While scrupulous people like me like to know the rules so that we can keep up with them, saints know they fall short of their duties and ask for help and mercy. When God answers their prayers, they spill over with grace and light, filled by something more potent than they could have thought to ask for. They are the great stone reservoirs, which, previously filled with water, now brim with potent wine (Leah Libresco, Arriving at Amen).

Strolling along in the Parisian Jardin des Plantes, the young students found themselves reviewing their years of learning. These years, spent in the lecture halls and libraries of La Sorbonne, made Jacques and Raïssa the victims of the relativism of science and the skepticism of philosophers. Standing at the edge of modern philosophy’s abyss, they nevertheless decided to place a bold confidence in their existence. They dared to hope a meaning of life would reveal itself, and then deliver them from the senselessness of the world. Raïssa writes, “But if the experiment should not be successful, the solution would be suicide; suicide before the years had accumulated their dust, before our youthful strength was spent. We wanted to die by a free act if it were impossible to live according to the truth” (We have been Friends Together, 68). The young couple had just forged a suicide pact.

Spared the chains of bondage of eclecticism or positivism, Jacques and Raïssa opened to the inwardness of life. They were spared, blessedly, from the horror of their 1901 pact because of their ardent pursuit of truth. Jacques and Raïssa Maritain went on to discover the friendship of Leon Bloy, who introduced them, in turn, to friendship with Christ. In 1906, they were baptized Catholics, with members of la famille Bloy serving as their godparents. The Maritains’ journey to Catholic Christianity culminated in their realization that truth pursued them. By allowing themselves to fall into the trap of truth, they were set free.

Leah Libresco is another pilgrim of the absolute. Her zealous quest for truth cannot help but inspire and edify. Like the Maritains of twentieth-century France, Washington D.C.’s own twenty-first-century Libresco was stunned to find a God who loved her. Atheist-turned-Catholic blogger, Libresco notes the pivotal realization of her own conversion: “I guess morality just loves me or something.” Like that great servant of order and justice, Victor Hugo’s all-but-inimitable Inspector Javert, Libresco dedicated herself to uprightness and rectitude. Yet unlike Javert, Libresco found herself stopped in her tracks by the law of mercy: “If morality reached out to me, it had to be offering itself as a gift: it wanted good for me, not from me.”

Which brings us to Leah Libresco’s absolutely charming Arriving at Amen. How to sum up such a book? It’s a dance of course. It’s a quick-step, capturing the candor of a Virginia reel, yet lacking none of the grace of a waltz. Her book, like the best of dances, leaves the reader breathless and laughing–reveling in the sheer delight of its twists and turns.

The great strength of her presentation is that Libresco manages to show how our philosophical and theological prejudices show up in our prayer life. Few considerations could be more profoundly Christian. What we think about the world matters, and it matters most intimately in our personal life with God. Whether she’s debunking her Kantian-Stoic prejudice against petitionary prayer or her fascination with rubrics about the treatment of the Eucharist, by offering her own scruples and perspective, she affords the rest of us avenues of growth. Libresco’s book abounds with priceless examples, which are as accessible and welcome as they are intimate and creative.

Arriving at Amen chronicles the bizarre crossroads of contemporary American Catholicism. Ours is now a Church inspired by the fruitful models of Catholic bloggers’ own little examens, prayed with the iBreviary app, and where allegiance to saints is chosen by online generators (there’s as much determinism there as in the holy cards traded by happen-stance on playgrounds of yore, I suppose). If the spiritual classicals of perennial value appear to you hindered by the dust of centuries past, fear not, because Libresco’s book opens ancient devotions like lectio divina, the divine office, and the rosary with insight pregnant for our times: “The joyful mysteries, which begin with Mary’s great ‘Amen,’ invite me to make a small one, at any scale, to receive the chance to better know the God who is Love at all scales.”

Perhaps the best of what Libresco offers is her insatiable energy and enthusiasm. She moves, unexhausted, from exercise to exercise. This greatest virtue of modernity directly combats the sloth to which we lovers of the one, true, and good are too often prone. Urging us onward to grapple with prayer, she notes, “If I wait to offer prayers only in moments of peace and confidence, I’ll lose the chance to invite God into all parts of my life, including the tumultuous moments when I need him most.” Libresco eloquently details the challenges of prayer, and captures–with strokes only the most talented expressionist could paint–the essence of the landscape of the spiritual life.

