It is easy to think of St. Peter Claver, S.J., the “slave of blacks forever,” as a proto-humanitarian. Born in Spain in 1581, he entered the Society of Jesus at the age of twenty. After training to evangelize the people of New Spain he landed in Cartagena, Colombia, where he would spend the next forty-plus years giving succor to slaves arriving on those hellish ships. In the Office of Readings, we read a letter from the saint in which he gives an example of his work:

There were two blacks, nearer death than life, already cold, whose pulse could scarcely be detected. With the help of a tile we pulled some live coals together and placed them in the middle near the dying men. Into this fire we tossed aromatics. Of these we had two wallets full, and we used them all up on this occasion. Then, using our own cloaks, for they had nothing of this sort, and to ask the owners for others would have been a waste of words, we provided for them a smoke treatment, by which they seemed to recover their warmth and the breath of life. The joy in their eyes as they looked at us was something to see.

This moving account shows St. Peter Claver to be a true humanitarian by anyone’s standards. But this is not the important part of the letter for St. Peter Claver. He goes on:

After this we began an elementary instruction about baptism, that is, the wonderful effects of the sacrament on body and soul. When by their answers to our questions they showed that they had sufficiently understood this, we went on to a more extensive instruction, namely, about the one God, who rewards and punishes each one according to his merit, and the rest. We asked them to make an act of contrition and to manifest their detestation of their sins. Finally, when they appeared sufficiently prepared, we declared to them the mysteries of the Trinity, the Incarnation and the Passion. Showing them Christ fastened to the cross, as he is depicted on the baptismal font on which streams of blood flow down from his wounds, we led them in reciting an act of contrition in their own language.

In this enlightened age of ours, many would surely dismiss this aspect of St. Peter’s efforts as proof that he was still part of the structure of European imperialism, with its intolerant legacy of proselytizing. After all, today the religious aspect of ministry often takes a back seat to the more universal, inclusive message of human rights. The contemporary consensus seems to say, “If only Peter Claver had the benefit of a modern, liberal education, he would see the greater importance of broad-based humanitarianism compared with religious evangelization.”

But I don’t think he would, because the humanitarian element of his work—what we traditionally call the corporal works of mercy—go hand in hand with the spiritual works of mercy. When St. Peter Claver looked at the black men, women, and children, being rolled out of densely packed slave ships, he didn’t see mere humans: he saw men made in the image of God. St. Peter Claver wasn’t merely interested in making them more human, he was concerned with making them more divine.

St. Thomas Aquinas clarifies how to see the image of God in relation to man. Following Aristotle, he describes man as a rational animal. Being rational for St. Thomas meant being spiritual, having powers of intellect and will that transcend the purely physical. It meant being made in the image and likeness of God. That image and likeness does not only relate to God sharing in some way His divine nature, but even (to a certain extent) God as Triune. Consider St. Thomas in his Summa Theologiae:

Wherefore it is manifest that the distinction of the Divine Persons is suitable to the Divine Nature; and therefore to be to the image of God by imitation of the Divine Nature does not exclude being to the same image by the representation of the Divine Persons: but rather one follows from the other. We must, therefore, say that in man there exists the image of God, both as regards the Divine Nature and as regards the Trinity of Persons; for also in God Himself there is one Nature in Three Persons. (I, 93, 5)

When St. Thomas speaks of man, he speaks of a creature who is created in the image of the Triune God, and who is seeking to intensify and perfect this image in conformity with the only perfect and true Image, Jesus Christ. This intensification and perfection is found through the sacramental life, the means by which we are drawn into union with the very life of the Triune God.

St. Peter Claver saw the same reality. He saw not only physical suffering in these men and women, but a spiritual brokenness that comes from being separated from union with God.

In his essay, “The Weight of Glory,” C. S. Lewis expressed this insight well:

There are no ordinary people. You have never talked to a mere mortal. Nations, cultures, arts, civilizations—these are mortal, and their life is to ours as the life of a gnat. But it is immortals whom we joke with, work with, marry, snub, and exploit—immortal horrors or everlasting splendors.

St. Peter Claver was indeed a true humanitarian. He saw that our humanity is fulfilled and perfected by friendship with God. That way, he who made us in his image conforms us ever more closely to his divinity.

✠

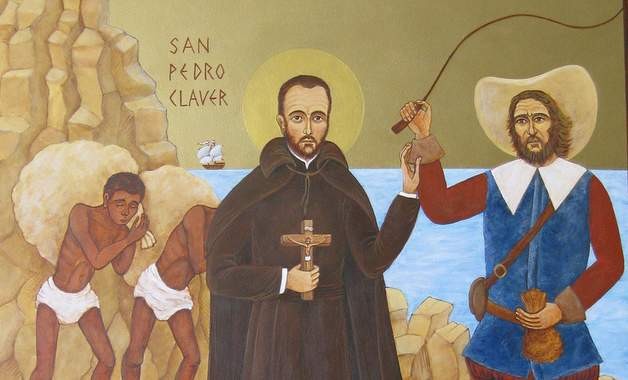

Image: Francisca Leighton, San Pedro Claver