe these little martyrs. The early poet Prudentius opened one hymn:

All hail! You infant martyr flow’rs,

Cut off in life’s first dawning hours;

Like rosebuds, snapped in dreadful strife,

When Herod sought our Savior’s life.

Saint Augustine and Saint Caesarius of Arles similarly describe the Holy Innocents as flowers, but use winter imagery to depict Herod’s cold cruelty. The children are “the first buds of the Church killed by the frost of persecution” (St. Augustine), “the blossoms of martyrdom,” which “a kind of frost of persecution along with cold unbelief consumed” (St. Caesarius).

The picture of winter flowers amid the frost is an apt one, imitating imagery of Christ’s birth. Jesus is a rose blooming that “came, a flower bright, / Amid the cold of winter / When half spent was the night.” Like the unexpected warmth of a rose amid the cold of winter, Christ’s birth was something new and unlooked for amid the winter-world of sin.

The surprising flowering of the Church we commemorate today displays the gratuity of God’s grace. Christ’s whole life overflows with a salvific generosity. Even at his birth, Jesus is at work saving the most defenseless, the most unable to help themselves, the most unjustly attacked. Although deprived of a long earthly life, our Lord welcomes them into the mature and eternal life of heaven. He joins their suffering to himself, allowing them to share already the fruit of his suffering. That is the kind of king he is.

In place of the paranoia of Herod’s kingdom, threatened by newborn infants, Christ opens his kingdom first to the least, making his first witnesses tiny children. That is the kingdom Christ calls us to.

✠

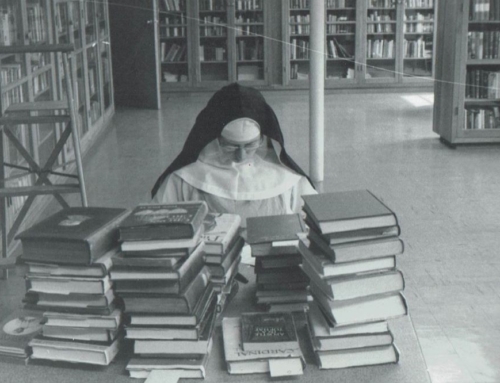

Image: Sano di Pietro, The Massacre of the Innocents