Lifelong Catholics will cherish the opportunity to examine the overlooked and underappreciated with Libresco. She’s at her best chronicling confession: “When I lay aside sins and ask for the grace to go forth and sin no more, I am being more human than ever, for the common vocation of all humans is sainthood.” Converts will appreciate the rigor of her arguments and the companionship she offers along the way: “A Hail Mary seemed like a decent candidate for a mental circuit breaker that even an atheist like me could appreciate.” Arriving at Amen is precisely the kind of book to offer a friend or grandchild looking for something more out of their faith, which is perhaps the highest praise that can be said of Christian writing today! It gives its reader a pious, intellectually robust, and personal take on living the spiritual life, and deserves a home on every Catholic bookshelf or Kindle.

✠

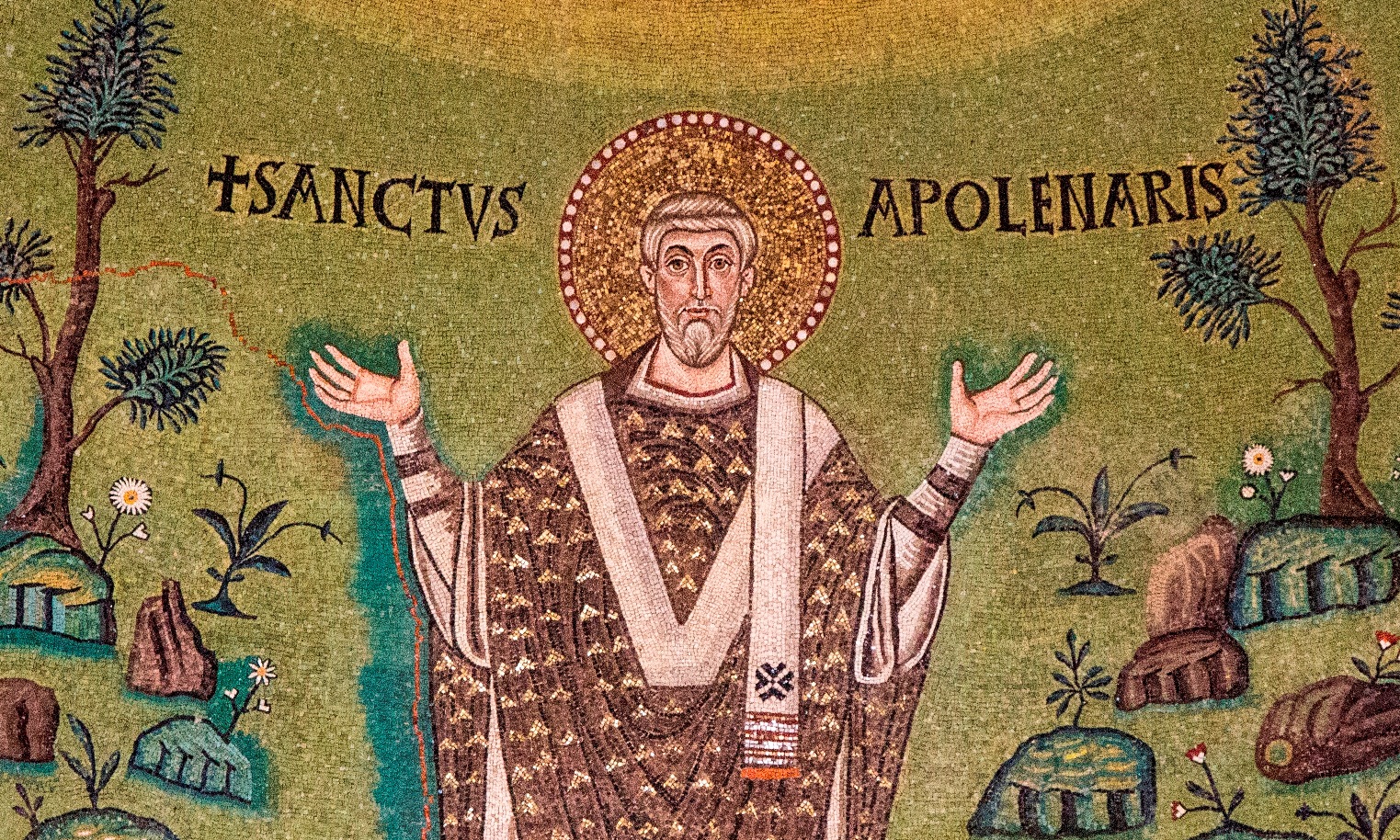

Image: Fr. Lawrence Lew, O.P., Saint Apollinaris of Ravenna