Recently I had the opportunity to speak with a class of third graders about Lent. Focusing on Jesus’ forty-day fast in the desert, I compared it to the Israelites’ forty years in the wilderness and to the “forty days and forty nights” of the Flood. My time with the class was brief, but toward the end I was able to take two questions. The first was, “Why does God allow people to do bad things?” and the second, “If Jesus was God, how come He had to come down to earth and die on the Cross?” Out of the mouths of babes … come tough questions. It didn’t hit me until I had left the classroom that these two particular questions are profoundly connected.

The first question involves the mystery of free will. God creates us out of love, and He wants us to love Him in return. We know from our own experience, however, that love cannot be forced. Even if the external signs of love are present, it’s not really love unless it comes from within, from the mind and heart, from the whole of one’s being. If God forced us to love him, our “love” would not be free and, therefore, wouldn’t be love at all. In fact, the very idea of forced love is a contradiction in terms, a non-idea, like a square circle or a round triangle. In order to love, we must be free, and, for those of us who do not yet enjoy the Beatific Vision, being free entails the possibility of choosing not to love, of sinning, of doing “bad things.”

This helps us to answer the second question, “If Jesus was God, why did He have to come down to earth and die on the Cross?” The simple answer is, He didn’t have to. He did it freely, out of love, and in so doing he both showed us the depth of his love and set us an example. After all, the greatest sign of love is suffering for another, sacrificing oneself for another: “No one has greater love than this, to lay down one’s life for one’s friends (John 15:13). Indeed, it is not suffering as suffering that has meaning, but suffering for the sake of. Jesus’ suffering was for our sake, and the great sign of this is that, although He was free to turn down suffering, to escape, to save us in some other way, instead He embraced the Cross and suffered death.

Another way of putting this is to say that, although Christ’s death on the Cross was not, strictly speaking, necessary, it was eminently fitting. And it was fitting in more ways than one. For example, just as, in the beginning, a tree was the occasion of our death through the disobedience of Adam, so now another tree—the Cross—is the occasion of new life through the obedience of Christ. Jesus, the new Adam, true God and true man, makes all things new. No longer are we bound by sin, to labor through this life, only to reach its end in darkness and death. Now we have new life in Christ, if only we choose to live in Him, with Him, and through Him.

It is true that we do not get to choose the cross that is ours to bear in this life, but whether or not we accept our cross for love of Jesus Christ and for love of the people he has given us, is our choice. We can embrace it or reject it; we can resent it or be healed by it. If this choice makes us sad or afraid, let us take consolation in the fact that a God who has himself suffered so much for us will not abandon us in our suffering. He will be with us and help us, even when we do not perceive it: “Can a mother forget her infant, be without tenderness for the child of her womb? Even should she forget, I will never forget you” (Isaiah 49:15).

✠

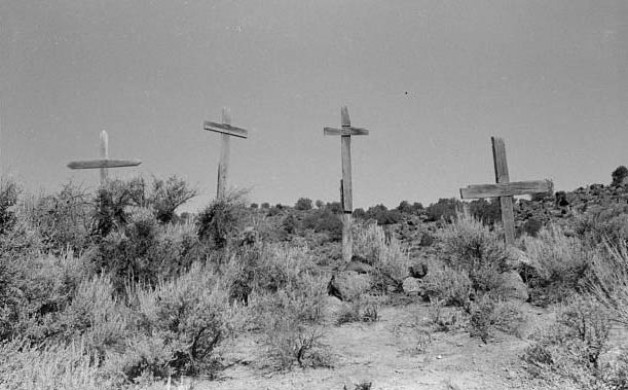

Image: Crosses in the Desert, near Embudo, New Mexico