Editor’s note: This is the second post in our newest series, Beholding True Beauty, which consists of prayerful reflections on works of sacred art. The series will run on Tuesdays and Thursdays throughout the month of October. Read the whole series here.

Indeed, an essential function of genuine beauty, as emphasized by Plato, is that it gives man a healthy “shock”, it draws him out of himself, wrenches him away from resignation and from being content with the humdrum—it even makes him suffer, piercing him like a dart, but in so doing it “reawakens” him, opening afresh the eyes of his heart and mind, giving him wings, carrying him aloft.

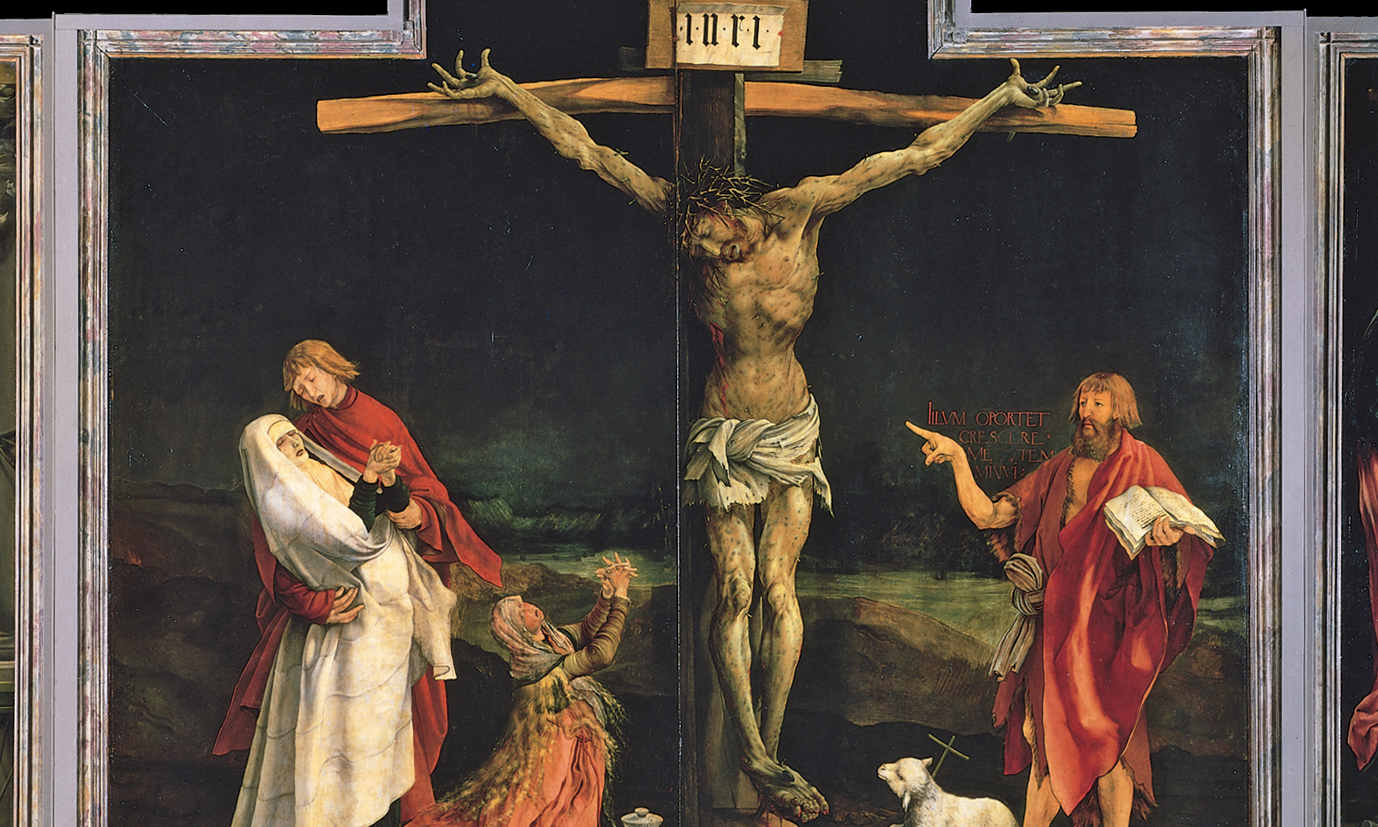

To be convinced that the famous altarpiece painting of Isenheim belongs to the category of “genuine beauty,” as described by Pope Emeritus Benedict XVI, one need only look at Matthias Grünewald’s masterpiece.

Indeed, Pope Benedict’s word “shock” seems appropriate here. What could be more shocking than a realistic portrayal of suffering and death, especially Our Lord’s. To the modern Christian, for whom images of the crucifixion are so commonplace and familiar, the Isenheim Christ can initially repulse him rather than draw him in. The depiction here is not a kitsch ornament or piece of decoration, nor is it an unintelligible and sterile abstraction. It is a bold attempt at outlining, coloring, and rendering an image of the fulfillment of the Messiah’s divine mission in all of its historical concreteness. It is the most beautiful event in history—the salvation of mankind through Our Lord’s death on a cross.

A close inspection of Grünewald’s crucifixion scene, however, shows more than mere historical realism. One is surprised to see, for example, John the Baptist at Calvary alongside John and the two Marys. His red garments with the white of his book and the lamb at his feet mirror and compliment the red of the Beloved Disciple as he supports the Mother of God draped in white. John’s words offer a scriptural reflection for the viewer:

Illum oportet crescere me autem minui.

He must increase, but I must decrease (Jn 3:30).

Grünewald vividly depicts this in a literal way. Christ’s body is disproportionately larger than the bodies of all other figures at the foot of the cross. The weight of his body seems to bend the slender cross-beam of the twisted tree on which he hangs. The eyes of the viewer also gravitate more to John’s pointing figure—unnaturally bent and elongated—rather than John himself. It is John’s message which is important. Christ must increase, I must decrease. My life is not about me. St. Paul also articulates the principle of Christ’s primacy in the life of the believer:

I have been crucified with Christ; it is no longer I who live, but Christ who lives in me; and the life I now live in the flesh I live by faith in the Son of God, who loved me and gave himself for me (Gal 2:20).

Noting Paul’s language of participation—I have been crucified with Christ—we should consider the context of the Isenheim Altarpiece. Grünewald painted the masterpiece in the early 16th century for a hospital monastery whose monks treated victims of what was then known as “St. Anthony’s Fire.” This disease, known today as ergotism, would cause its victim’s skin to peel and become gangrenous. Convulsive symptoms would curl and contort a victim’s hands and feet. Looking at the corpus of Grünewald’s painting, one observes pale, splinter-ridden skin along with hands and feet twisted in a kind of rigor mortis. Would this not have drawn the minds of both victim and caregiver to the correspondence of their suffering with Our Lord’s? To the reality that suffering is not meaningless, but salvific and even constitutive of the Christian life?

Then Jesus told his disciples, “If anyone would come after me, let him deny himself and take up his cross and follow me. For whoever would save his life will lose it, but whoever loses his life for my sake will find it (Matt 16:24-25).

Now I rejoice in my sufferings for your sake, and in my flesh I complete what is lacking in Christ’s afflictions for the sake of his body, that is, the church (Col 1:24).

The Isenheim altarpiece certainly shocks. But its beauty also draws us out of ourselves and opens our minds and hearts to the great mystery of the Cross and the Good News of which it is a part.

✠

Image: Matthias Grünewald, The Crucifixion in the The Isenheim Altarpiece