It’s that time of year again: political season. With primaries and national campaigns starting sooner than ever, we are already being inundated with political talk, spin, thought, and debate. The issues are being bandied about with the usual vitriol and condemnation: unemployment, the economy, national defense, immigration, education, healthcare, etc. Republicans or Democrats, liberals or conservatives, progressives or traditionalists; the answers lie somewhere in these dichotomies. But in the midst of this season it is important to recognize that one central issue is not being mentioned; in fact most of us have probably not even thought it a political issue: prayer.

The great Jesuit Jean Cardinal Danielou reminds us why we should consider prayer in a short book called Prayer as a Political Problem:

“The reader might be surprised by the title given to this chapter and this book. Public policy and prayer are two realities not usually brought together in this way. I have chosen the heading deliberately, because it seems to me essential to make it clear—perhaps somewhat provocatively—that there can be no radical division between civilization and what belongs to the interior being of man; that there must be a dialogue between prayer and the pursuit and realization of public policy; that both the one and the other are necessary and in a sense complementary.”

Cardinal Danielou was writing in the sixties in France, where the development of a technological socialism was threatening to crowd religion out of society. The political realm was (and is) seen as separate from the personal religious life of men and women. For him this is a crucial error:”A city which does not possess churches as well as factories is not fit for men. It is inhuman. The task of politics is to assure to men a city in which it will be possible for them to fulfill themselves completely, to have a full material, fraternal, and spiritual life.” Danielou argues that modern society is moving in a direction which will exclude the life of prayer for the majority of people; the spiritually “strong” will always find a way to pray, but the average person needs help.

“We ought never to forget that the Church is the Church of Everyman. The salvation which Jesus Christ comes to offer, the life which he comes to give, are salvation and life offered to the poor—to all—and what is offered to all must be within the reach of all. Yet today, for most men, given the circumstances in which they find themselves, the realization of a life of prayer is practically impossible… A world which had built up its culture without reference to God, a humanism from which adoration was completely absent, would make the maintenance of a positive religious point of view impossible for the great majority of men.”

Now you might think he is calling for some reactionary model of politics and prayer, a neo-Constantinianism, especially in the context of a post written by a man wearing a medieval habit. This would be a nostalgic impossibility. There is no hope for a “Benedictine escapism” from the world; rather, in an Augustinian register he declares:

“I have no liking for Christians who will not touch the facts of human existence for fear of soiling their hands… I love that Church which plunges into the thickets of human history and is not afraid of compromising itself by getting mixed up with men’s affairs, with their political conflicts and their cultural disputes.”

Cardinal Daneliou is calling for all Christians, especially Catholics, to rethink how prayer can become a constituent element of political life in a modern democratic society—for the sake of all those poor who do not know how to pray on their own.

What does this mean for all the dichotomies mentioned in the first paragraph? Which party, persuasion, or attitude will support political prayer? The answer is probably none of them, right now; but finding the right answer always begins with asking the right question. Maybe asking the question of political prayer is enough for now. As John Milbank says: “Once, there was no ‘secular.'” Perhaps reflection, action, and above all prayer can lead us to something like this again. A time, following Cardinal Danielou, when the Church can again “work at the task of making civilization such that the Christian way of life shall be open to the poor.”

✠

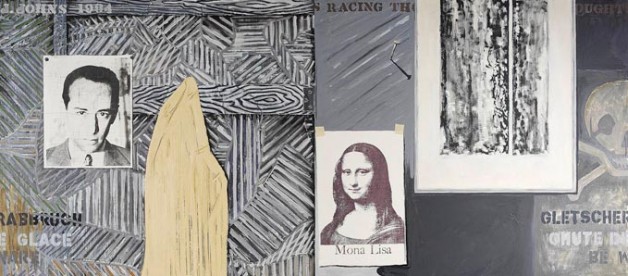

Image: Jasper Johns, Racing Thoughts, 1984