When asked in what way Christianity is related to violence, most believers would probably say they are mutually exclusive. The notion of violence seems utterly repugnant to the Christ who spoke such tender words as “Blessed are the meek” and “Blessed are the peacemakers” from the Mount of the Beatitudes.

This conviction is confirmed as we watch the great destruction wrought by religiously motivated violence throughout the world. Even the Church sometimes shies away from language that carries violent connotations. Just one example is the dwindling number of allusions to the Church Militant (a reference to the Church on earth, as distinguished from the Church Suffering and the Church Glorified). And yet, the words of Christ on the matter are very clear: “[T]he kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and men of violence take it by force” (Matt 11:12).

What then are we to make of this passage?

In offering one potential solution, we can look to Dante’s Divine Comedy. In the second canto of the Purgatorio, Dante and Virgil have arrived on the shore of the mount of Purgatory. From across the water, they see a vessel filled with souls being conducted across the water by an angel boatman. After the souls have disembarked, one among them, Casella, recognizes his friend Dante and the two have a happy reunion:

And one I saw advance, all eagerness

To clasp me in its arms, whose looks expressed

Such love as moved me to a like embrace.

Within a few lines, Dante asks Casella to sing, whereupon Casella begins at once to sing a poem of Dante’s. In a few lines of verse, Dante describes its delightful effect. But no sooner has the music begun than the convivial poem is broken off by the intervention of Cato of Utica, the guardian of the shore of Purgatory:

How now, you laggard souls! what’s this?

Why all this dawdling? why this negligence?

Run to the mountains, slough away the filth

That will not let you see God’s countenance.

To this stern rebuke, Dante, Virgil, and the newly arrived souls react promptly, and the canto ends with them scurrying up the mount into ante-purgatory.

One must wonder why this beautiful moment of friendship, music, and companionship had to be cut short and with such violence. The answer becomes clear in light of the ultimate purpose for which all of these individuals have come. This is the Mount of Purgatory; at its summit is the earthly paradise and the promise of heavenly beatitude. All things must be ordered to that end; if not, then they amount to mere distractions. Thus, in light of the inestimable goodness of their end, these distractions must be dealt with violently. “The kingdom of heaven suffers violence, and violent men take it by force.”

It seems, then, that the violence demanded of every Christian is a violence of the heart, or as it is called in the tradition, asceticism. Mindful of the dignity given him by the ultimate end to which he is ordained, the Christian is asked to order all things to his heavenly destiny. This means, moreover, that he is called to violently recast his life along the lines of the Gospel and thereby to blot out the incongruities and contradictions that impede this high calling. What this looks like differs somewhat for each individual, but by grace it’s possible … at least Dante seems to think so.

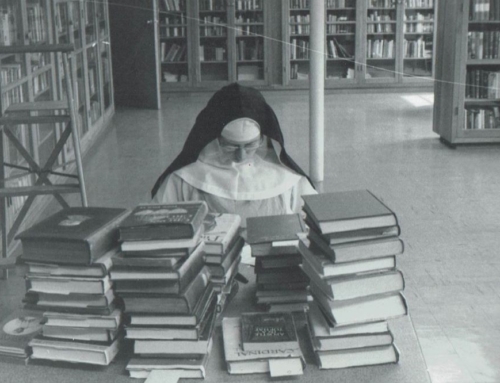

Image: Gustave Dore, Celestial Helmsman