Let the brothers reflect on and make known the teachings and achievements (gesta doctrinamque) of those in the family of St. Dominic who have gone before them, while not forgetting to pray for them. (Book of Constitutions and Ordinations, 160)

Pax in Lumine

José María Cabrera, O.P.

Translator’s Introduction

This is the message we have heard from him and proclaim to you, that God is light. — 1 John 1:5

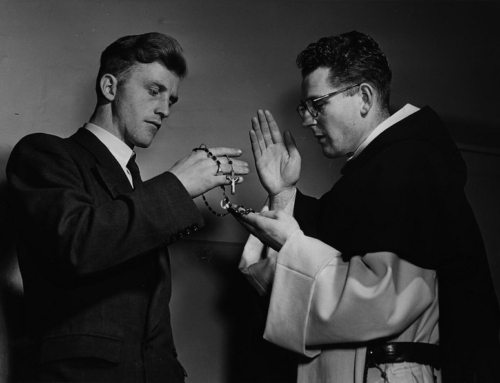

Fray Guillermo Butler contemplated the divine light and, painting, handed on the fruits of his contemplation. Fray Guillermo was born John Butler in Italy in 1879 to an Irish father and an Italian mother. Early on, his family moved to Argentina. As a child, he attended Colegio Lacordaire of Buenos Aires, a school run by French Dominican friars. He soon developed a talent for painting and an interest in the Order of Preachers. He entered the Order in 1894, in the priory of Santo Domingo in Córdoba, Argentina. He professed simple vows in 1900 and was ordained to the priesthood in 1907.

Though his provincial sent fray Guillermo to Rome to study canon law, the Master of the Order, Bl. Hyacinthe-Marie Cormier, diverted fray Guillermo to Florence to develop his talent for painting. There he drank deeply of the contemplative spirit of the earlier friar painter, Fra Angelico. He also studied for a few years in France, where he found a love for stained glass, from which he produced windows that still adorn some Argentine Dominican churches.

In 1915 he returned to Argentina, and for four decades he worked at adorning churches and Dominican priories. He painted the Argentine countryside, Dominican cloisters, and scenes from the lives of Jesus and Mary. In 1939 he founded the Academia Beato Angelico in Buenos Aires, an institute to teach and promote sacred art. His art students loved him, and young friars in the studium, the Dominican house of formation, sought him out as a wise and gentle confessor. Fray Guillermo died in 1961, but his works continue to witness to the God who is light.

The following meditation was originally written for a catalogue of an exhibition on Butler held by the art institute, Colección Alvear de Zurbarán of Buenos Aires in 2015. The author is fray José María Cabrera, a Dominican friar of the Province of Saint Augustine (Argentina). Fray José María entered the Order in 1980 and was ordained a priest in 1987. He now serves as Master of Students in Buenos Aires. I am grateful to him and to Dr. Ignacio Gutierrez Zaldívar, director of Zurbarán, for promoting Butler’s work and for permitting me to translate this meditation and to use some of Butler’s images in this issue of Dominicana.

*****

It has been more than fifty years since fray Guillermo Butler, the friar painter, passed from this world, and the Colección Alvear de Zurbarán offers us a selection of his work as an homage to him.

The organizers have asked us his brothers, the Dominican friars of the Order of Preachers, for our humble reflection about the works in this exhibition and about the thread running through all of them, uniting them. This attempts a synthesis of the artist’s immense corpus and of his message: the re-creation of the world through beauty.

We can group the works of fray Guillermo Butler put forward in this exhibit in three great paradigms that are linked and mutually contained: the landscape, the cloister, and the sacred image.

