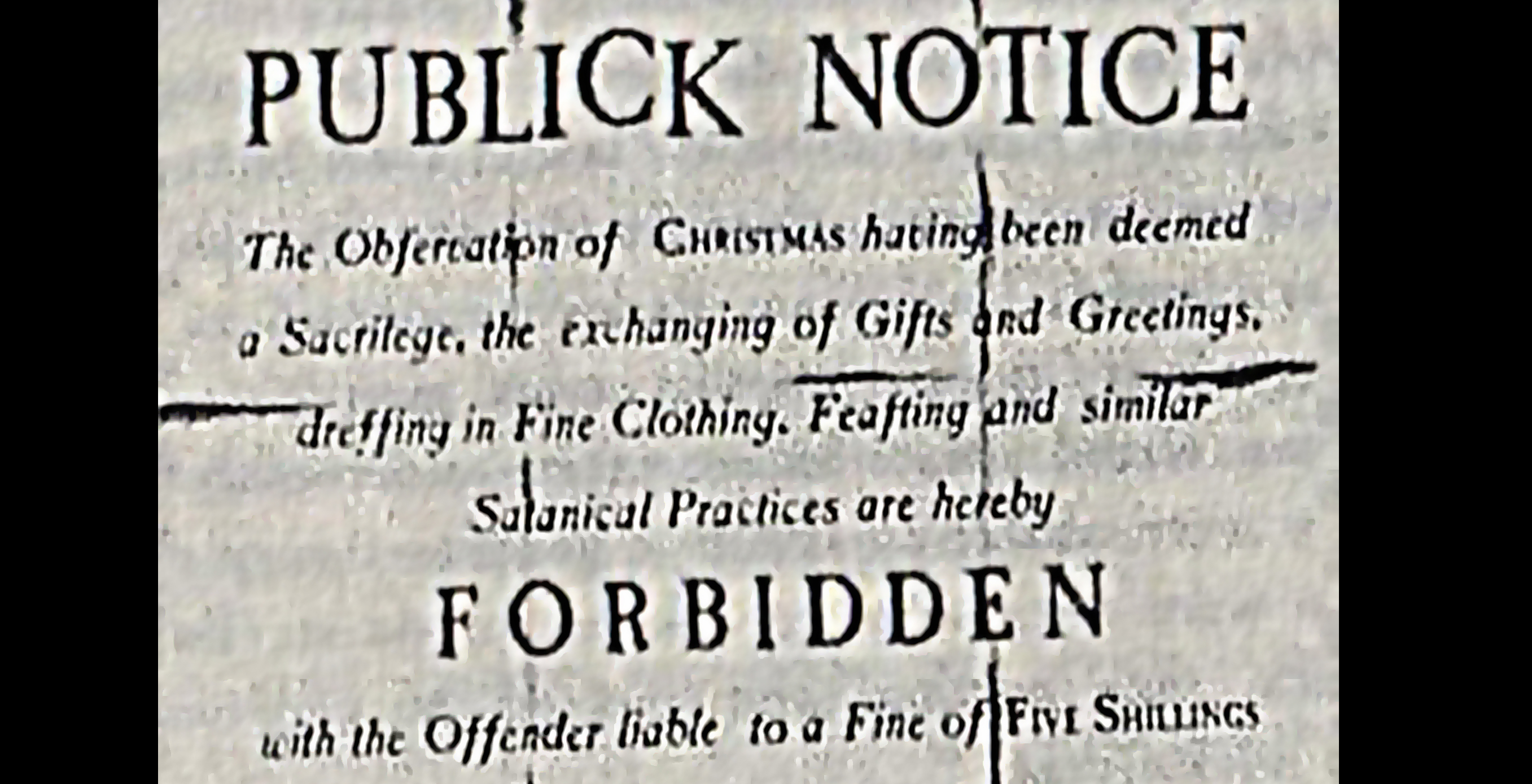

Walking through Boston on December 25, 1659, you would see no Christmas trees and hear no caroling. There was no exchanging of gifts and greetings, no dressing in holiday garb, and no celebratory feasts. There was only another day of work.

It was Christians, the Puritans, who outlawed what they deemed “satanic practices,” just as they had done in England a decade earlier; in an attempt to stamp out the holiday, offenders were fined five shillings. It turns out that the oldest New England Christmas tradition is the “War on Christmas.”

The Puritans had two objections to the Christmas celebrations. First of all, they were scandalized by the festivities of the day, and in their eyes the feasts and carols were nothing more than gluttony and inebriated carousing, a veritable cornucopia of sins of the flesh. In the words of one preacher: “the feast of Christ’s nativity is spent in reveling, dicing, carding, masking, and in all licentious liberty. . .by mad mirth, by long eating, by hard drinking, by lewd gaming, by rude reveling!” Perhaps he overreacted. You might even say he was a bit puritanical! Imagine their reaction to St. Francis’ exhortation to his brothers: “It is my wish that even the walls should eat meat on such a day, and if they cannot, they should be smeared with meat on the outside!”

Less polemically, and working out of their theological perspective, Puritans rejected the very notion of a Holy Day. It was reportedly their maxim that “they for whom all days are holy can have no holiday.” They embraced instead a radical and intentionally ahistorical simplicity, which denied the Church’s sanctification of people and culture through the means of everyday occasions—like feasts and holidays—that have been elevated in the life of the Catholic Church to signify divine mysteries.

Christ taught a sacramental worldview, as the Church would later describe it, in which the ordinary physical objects of human life can signify and convey God’s work among us. Through Christ’s power, mud and spittle restores vision, the bread of wheat becomes Christ’s flesh, ordinary water washes away sins. This action overflows beyond the seven sacraments, even extending past the many sacramentals, to make the most seemingly mundane aspects of life signify and participate in the sanctification of the world. The calendar signifies the ongoing work of God throughout history, as certain days are made holy fasts or feasts. Those feasts present a preview of the great wedding feast of the Lamb. Gifts are given to manifest our love for one another in a reflection of the Lord’s loving gifts. Even dressing in fine holiday clothing shows our desire to dress our souls in a manner worthy of the Lord’s feast (Matt. 22:1-14). As such actions can signify something holy, the Holy Spirit can be present among us and can vivify our lives with what is holy.

Most Protestant denominations reject, in different ways and to different extents, this sacramental worldview. They downplay the truth that Christ has used or can use the ordinary elements of life as means to bestow grace; this is a great poverty in their doctrines. The Puritans were extreme among denominations in the degree and consistency in which they rejected the sacramental worldview. They also possessed an astute and accurate sense that when Christians observe Christmas celebrations, festivities both explicitly and implicitly religious, they powerfully participate in the sacramental sanctification of the world.

This year, unlike in 1659, Christmas cheer is entirely legal. Enjoy the holiday, exchange gifts and greetings, dress in fine clothing, and feast! Let all your celebrations, by the power of the Christ-Child living among us, be like sacramental signs and means of Christ’s grace, who is making the world to be good and holy.

✠

Image: Public notice from 1659 in Boston regarding the banning of the celebrations of Christmas.