There’s an interesting feature about many artistic representations of the Ascension of Jesus into heaven, common to the works of both run-of-the-mill painters and masters like Rembrandt: namely, they are very boring.

Now I don’t want to blame the great masters and their lesser counterparts for phoning in their treatment of the subject; it’s just almost impossible to represent the Ascension in an artistically meaningful way. After all, at the Ascension the disciples witness Jesus pass from the visibility of his life on earth to the invisibility of his life in heaven, which is not really an event that tangible arts can represent easily.

Nor, to be honest, is the Ascension an event that we can easily wrap our minds around, even forgetting the question of art. After all, if the thirty-three years of Jesus’ earthly life and the forty days after his resurrection were able to plant the seeds of the Church and win the redemption of mankind, doesn’t it seem reasonable to expect that Jesus’ best move would have been to stick around visibly on earth, letting everyone see him resurrected, not aging as the ages pass, thus forcing all reasonable people to conclude that this immortal man must in fact be the Son of God? Wouldn’t a Jesus who reigned in his resurrected body on earth have won more souls to heaven, simply by the undeniability of his presence? To put it simply: isn’t the spiritual character of Christ’s Ascension the very obstacle that we physical beings stumble over and thus fall into unbelief?

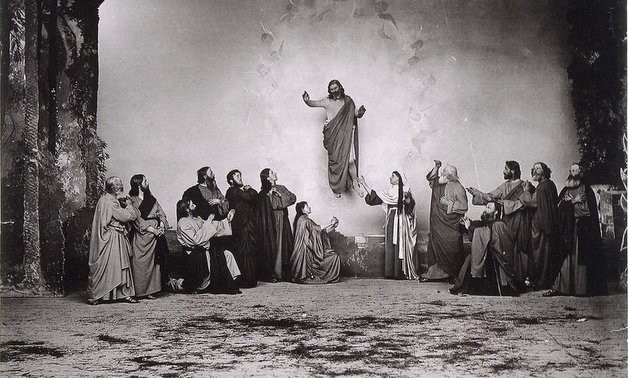

Happily, there’s a very strange artistic representation of the Ascension that solves the difficulties of the preceding paragraphs, by being both compositionally fascinating and theologically illuminating. It’s the image that appears as the featured image for this post: titled simply Ascension, it is a photograph produced by an unknown German in 1890, currently held by the Museum of Fine Arts in Boston.

Everything about this image is odd. First, it’s a photograph, which is fairly strange unless we accept that Bill and Ted’s Excellent Adventure was actually a documentary all along. Second, the actual composition of the scene is unusual: although the scriptural accounts specify that the only witnesses to the Ascension were the eleven disciples (Mt 28:16, cf. Acts 1:1-11), here we have Mary Magdalene and Mary the Mother of Jesus thrown in as well. So what’s going on here?

The image can reasonably be put into the pictorialist school of photography, which sought to compose photographs in the manner of a painting, rather than merely recording events that passed a camera’s lens. That is, the pictorialists sometimes—as in this photograph—sought to capture the uncapturable, to photograph the unphotographable, making visible what is invisible either by its nature or because it has passed in time. As a result, this idiosyncratic and short-lived art form was perhaps uniquely well-suited to represent the simultaneously fleshly and spiritual character of the Ascension, when Jesus’ resurrected humanity really went to heaven in his physical body, where he still reigns in perfect equality with the Father and the Spirit.

In this image, the spiritual reality of the Ascension is revealed in its full splendor precisely as visible; Jesus’ bristling, bushy beard won’t be denied, and neither will the bony leg that juts out from underneath his tunic, nearly making contact with Mary’s outstretched arm. Jesus’ humanity will not be denied here, even as it is being taken up into the ethereal realm of the painted whorl of cherubim on the backdrop wall. Moreover, the visible composition of the scene itself reveals the inner spiritual reality of the event, by the particular imposition of Mary Magdalene and Mary the Mother of Jesus. That is, with the insertion of those two figures, the artist creates a perfect echo with the crucifixion, where John (to Mary Magdalene’s left here) and the two Marys are often depicted in precisely these positions and poses. The additional presence of the remaining ten disciples from the Ascension scene conflates the two, signaling both the unity of Christ’s redemptive sacrifice on the Cross and the Ascension, as well as the particular instantiation of redemption in the lives of the apostles who had fled the earlier event. The visible, then, is the key to the invisible, just as the invisible is the key to the visible; neither makes sense without the other.

This is the inner dynamic of the Ascension, and of the very redemption of Christ. Jesus did not want to remain in his visible, risen humanity on earth forever, lest men and women forget that something more remains for us; he came not to make a permanent base out of the waystation of earth, but to lead us to the more perfect homeland of heaven, drawing us through his Incarnation to share in his divinity. With the incarnation, life, death, resurrection, and ascension of Jesus, the visible is now shot through with the glorious reality of heaven—where we will be in the closest spiritual presence to the invisible God—and we in turn are only drawn to that spiritual perfection in and through our bodily existence. We go to God not as angels, severed from our bodiliness, but as redeemed men and women, living a share in the life of heaven already on earth by grace. Christ’s ascension into heaven makes this reality known to us, as his reign in heaven makes his grace accessible to us.

So next time you find yourself in a muddle about the meaning of the Ascension, take a trip back in time with our nineteenth-century German friend, and let your eyes behold in faith the visibility of the invisible God.

✠

Image: Ascension