The Landscape

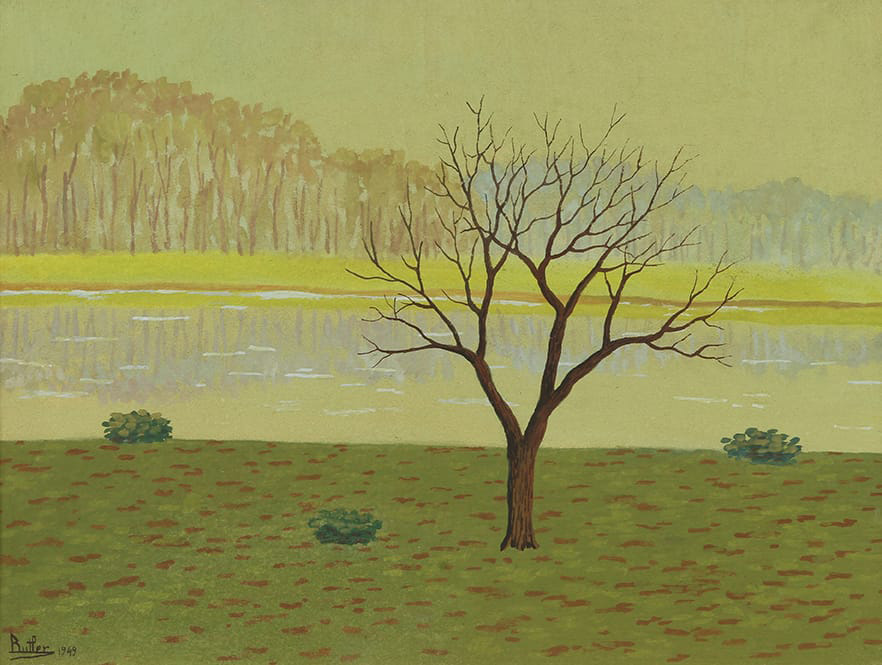

The landscapes proposed are a pilgrimage through nature’s four seasons—a peaceful epiphany of light. It is autumn—autumnal light—that prevails in this exhibit. The Light streams from the gold and ochre tones of the leaves, the rocks, the soil. How captivating—like the mist—are the sunset reds!

Autumn’s Light is a gentle light, which beckons unto nostalgia, to the desire of returning to an origin we lost. The peaceful light of Butler’s autumns makes us desire a permanent Home, not subject to falling hopes and dreams. The tempered light of autumn is a profound invitation to interiority, to leave behind appearances and superficiality. It calls us to seek the depths of reality. Autumnal colors beget poetry, and in turn, poetry contemplates the whisperings of undying Beauty, there in that place where one who does not have roots in his heart can only see the fall of leaves and fruits.

God is the first poet. . . . Every poet treads over the fallen leaves, over the golden paths of existence, sometimes broken and wounded, and through that treading makes fertilizer of hope and germination. It would seem that fray Guillermo has walked these sunsets in silent dialogue with God the poet.

A new creation awaits and will come forth after the dead leaves. Butler’s autumn light does not harm the pupils . . . His are not bewitching colors that overwhelm the senses. Rather, they invite us to prayer. They make us close the eyes of the heart to perceive the mysterious poet, that God-poet walking and dreaming within us. God is a poet and in speaking us—in his Word of Love, his Son—in his personal Light who is the Word, he calls us to existence and life even in the midst of the saddest falls of our autumns.

The twilight of Butler’s autumns gives birth within our hearts, drowsed by appearances, to the return, to conversion, to the desire for the loving Poet, the loving God. Those pristine spaces of his autumnal landscapes, the calm and meek lake waters, soothe the heart, feverish in its passions and in the hyperactivity of the unreal, of the void.

