Salty. Now there’s a word that well describes fishermen. Along with it comes a string of supporting adjectives: Terse. Somber. Laconic. Matter-of-fact. Proud. Quiet.

Everyone’s familiar with the stereotype, whether you grew up in Baltimore, or simply were forced to read The Old Man and the Sea in high school. During college, I spent two summers working on salmon boats in Alaska. It’s true that fishermen are just these sorts of men. Sure, they know how to keep themselves sane on long hours with little sleep – telling stories, some hoot-n-holler, discussing the state of the union – but at the end of the day, they come to get a job done. Out on the water, there are exhilarating moments, hauling in a full net of fish, or graceful mornings trolling on a glassy surface and laying out lines in the early dawn. But these men don’t come up north just to breathe in clean air and get poetic. They’re there to catch fish and make money.

Last December I was on a flight sitting next to a tugboat captain. He was quiet and had a large beard, which the stewardess said reminded her of Zac Brown. I’m a talker, so we talked, and I asked him why he chose his profession. He replied very simply, “Well, my old man drove boats and showed me how… I’ve spent all my life in boats.” I was fishing for something like, “What kind of meaning do you find in your work?” He basically shrugged his shoulders and responded, “This is just my work. What else would I do?” It quickly occurred to me that those on the lookout for “deeper meaning” are often outside viewers, like journalists, or inquisitive neighbors prying for some material for their blog posts. Real working men, like our tugboat captain, simply work. They like it or don’t like it, but it’s their life.

I like to think of the early Simon Peter as one of these men, not looking too much into why Jesus wanted to go to the other side, but just gathering the men to make it happen: “Alright, the Master said we’re going to the other side, let’s load up and get rowing.” But God has a way of changing men, if they hang around him long enough. At first, Jesus embraces the facts of his friends’ lifestyle. They leave their nets, but then he borrows their boats: He preached from their boats (Lk 5:3), worked miracles (5:6), slept in boats (8:23), and escaped the crowds by boat (Mk 6:32). Why this method? Because they had the means, and it meant quicker travel between the villages of Galilee. Because water acts as a natural microphone in teaching the crowds. Jesus, too, can at times be simply practical.

Then right under their proud noses, within their familiar context, he begins to work something deeper. How exactly will he make fishermen into fishers of men? Simply by pushing their hard-earned skills past their breaking point. Let’s consider the Storm at Sea (Mt 8:23). They’re making a night passage, the boats are overwhelmed by waves, and Jesus is asleep in the stern. The disciples cry out for him, “Save, Lord!” But Jesus isn’t a fisherman. He’s spent his life carving wood and laying stone for houses. He doesn’t captain boats. They do. Here’s where these practical men in an entirely practical situation (i.e., “We’re drowning”) find themselves caught in the net of a life lesson: Right here in their area of expertise, these grown men fall to pieces. And only then do they finally start to piece together their need for the Lord. Before he would teach them, “Unless you become like little children,” they learned dependency in the boat with God.

Self-reliant. Now there’s a word that well describes all of us. Along with it comes a string of supporting adjectives: Stubborn. Limited. Insecure. Distracted. Cynical. Quixotic. Green.

Fishermen are really like all men: I’ve seen them attack each other, and I’ve seen them pray together; I’ve seen them cry in remembering the past, and laugh at cheap jokes. Some wander the docks patting backs, still trying to fit in with the guys, and I’ve seen others who are noble straight through, who have braved some mighty storms, standing steeled and firm behind the wheel. Yet despite our fluctuations, written in every man’s nature is this instinct for self-reliance. Challenges are around every corner, and we must protect and provide. We must take control. But life always has its ways of reminding us of our weaknesses, and no one is exempt from sooner or later facing their failures. That’s why fishermen, within an inch of their lives, call out to a carpenter: they know they need God, and God is with them. Then like the great myths of old, he rises from sleep and shouts at the storm until it turns to a whisper. They murmur among themselves, “What sort of man is this, that even wind and sea obey him?” It’s no great feat getting the winds to obey their Creator’s voice; getting men to listen from their hearts is a far greater difficulty, which often requires a touch of dramatics.

In the end, it seems likely that Jesus led them into this storm on purpose. The great saints have known that faith grows best in darkness. They have learned that God allows certain storms in our life, so we may cast ourselves on him more and more. That’s why a landlocked nun, frail and lacking all the virility of the apostles, could say to Jesus from her heaviest agony, “You may sleep in my boat, I will not wake you” (Therese of Lisieux, Poem 17).

✠

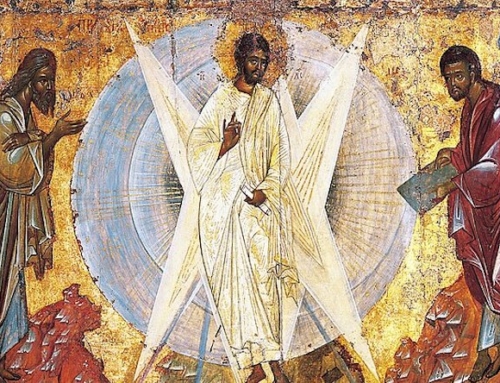

Image: Eugene Boudin, Rough Seas