Statistical data on why people get divorced is notoriously difficult to establish reliably. The man and the woman tend to report the cause of the divorce differently, many divorce filings force the couple to reduce all their problems to a single phrase (“just grew apart” being a favorite), and couples themselves don’t always have the keenest insight into what did and didn’t work in their marriage. That being said, we can point cautiously to three large areas that recent data indicate are major contributors to divorce: finances, Facebook, and pornography.

The first of these is obvious enough—money problems are always a source of tension, and it’s easy for especially young couples to believe that Love Will Conquer All and to avoid having serious talks about financial expectations before marriage. But the latter two are rather new: Facebook has only been emerging as a contributor to divorce in the last three years or so, and pornography roared out of near-obscurity in the mid-nineties to become a major factor in 56% of divorces back in 2002.

But perhaps this trilogy is no great surprise after all. Finances, Facebook, and pornography reduce to man’s three great disordered values: money, power, and sex; and these three in turn are merely the failed versions of the three true values that guide human life: faith, hope, and love.

Money issues become a problem in a marriage not just when one of the spouses turns out to be a Gordon Gekko-type monomaniac or an Imelda Marcos-type shoeaholic. Unresolved differences of opinion about how to coordinate individual and shared expenses, how much of the salary should go to housing, what should be sacrificed for children and what shouldn’t, what each spouse’s career goals should be, etc., can rapidly pile up and create terribly difficult situations. And these problems do not always arise from malice; misunderstanding, miscommunication, and lack of knowledge about how to fix the situation are more likely culprits.

All these money woes relate in a certain way to faith. Even on the natural level, a man has to make acts of faith in order to trust that he can make plans that will bear meaningfully on the future, that he and his spouse can resolve their differences over time, and that they can live with uncertainty. But struggles with money often involve just this refusal to accept uncertainty: we try to amass more and more money to prepare for every eventuality, or we throw away all our money as soon as we have it to make ourselves feel better now, come what may later. Natural acts of faith and trust in one’s spouse make more room for honest discourse, and for gradual change; add to that the supernatural faith in God that enlivens the sacrament of marriage, and it becomes easier—although still a matter of long, hard labor—to rise above the power of Mammon.

As for Facebook and other social media tools, they are not intrinsically problematic. Posting a photograph of a meal I just made (or a link to an article I just wrote) might tend toward the self-indulgent, but are not grave moral issues. Facebook becomes a problem when it replaces real human interactions, when I spend more time seeing to the care and upkeep of my and others’ online personas than to the relationships right in front of me. Spending three seconds liking a comment from an old high-school flame may be harmless—unless my wife is trying to talk to me at the same time.

But still we might ask: Why does obsessive status-updating and photo-sharing tempt me against the hope needed to sustain a healthy marriage? The answer lies in the relation between Facebook and control. Facebook is most dangerous when it becomes a simulacrum of real experience, a life like mine only pruned and made perfect, with only my wittiest thoughts broadcast to the world, and only my most exciting events documented. Between spouses it can become a source of jealousy and amateur spy-work, desperately trying to piece together every minute of the other spouse’s day. All this stems from a refusal to hope, to look to a good beyond what I already possess. Hope of its nature involves looking confidently towards a good that is beyond me yet can draw me into itself; it is the confidence of renouncing control, recognizing that I do not have to force my life to be perfect by my own power. A relationship built on hope can transcend the ready-made categories of likes, dislikes, comments, and shares, and can grow through both hardship and joy, confident that the strength to endure and mature is a gift from outside myself, not a function of my power.

Lastly, we have pornography. In the age of ubiquitous Wi-Fi Internet and portable devices, we should hardly be surprised at the skyrocketing rates of pornography addiction and their corollary effects on marriage. Here, the good at question, sex, is entirely inverted and turned against itself, corroding spouses’ ability to associate sex and respect, pleasure and humanity.

The fact that pornography is a corruption of love comes as no surprise, but here I am not meaning “love” in a merely euphemistic sense: pornography is an abandonment of love in its fullest sense, a rejection of the idea that a man can open himself up to another, who in turn opens herself to him. Love is this turning-toward, being shaped by what is seen, and willing the good for the other so deeply that my awareness of my own good is united in the other’s. This love is the truly liberating love made possible by the permanence, fruitfulness, and exclusivity of the sacrament of marriage.

Conflict-ridden finances, obsessive use of Facebook, and pornography may be all around us, but they do not have the final word on the sacrament of marriage in general, or on any individual marriage. Faith, hope, and love are the core of man’s personal relationship with God, and as such pour forth into his relationships with other men, enlivened by His grace. The grace that God gives couples in the sacrament of marriage, buoying healthy natural practices of honesty, abdication of control, and respectful sexuality, can heal even the deepest wounds, and can build foundations for a life of marital labor in faith, hope, and love.

✠

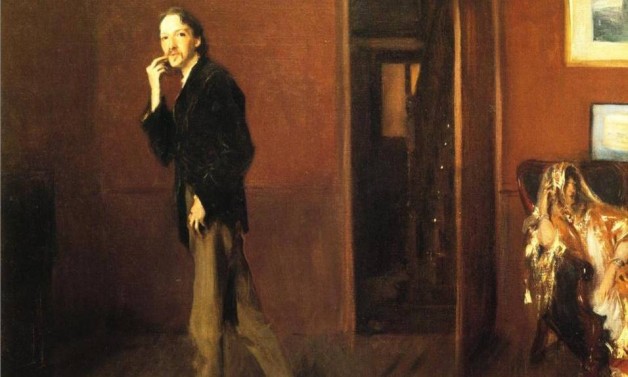

Image: John Singer Sargent, Robert Louis Stevenson and his wife