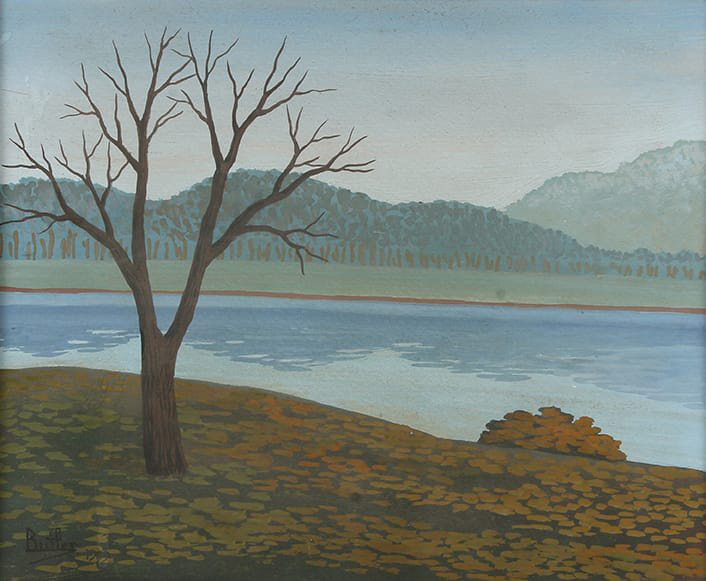

The blue shadows of sunset, decked with the dark rose of the parting sun, tell us of the peace of a God who calls us, who desires to create a “landscape” of pristine skies, of meek waters, of leaden blue, in the soul—in our soul. A soul that he has created through love, as his most beloved autumn poem . . . Don’t we find in these works the silent Love of the poet-God? After the autumnal twilight by which we recognize the steps of the poet-God, we cannot but linger on the winter landscapes: “Invierno en el Lago,” “Río Paraná,” “Solitario.”

By the wintry lakes, Lenten hues surprise us: crystalline purples reflected in the mirrored lake; intense, dark greens in the depths of the wooded forest; the soil with darkened grass; the naked tree that extends its hands in thirsty supplication; the closed and leaden sky—above all in “Invierno en el Lago” and in “Río Paraná.” The artist—who writes his spiritual theology in colors—talks to us of conversion, of life going inwards, of the vital sap no longer exteriorized in diversified expressions that break the unity of one’s heart, of the integrity of our own person in God.

Winter is Lent, the dark night of faith, the soul’s crucible. It is the hour for one to re-concentrate, to find again the axis of life, the root of life in God. That God who at the beginning of our turn toward him seems like a closed and leaden sky. But as the sap of life gathers itself within—like the trees in wintertime—he begins to manifest himself in light sky-blue, in far-off and near coasts—as we contemplate in “Solitario”—with a pristine green, nascent, sprouting. It is the greenery of Grace which makes us return to the garden of the Poet, of the God-Love, who created us for himself.

The pictorial space begins a crescendo of light from the purple of penance to the nascent green coasts of a new creation, far but seemingly near and accessible. Spring draws near. Easter is already sprouting. The naked tree, whose sap hid in the depths of its life, with its arms outstretched in mute supplication, tells us about the Cross. The naked Cross in the night of faith that every friend of the Crucified must experience. Fray Guillermo was a true friend of the crucified.

The despoiled tree is a call, a trusting cry to the sky that is clearing up, to the sky that reflects once more the blue of Divine Life, open and given to the human heart.

From the closed sky of “My God, my God, why have you abandoned me?” to the peaceful and clear one of “Father, into your hands I commend my spirit.” Winter . . . The poet-God is no longer found on the paths dreaming and composing; he is found hidden in a tree, in the wood of the Cross, suffering for us and clearing the sky for us: Will we be there with him?

After the stages of manifesting nostalgia for God, for that God who wants to write his best poetry singing to us from his love, passing through the nakedness and despoilment of what divides and estranges us; after living next to the tree of the Cross, next to Love Crucified, in the night of supplication and pardon, in the trusting abandon under a sky still closed and leaden; after these “seasons” of the soul, one arrives at the exultant Easter of spring which bears fruit in summer. It is the season of betrothals and weddings—its colors are the colors of love. The color of a soul ecstatic before the beauty of the Beloved God. It is the garden of the Song of Songs. They are the golden Sierras with a wide, open, ascending path that gets lost in the heights—in the spousal union of the soul with God. And on the mountain, a high mountain covered by a hidden splendor, pregnant with light and divine Presence, there is an invitation to ascend to seal a covenant, to speak face to face with the God-friend.

The warm color of the Resurrection morn; the reflection of the Sun, born among tears of abandonment, now transformed into tears of love for the now never-ending Presence of the Lord. This is the experience born from contemplating his work “Luz Dorada” . . . the light of the Risen Lord stamped upon us.

The Cloister

After tracking the footprints of God the poet in his creatures, by the eyes’ listening that knows how to listen for the call of God, the song of God, through their colors, the colors of their times, their shapes, of their dawns and sunsets, we cannot omit stopping before the landscape that is the cloister.

In this exhibit we encounter various cloisters. The monastic cloister is born as an imperious need to consecrate a space of nature, of creation, to relive in it the primal experience of paradise. The cloister must be that paradise where the Lord descends each evening. God in Jesus lowers himself, inclines himself toward us to talk and to treat his creatures as friends.

The cloister is the restoration of paradise: emerald greenery of filial Grace in consecrated hearts, hearts whose only desire is to live the life of the Son of God, his surrender to the Father. The cloister recreates the four rivers of paradise: they are the channels of the Water of eternal life, the Spirit of Beauty which from filial hearts bubbles up in fountain-song, in the chirping of birds, in the solemn melody of bells, in the spirit of the psalmody. We return in poetry, in psalms and hymns, to the poet-God who has spoken to us. Yes, the poet-God has spoken to us—loving us—first.

Religious life seeks to make of the cloister a paradise that God may descend and recreate with the monk, to talk to him, and to make him a reflection of his own light and beauty. We see this experience of Peace in Light in the cloisters shown in this exhibit. A light that enters through three great arches imaging the Three Persons of the Luminous Trinity; a light that pacifies the soul and turns it into a sower of peace.

Pax in lumine . . . we could say that of Butler’s cloisters. This light teaches everything to the monk, to the preacher, to the seeker of God. Light is merciful, light does not condemn; it enlightens, it transforms . . . The whole Christian life consists in transforming light into love.

The Sacred Image

Together with these cascades of light in God’s new garden, fray Guillermo does not neglect to paint Her who is the enclosed Garden, the New Paradise, the Garden of the fullness of Grace: Mary. It is she who has given us the most beautiful of the sons of men: Jesus Christ. She, giving her Fiat, united in the Incarnation our fallen nature to the Divine Beauty.

That is what we can contemplate in the third motif, the third paradigm of this exhibit: the sacred image. Mary, the Immaculate Virgin, the Mother of God who embraces the Child . . . the Mother of men who lives her dormition, her passing to God, enraptured by love, is the compendium of all natural beauties.

Saint Bernard sang of Mary as the “primal form” of creatures. God made the universe for Mary, because she is the Universe, beautiful and pure, for his Son, his Word. Mary, in her immaculate being, in her Fiat full of faith and love, is the Mother of the recreation of all things. Mary’s being is a spring without twilight. Mary is also the cloister of Light; her womb is the space of beauty where we are conceived in the form of the Son, the very Beauty of God.

Mary is the cloister, her Immaculate Heart is the cloister: there we allow ourselves to be begotten by the Word and are born as sons of the Father. In the Marian cloister we are given Jesus Christ: the joyous Light of the Father, the eternal Beauty, the spotless Mirror of the Father. The Light before which all colors fade. The Light under which we can glimpse every truth, every other small spark of truthful light and—for being so beautiful—even in the twilight of this world. Landscape, cloister, and sacred image are fused in Jesus Christ into a single living and personal reality. They spring from his unique Light as the Word of the Father, the seal of his Beauty.

Translated by Josemaría Guzmán-Domínguez, O.P.

✠

Download a PDF of this article here